SINCE March, 74 health care workers of Filipino ancestry have died of COVID-19 in the United States. The number is nearly double the fatalities of individuals working in the same sector back in the Philippines.

In the United Kingdom, where around 20,000 Filipinos are employed in the national health care system, 41 deaths have been reported.

Despite the rate at which Filipino health care workers have been dying on the global front lines of the pandemic, there is no centralized place for tracking this data for Filipinos beyond separate sources that include news articles, online obituaries, fundraising pages and social media posts.

A new digital project housed on Kanlungan.net — the Filipino word for shelter and resting place — was unveiled this week by transnational feminist organization AF3IRM, which seeks to memorialize all the health care worker deaths of Filipinos in and out of the Philippines.

“Kanlungan has this tenderness to it. It’s a cradle, it’s where you are held,” Ninotchka Rosca, the organization’s co-founder, told the Asian Journal. “It’s a very good word to convey the idea that we maintain a home in these memories.”

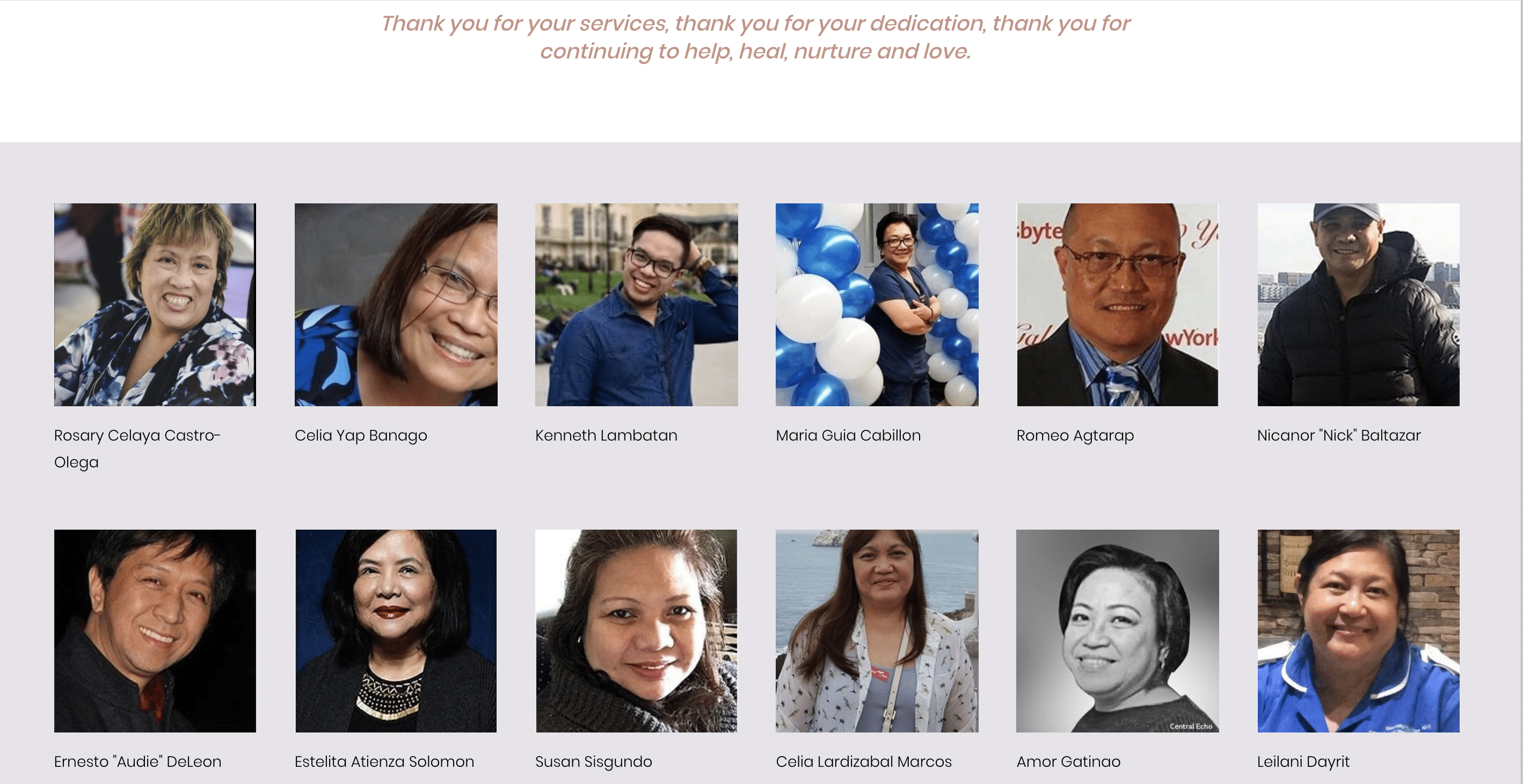

The website, made by a small volunteer team of activists, data analysts, artists and writers over the course of five weeks, contains a digital memorial wall highlighting the names and photos of the fallen workers.

