“I REALLY wasn’t interested in space,” confesses Josephine Santiago-Bond, while reflecting on her engineering education during a recent interview with the Asian Journal.

The Filipina-American engineer never anticipated that her experiences would culminate in a career revolving around missions and exploration in outer space.

It was 15 years ago when Santiago-Bond first landed an internship at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)’s John F. Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Today, she’s the head of the Advanced Engineering Development Branch at the center, a division she helped create that extends engineering support to the agency’s various missions in space, on Earth and other planets.

Budding engineer

Born in the United States to parents pursuing their Ph.D. studies, the family moved back to the Philippines a few months later, where Santiago-Bond would grow up and study until college.

Coming from a family of scientists and doctors, she was naturally curious about the science field as well. One of her earliest memories was testing acids and bases on indicators her mother had brought home.

“I loved the color combinations that I got from playing with that kit, but it created a really vivid memory that I think really influenced me to get into sciences,” she says in a NASA video.

At 12 years old, Santiago-Bond passed the national competitive exam and was accepted as a scholar at Philippine Science High School, a selective public high school that specializes in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education and is considered the top science school in the country and one of the best in the ASEAN region.

When it was time to apply for college, she said she was “undecided” about a major but was attracted to engineering, particularly electronic and communications, after speaking to a former schoolmate who was a freshman studying that discipline at the University of the Philippines (UP).

“I couldn’t tell you what she said but I remember feeling really excited about taking electronic and communications engineering,” Santiago-Bond recalls. She enrolled in the five-year program at UP, where she graduated in 2001 with a Bachelor of Science degree in that engineering specialty.

Other profiles written about the engineer have dwelled on her difficulty in some math courses as an undergraduate, but those shortcomings didn’t detract her from graduating and proving that she was meant to be in this field.

“I take pride in being a product of Philippine education as it speaks to the high quality of education that is available in the Philippines and how graduates can successfully compete internationally,” she says.

Her first engineering job out of college brought her to South Dakota for Daktronics, Inc., which designs sports products like scoreboards. She simultaneously pursued a master’s degree in electrical engineering at South Dakota State University (SDSU).

“To be frank, my motivation was to get a U.S. education because not only was I trying to get a job here in the U.S. but also because I had mediocre grades in undergrad and this was a do-over for me to go to grad school and get better grades,” Santiago-Bond says.

NASA calling

“…I want to contribute in some way to the mission of space exploration,” proclaims Santiago-Bond.

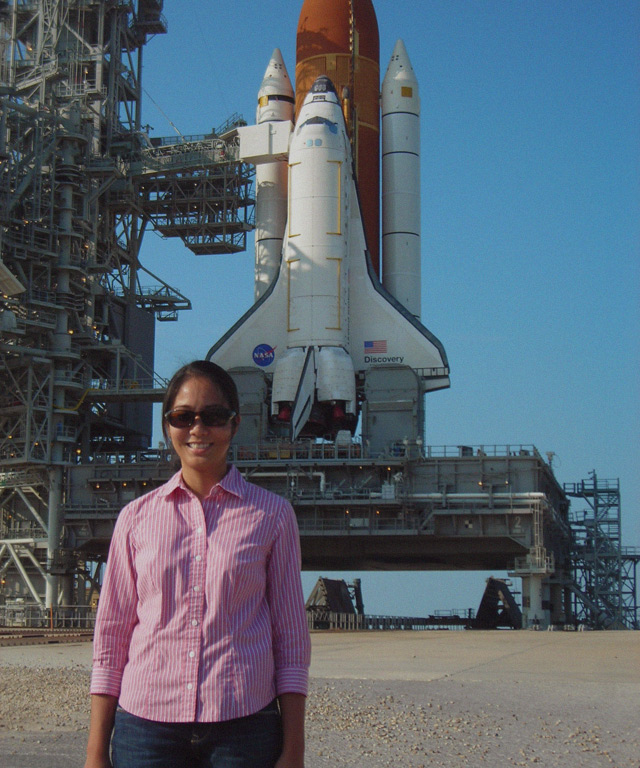

She took on a second job as a research assistant under an advisor who received funding from NASA’s Space Grant Consortium. An opportunity to spend a summer at Kennedy Space Center (KSC), one of NASA’s 10 field centers in the country, presented itself because the university didn’t have a facility for the project she was working on that involved hazardous gases.

“That was the second winter I had spent up there [in South Dakota] and it was pretty frigid so I was excited to spend the summer with him at KSC,” she recalls.

Her period at KSC, coupled with the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003, further piqued her interest in NASA — as did applying her engineering expertise to aerospace research and development.

“I’m kind of embarrassed to say prior to that incident, I didn’t really know about space shuttles and that there was an International Space Station orbiting around us,” Santiago-Bond says. “I felt very sad about the lives that we lost with Columbia and became in part obsessed with the TV coverage of the recovery.”

She adds, “If any good can come out of a disaster like that, I can say that was the point at which I truly started learning and getting interested about NASA and space in general.”

After spending the summer in Florida, she applied and was accepted as a graduate intern at NASA in 2004, where she would go on to spend two semesters.

It soon translated into a full-time, post-grad offer a year later as an electronics engineer in which she had a hand in the design of new technologies and Constellation subsystems, and space shuttle ground system operations.

“I chose to work here and I’ve stayed…I’ve been here about 15 years. The people around me are great…to work with,” Santiago-Bond muses. “I enjoy living on Florida’s coast and really the biggest thing is that I want to contribute in some way to the mission of space exploration.”

Through the years, NASA has offered continuing education and professional development, which she says have helped her become “more self-aware.”

