THE scars and memories of World War II continue to haunt us in varying ways.

Whether it was the persecution of the Jewish people (referred to as the Holocaust) and Japanese internment, the loss of lives in the many battlegrounds (Normandy, Midway, Bataan, to name a few), the razing of many cities by invading forces, or the dropping of the atom bomb in Hiroshima in 1945, movies, specials, documentaries and television programs remind us of the horrors of war and the shattered pieces of their lives that people have had to form together in order to survive.

Yet, one of the darkest and haunting secrets of the Japanese occupation of the Philippines has been given little air time compared to the many atrocities committed by the Nazi and Imperial Japanese Army — and that is the experience of the numerous comfort women in many nations where the Japanese occupied during World War II.

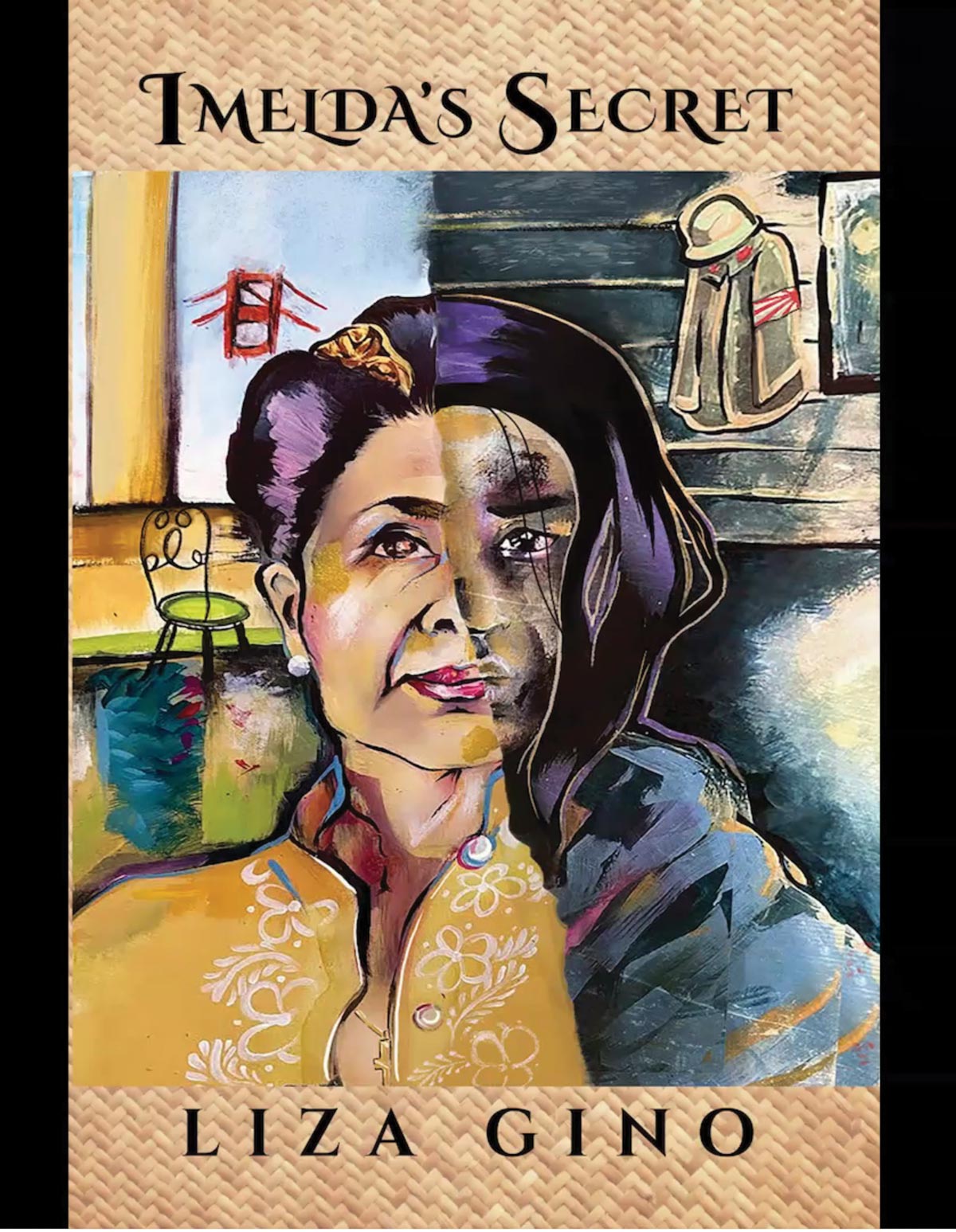

This is tackled in Liza Gino’s “Imelda’s Secret,” a book that tells the story of two cousins, Gloria and Imelda, who were comfort women during the Japanese occupation. While one (Gloria) reveals her past which opens her up to ostracization from family members and society, the other (Imelda) keeps her experience bottled up to protect herself and her family from ridicule. Gloria’s illness is a tipping point for Imelda as she becomes conflicted on whether to acknowledge publicly her experience as a comfort woman or to keep the status quo.

Comfort women were women and girls who were forced to work as sex slaves in brothels by the Imperial Japanese Army in areas they occupied during World War II. The brothels were said to be provided for Japanese soldiers to decrease the incidence of wartime rape, which caused anti-Japanese sentiment in occupied territories. Many young women were abducted from their homes for this purpose, or were recruited through false advertising by unscrupulous middlemen and wartime propaganda advocated by the Japanese regime in place. In many ways, experts say the comfort women experience parallels the human trafficking trade that exists today in many parts of the world.

An organized web event in late 2020 served as the book launch. Gino described her novel as a weaving of stories into a cohesive narrative based on true accounts from family and friends about the Japanese occupation in the Philippines.

“I could have written a novel just about World War II,” Gino said. “But I chose to bring it forward 40 years after the war. Even though it has been four decades after the liberation women are still struggling: women can’t tell their families, their loved ones because if they do, for some it’s very traumatic.”