“We took so much time to choose the photos and it reminded me of the process of the funeral rights of our family members where you try to choose a photo they like of themselves, a photo that shows them in their joy,” Jollene Levid, a union organizer and member of AF3IRM’s transnational committee which spearheaded the project, told the Asian Journal.

The information was pulled from at least two public sources, such as news sites or GoFundMe pages, that confirmed the passing and the individual’s Filipino ancestry. Social media accounts have also provided an added layer of confirmation. However, the team has been cautious to not assume ethnicity solely based on last name or physical appearance.

“There are actually several names that are not on the list because we couldn’t verify whether or not they’re Filipino,” Levid said.

Levid recalled how in late March, she lost two family friends who worked as nurses alongside her mother for 20 years at a hospital in Los Angeles. Yet, their names hadn’t been released or honored widely.

She reached out to Rosca and aired frustrations about the lack of data, while Rosca offered the idea of a memorial, similar to a living altar. The ideas then spun into the website.

“We had a discussion about the fact that our family members are dying around the world to COVID-19, particularly those in the health care sector,” Levid said. “So it becomes not just a personal issue, but also a workers’ right issue, an immigration issue, and a dignity issue.”

The Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs provides daily updates on the number of overseas Filipinos who have been infected or have died, but does not provide further detail in terms of age, gender or occupation. To date, it has reported 340 deaths globally.

Meanwhile, the Philippine Embassy in Washington in mid-May reported 137 Filipinos have died since the virus outbreak hit the U.S., and said 40 were health care workers.

However, new evidence shows that the number of deaths among Filipinos employed in the U.S. health care system is nearly double that.

A global map on the Kanlungan website bears symbols marking where the deaths took place. By clicking each one, a visitor can see the individual’s name, location, profession and a link to a news article or obituary.

A graph also tallies the total number of known deaths by country: the United States (74 deaths), United Kingdom (41 deaths), the Philippines (33 deaths), United Arab Emirates (4 deaths), Canada (3 deaths), Bahamas (1 death) and Kuwait (1 death).

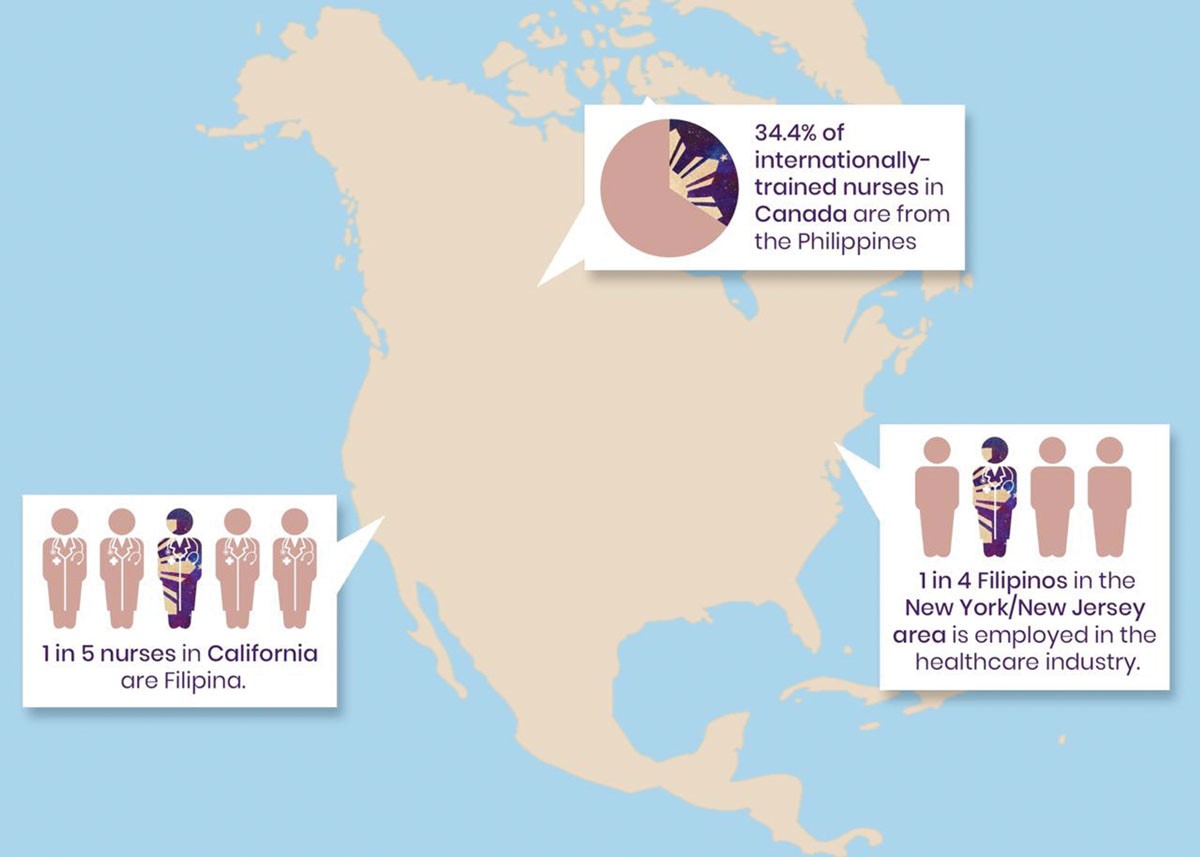

In the U.S., for example, the map shows that a large cluster of deaths occurred in the tri-state region, as 1 in 4 Filipinos in the New York and New Jersey area is employed in the health care sector.

