As protests continue across the United States for a second straight week, families are finding themselves having uncomfortable, yet crucial conversations about race, injustice and police brutality.

For many multicultural Filipino American families, these discussions are not new, but the latest events have renewed the national discourse and awareness around the systemic issues that disproportionately affect black Americans.

In her book “Raising Multicultural Children: Tools for Nurturing Identity in a Racialized World,” Farzana Nayani, a Filipina-Pakistani diversity, equity and inclusion specialist, made an argument for normalizing multiraciality and talking about race in a positive, nonstigmatized manner.

However, she recommended approaching the conversations holistically and with historical context to prevent children from gathering stereotypes or incomplete depictions of race from external influences.

“Conversations about race without talking about systemic inequity present an incomplete picture of reality and can do harm because they can leave children unprepared when facing challenges or new awareness to societal issues. It is important to teach our children and others around us how generations of systemic oppression and current unconscious bias, negative stereotyping, and explicit discrimination can and do happen due to race,” Nayani wrote.

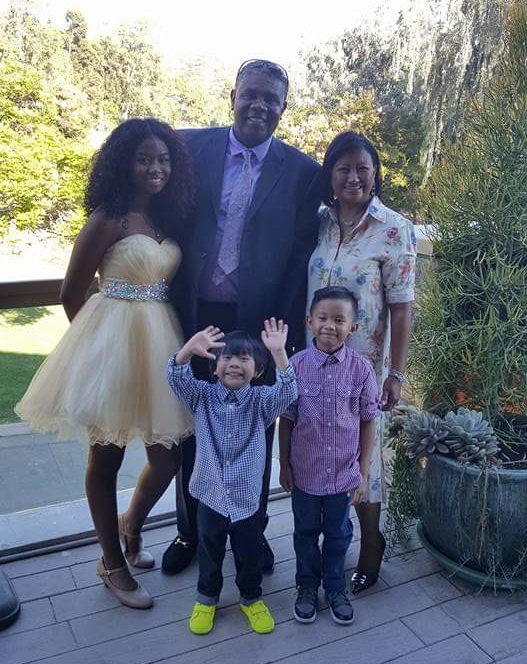

For Jennifer Taylor, a mother of two daughters ages 22 and 19 and one 17-year-old son in Arcadia, California, the self-education on raising a biracial family began as early as when she was pregnant with her first child to anticipate future questions and curiosity about being both Filipino and black. Through the years, she and her husband have been candid and truthful about American society’s treatment towards black Americans.

“I have been reading books on interracial and multicultural parenting since I was pregnant with my first child so I knew that the conversation about colorism and their mixed identity had to happen at a young age,” Taylor told the Asian Journal. “My husband and I have always been open in conversations and not sheltering the kids from the harsh reality of anti-blackness. There’s no need to candy coat hate.”

One particular book Taylor found helpful to read to her children is “I’m Chocolate, You’re Vanilla: Raising Healthy Black and Biracial Children in a Race Conscious World” by Marguerite Wright. Reaching out to friends and family members who are black has also helped through the years and inspired her and her daughters to start Swirls for Girls, a non-profit organization for multicultural girls and their caregivers in the Los Angeles area.

Monica Alvarez-Mitchell, a mother of four between the ages of 22 to 14 in the New York area, said the awareness of race began around the age of five when her eldest son was in school and a classmate called him black. Experts say the start of schooling is around the time when children begin to ask questions about the differences they perceive in others.

“My son didn’t know that he was black because his skin was light. So it became important that we explained why he was being called black. My son was confused about skin color versus culture,” Alvarez-Mitchell told the Asian Journal. “We had to explain that cultures define identity and that being black and Filipino was pretty special because we had two cultures to call our own. Despite what anyone says or how they say it, be proud because we were not only equal but in some ways even luckier than others.”

Jennifer Fontanilla, a mom in La Palma, California, similarly said that at the age of 4, her son began asking why his father has a darker skin tone. Other conversations have come along the way as her son, who is now 9 years old, is more becoming more perceptive of the world around him.

“I had to explain that there are different cultures and races and that that is ok and a beautiful thing because ‘we created you.’ Every stage is different and each conversation is started because of a new encounter of information,” she told the Asian Journal.

While history classes at school cover certain historical moments like slavery, segregation and the civil rights movement, Fontanilla has sought other venues for teaching her son about black history, such as going to museums and watching movies.

“Of course this needs to be appropriate. I remember my son watched ‘Hidden Figures’ with me and it gave him the perspective of how black women were treated in the workplace. What’s important for him to note is how white people mistreated these people based upon the color of their skin and see how life back then included using separate bathrooms and drinking fountains,” she said.

An added layer for black families is “the talk” about what to do and not do when confronted by a police officer.

Taylor said she and her husband spoke to their children when they were preteens about how to manage if they are stopped.

“I don’t remember the exact words, but I do remember that it made me sad and mad enough to secretly excuse myself from the dinner table and cry alone in the bathroom. I never had those talks as a young Filipina girl. I do know what it feels like to be thought of and treated inhumanely,” Taylor said.