Gino noted that she wrote “Imelda’s Secret” to give life to the silent warriors of World War II who have been discarded from history.

“The comfort woman story is only in the oral story, it is not written down. And all attempts to write it down has been hindered. We need to acknowledge and honor these women, and we also all need to make sure that we know about it and that we stop this from ever happening again,” the University of the Philippines alumna said, while adding that women activists have been instrumental in making the comfort women issue become public.

The author said that the story is set in San Francisco because she feels that “this is the only place where you can actually have this kind of conversation where it’s face-to-face — what you feel and what you’ve gone through — and hope that someone will catch you and say, ‘It’s okay. We still love you. We still want you.’”

Gino added that having these kinds of conversations and opening up, as the book’s storyline shows, is how one can “unhook, unchain and anchor yourself because keeping a secret for 40 years-plus can be damaging to the psyche. And that’s why Imelda’s secret should no longer be a secret.”

For the author, the surviving comfort women of today are still doing their own version of the Bataan Death March every day and it is up to society to illuminate their plight and advocate for women’s issues in general.

“We should get them justice and make people aware that this happened… we need to find them justice,” Gino stated.

Image capture from book launch

Collaborators for ‘Imelda’s Secret’

The online book launch introduced the many collaborators that helped Gino make the book a reality.

Longtime Filipino American community leader and philanthropist Dr. Yolanda Ortega Stearn allowed her image to be used as the canvas for the artwork that is featured as the book cover executed by artist Angeli Clarisse Lata.

“I think we all have a moral duty and obligation to write the story, to document the stories, to remind every generation that we are raising [about trafficked women],” Stearn said. “I am really happy to see this movement because what we started in Berkeley during the women’s liberation movement and all these movements in experimental schools brought out the story of the comfort women in the Japanese concentration camps, and all these unpleasant things that occurred that people simply did not want to talk about.”