The nurses who have perished included Maria Guia Cabillon, head nurse of Kings County Hospital emergency department in Brooklyn, New York, and Imelda Tangonan, who worked at Blythedale Children’s Hospital in Valhalla, New York.

But the fallen Filipinos are not only nurses. Deceased individuals include physicians, such as Dr. Tomas Pattugalan, 70, a primary care physician in Queens, New York; Dr. Alejandro Albano, 74, a doctor at Clove Lakes Healthcare and Rehabilitation in Staten Island, NY; Dr. Jessie Ariel Ferreras, 62, of New Jersey; and Dr. Leo Dela Cruz, 57, a geriatric psychiatrist at CarePoint Health in Jersey City, New Jersey. Or they held other positions at care facilities, such as Louis Torres, director of food services at a nursing home in Woodside, Queens and Lemuel Sison, a medical laboratory scientist who lived in Fresh Meadows, New York.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics started releasing the percentages of infections and deaths by race but only goes as far as clumping Asian groups together. Of the reported COVID-19 deaths nationwide, 5.4% are Asian.

In California — where nearly one-fifth of its registered nurse workforce is Filipino — the Department of Public Health also aggregates the data, finding 14.8% of the total deaths are among Asians, which comprise 15.4% of the total state population. The LA County Department of Public Health has the racial data available for 2,112 deaths and reported 17% are individuals of Asian descent.

Going deeper into LA County’s numbers, however, 30 COVID-19 related deaths have been among health care workers — 74% in skilled nursing facility staff and 52% nurses — as of May 21.

“We know those numbers must be Pinays,” Levid said.

Among the county’s known deaths are Rosary Castro-Olega, the first health care worker in the region taken by the disease; Emily Gualberto Canonizado of Oxnard who spent 31 years as a nurse; Anabelle Soriano Lustina, an RN from Carson; Celia Lardizabal Marcos, who was only equipped with a surgical mask when she responded to a patient suspected to have COVID-19 at CHA-Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center; and Arlene Aquino, a single mom and nurse who died on May 24.

“Data, anything from statistics to budgets, are not just political documents. They’re moral documents. What we’re seeing here in the United States, for example, is an unprecedented closure of hospital units and the displacement of health care workers who are already risking their lives every day to treat potentially positive COVID-19 patients,” Levid said.

As the health care profession has become part of the Filipino migration story, as well as a career route for multi-generations of many families, the AF3IRM team noted that Filipinos moving abroad to deliver care and risk their lives is not a new phenomenon under COVID-19.

However, decades later, higher-paying jobs overseas as well as a global demand for workers continue to fuel the Philippines as the largest exporter of nurses and other positions.

“It’s both a global and national issue. If we’re going to change the situation, we have to go to the root of the problem of migration,” Rosca said. “There’s such a disparity in the recognition of the essential skills of health care work. That cannot happen unless medical workers in the Philippines themselves get organized and push.”

Based on available sources that highlight the circumstances surrounding the worker’s death, several patterns have emerged, including: the disproportionate rate at which nurses have died at non-unionized facilities in the U.S.; higher mortality rates for those employed in long-term care facilities in Canada and the United Kingdom; and in the Philippines, the majority of fatalities have been among doctors.

Another trend, Rosca noted, is the correlation between a country’s number of deaths and how its government acted and responded upon the onset of COVID-19.

“With Boris Johnson in the UK and the high rate of deaths among Filipinos, it’s directly due to his unpreparedness and dismissal of the virus,” Rosca said. “Of course, that was until he got it. The irony is that the Filipino nurse who ended up in the same ward as him died.”

The group envisions the website as a resource for journalists, educators and activists to help with news reporting or advocating for workers, whether it’s for adequate personal protective equipment, better working conditions, fair wages, or more transparent contracts before Filipinos migrate abroad for work.

“How are we supposed to demand justice and talk about egregious working conditions when they’re not even naming our dead? Without data, your campaign will only go so far,” Levid said. “This data can be weaponized in a way that any data is weaponized, or in the way that Trump uses data against us every single day.”

On the website, individuals are encouraged to submit information about a deceased loved one or colleague along with a photo and fond memory.

“You don’t have to identify yourself so that you can remain anonymous if you choose to. But if you have a colleague, if you have a cousin, if you have someone else that has died and their employer refuses to release their name, this is a place where you can go so that your loved one can be rightfully named and honored,” Levid said.

**

Editor’s note: The Asian Journal is working to document those of Filipino descent who have lost their lives because of the coronavirus in the United States. If you know of someone or would like to offer a remembrance of someone who has died of COVID-19, please tell us about them by emailing digital@asianjournalinc.com with the subject line “Remembering Lives Lost.”