For Alvarez-Mitchell, it was brought up following the death of Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old black unarmed teenager who was shot by a neighborhood watch volunteer in Florida in 2012. Martin’s death and the acquittal of his murderer subsequently ignited the Black Lives Matter global movement.

Her children were told to be aware of their surroundings, to not be out and about alone, and to stay calm and not escalate a situation if someone is trying to harm them. When her older kids got their driver’s licenses, the conversations shifted to what to do if they get pulled over, which included tips like keeping hands visible and to not fight back with the cops.

“These were very no-nonsense conversations. We simply had to tell them that this is the reality they have to deal with. I remember that they asked questions about what if the cops did this or that,” Alvarez-Mitchell said. “We had to tell them the truth: that a cop can do whatever to them, they simply must take it. Even if the cop does anything wrong, the only focus is to get away from the cops [and out] of the situation alive.”

Following the more recent deaths of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd, families are balancing the collective emotions in the household as well as how they can stand in solidarity and use their voices.

It’s important that parents create a space for their kids to process the events, especially as graphic images and videos are played out online and on the news — including the videos of Arbery and Floyd which have been widely shared.

As children often receive cues from their parents, Fontanilla made it a point to remain calm when reacting to current events and passing the information to her son in terms he could grasp. It also initiated part of “the talk” between the two of them.

“I had to explain that the events are not just stemming from one incident but rather a culmination of what has been happening for centuries. I had to explain about how we are to treat and respect different cultures and that not all cops are bad. If he hears anything that is hurtful, he needs to remember that those are lies and not the truth. I reminded him that it will hurt and I saw that it made him sad as the tears welled up in his eyes. I started introducing the idea to him that he needs to be aware that as a black person, there are things that he needs to take extra precautions on because of his skin color,” Fontanilla said.

Maria Hendy, a mother in Burbank, California, said that while there were no explicit discussions about racism and discrimination through the years, her 19-year-old daughter Harmony is participating in protests and engages in discussions at home about what she sees in the media.

“Now that she is 19 and these protests are going on, she is listening and she has the understanding of the situation. We will watch the news together and she will listen to what her dad will say. She has several friends that are walking [in] the protests and she will tell us that there are some incidents on the protests that are not being shown on TV,” Hendy told the Asian Journal.

As Taylor’s children are now young adults, they are processing and reacting to the events differently in their own ways, but she and her husband reiterate that they are “strong, smart and resilient.”

“We are having raw conversations about the injustice of being black. One of my kids is angry that her non-black friends and family did not know how much pain black people are in and what has led up to this point. Another one of my kids feels that nothing is going to change and has resigned to life being unfair,” Taylor said. “We are still in the middle of the storm so it is hard to say how we will come out with this. But we are giving our kids the room to express their emotions and individually letting them approach the issue with whatever they feel is best for them.”

While the whirlwind of emotions is valid, Alvarez-Mitchell’s family is trying to be proactive and see a glimmer of hope in the protests and calls for change.

“We have a myriad of emotions from sad to angry to frustrated to helpless at times. But we accept that this is our reality. So now [we] are trying to focus our efforts on how to create change. We are focused on protesting, educating our social circles of the black American reality and changing the narratives we are seeing from certain media outlets. We are also trying to keep some level of hope through it all,” she said.

On social media, many Fil-Ams have expressed the tough discussions they’ve been having with older relatives about anti-blackness, colorism, colonial mentality and internalized racism.

For biracial Fil-Ams, they have shared encountering microaggressions or ignorant remarks from other Filipinos or even extended family members about the color of their skin or their appearance.

“There are ignorant people who do not understand the damaging effects that are said, and that can come from people you would least expect it to come from. In the Filipino culture, one of the saddest things I have experienced is that there is no tact. Statements are said almost with no regard, [like] ‘You’re taba!’ or ‘Sobrang itim mo!’ The part that is sad is that in our culture, we’re taught to respect our elders. So this makes it difficult when we want to defend what is right, but then that can come off disrespectful when you’re trying to make your point and correct what is wrong,” Fontanilla said.

Alvarez-Mitchell emphasized that their children have the right to respond and express how certain comments have made them feel but to be respectful in the delivery. It can also be a teaching moment for both parties.

“Stay patient. Family is important. So try to forgive ignorance and focus on love and respect for your family member. Even when you are pushed by them, stay calm,” she said. “When family gets too much to bear, express your feelings. Be firm about how you see things. Never let a family member’s misguided beliefs go without stating your differing point of view. Your voice matters. But remember that you won’t always change their opinion or vice versa. Just ensure your family does not minimize your opinion or voice.”

Thank you for gathering the thoughts of Fil-Ams moms doing their best to navigate through these times with their interracial families. This is an issue that could no longer be avoided and that our own Filipino culture needed to become aware of. Praying that change, compassion, love, and open-mindedness will arise from all of this.