“It was really difficult even then to get women to come out and tell their story because there was such a stigma. And there was the shame that they felt to be part of this. This book that Liza has written really, really clears a smooth passage for all the women who have been abused or who have been trafficked. And trafficking is continuing today. It clears a passage so that it gives them strength and the courage to speak up,” Stearn added, while wishing that today’s younger generation will up the book and take up the cudgels for victims of human trafficking.

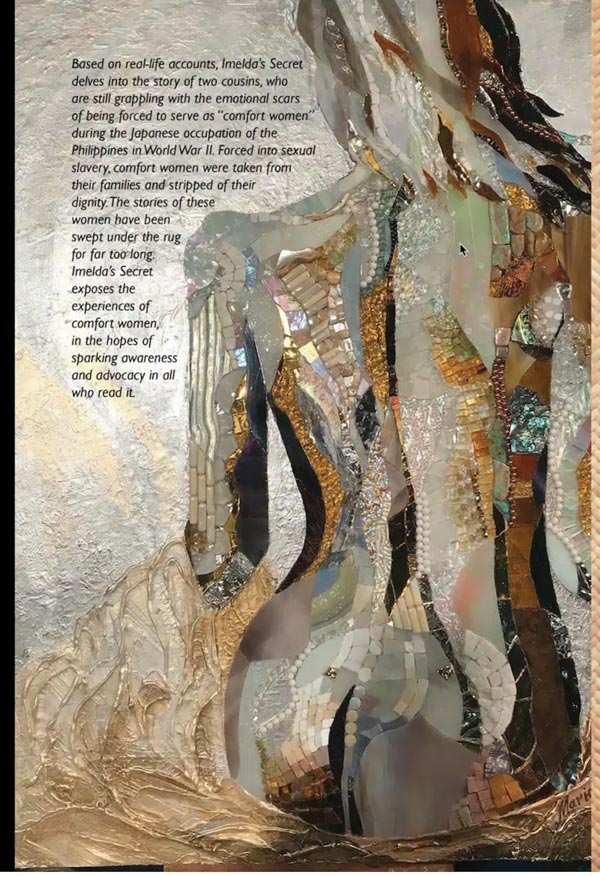

Former Binibining Pilipinas Universe winner Maria Isobel Lopez, a University of the Philippines graduate herself, created a mixed mosaic glass artwork for the book’s back cover. Liza was one of the runners-up the year that Lopez took the crown.

According to Lopez, who has a Fine Arts degree, she was inspired to do the Illuminati Tree, subtitled Imelda’s Secret, when Gino informed her about the book about two years ago. While the word illuminati refers to a secret society since the 1700s, Lopez said her artwork title refers to the “enlightened ones, the comfort women in the book which hopes to bring clarity, truth and understanding to these women.”

The woman’s figure in the mosaic depicts how a person tries to deflect confrontation or wants to forget something, and this is by turning their back, Lopez explained.

“I used mixed glass media made up of man-made and natural stones. And you know very well that glass is a difficult medium to handle… it’s very hard to control, not to mention the danger that the glass can go into your eyes,” Maria Isobel said, while adding that in making the mosaic, some of the pieces cut her fingers so part of her DNA is embedded in the artwork.

“I look forward to the journey of ‘Imelda’s Secret’ and I would like to congratulate my good friend Liza Gino for coming up with this very worthwhile book,” Lopez said. “We cannot forget these things… even if World War II is over the lessons that we learned and the things that are happening in the world [have] not stopped.”

Film and television composer Roger Neill, for his part, presented a short sample of the haunting score he developed for “Imelda’s Secret.” Neill’s credits include scores for films like “29th Century Women,” “Don’t Think Twice” and “The Beginners,” as well as for television shows “Mozart In The Jungle” and “King of the Hill.”

Neill described the music he created as beginning with an epic sweep, romantic, but also poignant and tragic, which then transitions into something quiet and contemplative, and then ends with kind of a question mark. He added that the score he ended up with was what he had initially imagined and conceptualized for “Imelda’s Secret.”

Women activists for comfort women

Also joining the launch were women activists Judith Mirkinson, Miho Lee and Sharon Cabusao Silva, as well as “Lola Isang,” who shared a short video message.

Mirkinson and Lee, who are members of the San Francisco Comfort Women Justice Coalition, were contacted by the author to contribute to the book, with “the purpose of lending clarity on why this issue is relevant and making the connection with the reality we are living every day, wherever we may be.”

Lee shared that many women’s groups — around 20 — ultimately coalesced to create a memorial dedicated to comfort women in San Francisco (located near St. Mary’s Square, at the crossroads of Chinatown and the Financial District; the statue shows a Filipino, Korean and Chinese woman) after learning of a group of Japanese government-backed right-wing historical denialists who were organizing in the Bay Area and other places in the United States to “educate the public that comfort women stories are complete fabrication.”

Lee, who teaches at San Francisco State University, added that the power of bringing the narrative of comfort women stories, as told by the survivors themselves, brings two added components – that of healing and power/subversion.

“We, as next generation, and our next generation are really the vessels through which that healing can happen. This is a multi-generational effort that we are a part of. This is not a thing that happened in the past that we are disconnected [from]. We are living the reality of bringing the healing as an act of empowerment,” Lee explained in reference to how comfort women have yet to heal from their wounds seeing as how their stories have remained buried or were silenced by society.

Lee continued: “This is also an act of subversion… As we speak, currently the Japanese government is doing a lot of things within its power to rewrite this history… The fact that these stories are being preserved and told and personalized on the women’s own terms, from their perspective, is helping counter the intentional erasure.”

Mirkinson, for her part, said while they want the Japanese government to officially apologize for the atrocities committed against these women, people should also look beyond what they see as victimhood and see how comfort women coming out from the shadows gave power and voice to women around the world which helped change international law.

“For the first time in history, women are now actually considered under international law human beings, and violence and rape against women are considered as a form of torture.

And the history of the comfort women is a part of that, so that is why we consider this part of history as essential,” Mirkinson explained.

Liga Filipina’s Cabusao Silva, meanwhile, shared that the plight of comfort women is still a burning issue today. Of about a thousand women who came forward to talk about their experiences as comfort women, the Gabriela-run organization, she said, could only document about 175 cases due to lack of funding and manpower. Only about 12 to 13 of these 175 women are still alive, and just four of these remaining women are strong enough to attend events.

“Many of them still have the fire in their hearts,” Cabusao Silva revealed. “They would be willing to come out in the streets to tell their stories and to tell Japan, to demand the justice that they have long been demanding from the Japanese government.”

Although they would like to have a more dynamic movement that continues the call for justice, compensation for the victims and for historical inclusion, the current political situation in the Philippines and the lack of awareness from the younger generation means they will have to educate young people about the issue of comfort women and, in a general way, about military sexual violence that continues to plague different parts around the world.

In a brief video message, Lola Isang (Narcisa Claveria) thanked Liza for writing her novel and said, “Itong laban na ito, hinding-hindi ako susuko… tuloy lang ang laban. Thanks sa suporta niya sa laban ng mga lola. Hinding-hindi ko makakalimutan ‘yung pagpapasalamat sa kanila kasi sila rin ‘yung tumutulong, sumusuporta sa laban ng mga lola kasi ang gobyernong Hapon ay hindi naman kami pinapakinggan. Mula noon hanggang ngayon, wala pa kaming nakamit na tunay na [inaudible].”

This early, the novel has already garnered a couple of awards – a Pinnacle Book Achievement Award for the women’s interest category, and first place for Historical Fiction at the Royal Dragonfly Book Awards. There are also plans to turn the book into a movie, with a script in the works.

“Imelda’s Secret” is available at www.imeldassecret.com in book form or as an e-book. Connect with author Liza Gino at [email protected].