She later transitioned to systems engineering with a graduate certificate program, which the agency subsidized, to hone into more of her identified underlying strengths, such as being able to communicate with a team of people and solving technical problems.

“It’s great to come to work every day because I can be myself and my values align with the organization’s values. They always emphasize safety, integrity, teamwork and excellence and those are things I line up behind,” she says. “It’s very rare to find an organization that carries a mission to drive and advance in science and technology, aeronautics and space exploration with just the very simple desire to enhance knowledge all for the benefit of mankind.”

Another career milestone was being part of the agency’s Systems Engineering Leadership Development Program (SELDP) in 2012, a competitive agency-wide program for high-potential system engineers to have access to courses, workshops, coaching and mentorship.

The program placed her in a year-long assignment at Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, which was a slower-moving and smaller environment compared to KSC.

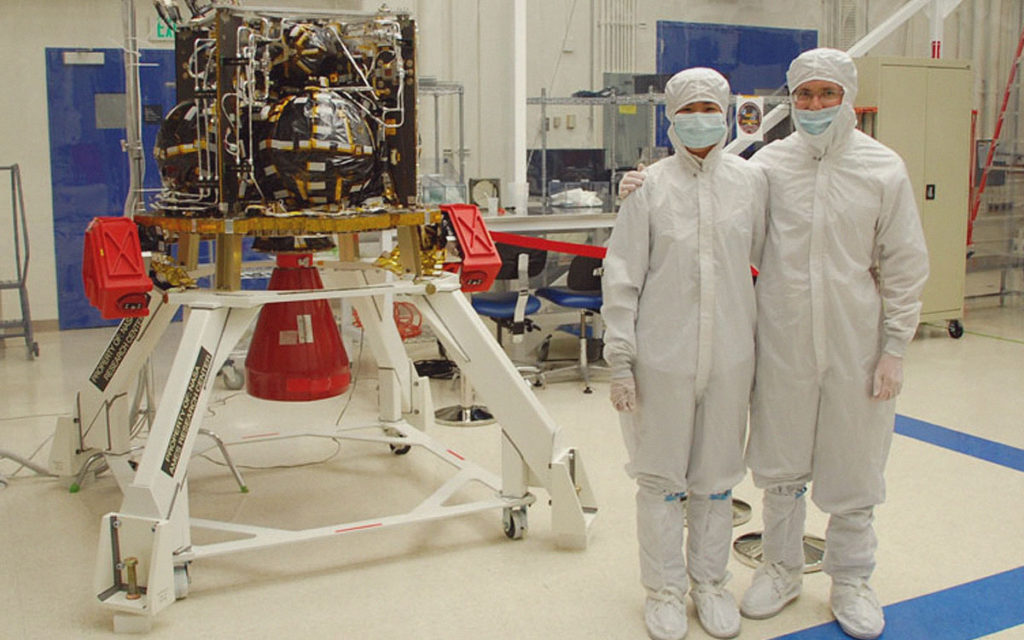

While there, Santiago-Bond was on the mission systems engineering team for the Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE), a spacecraft mission that orbited the moon in 2013 to gather detailed information on the moon’s thin atmosphere and whether dust is lofted in the lunar sky. Her responsibilities included ensuring that the LADEE passed its follow-up review and communicating with other NASA centers involved with the integration.

“I’m proud to have been part of the integration and test of LADEE. It’s a spacecraft that orbited the moon for five months and intentionally crashed on the far side of the moon. The mission actually far exceeded the 100 days that it was meant to,” she reflects. The mission lasted 160 days after it crashed onto the lunar surface in mid-April 2014.

In her nearly two decades at the space agency, she quickly beams a list of several projects she’s worked on: the tail-end of the historic Space Shuttle program, which ended in 2011; and the formulation and launch of the Ares I-X in 2009, a 327-foot tall unmanned rocket that was part of the research on the future of space exploration post-space shuttle.

She also contributed to another lunar exploration mission called Regolith and Environment Science and Oxygen and Lunar Volatiles Extraction (RESOLVE), which had aimed to put a rover on the surface of the moon in 2017 for nine days to map water ice and other compounds.

After the year at Ames, she returned to KSC under the Ground Systems Development and Operations program and went on to be the chief of the newly formed Advanced Engineering Development Branch.

“Out of all of those, my greatest source of pride is in establishing my current branch from scratch,” Santiago-Bond says. “The organizational culture change that goes with establishing a new branch is by far more challenging to me than any of the technical issues that we had to address as a group.”

On a typical day, her day is structured with scheduled meetings and administrative and technical tasks, but she keeps an “open-door policy” for those under her supervision or spends time with them in their workspaces. “I listen to them, problem-solve with them and provide them with constructive suggestions and I ask for feedback. When I’m not with them, I advocate for them with our stakeholders and to our management,” she says.

Her leadership position comes with overseeing 21 engineers and three interns across various engineering disciplines, providing that “support for exploration, research and technology across the agency.”

“I always feel that I am valued, not only for my engineering and leadership skills, but also as an Asian American and as a Filipina-American, who brings a unique set of experiences and ideas to the table every day,” she says. “I’m not the only female Filipina-American, nor am I the first, who is in a leadership position at NASA, which in itself makes me proud.”

She and her team currently have a portfolio of 70 projects that have to do with Earth (“to improve tasks…so they can be more accurate, faster and safer”), Mars, the moon, and space in general.

For the more complex operations in space or another planetary surface, Santiago-Bond facilitates engineering support where she can “find maximum alignment between what the project needs in term of skill and what the strengths of my employees,” she explains, mentioning that she takes their career goals into consideration.

“On rare occasions when I find that there is no good fit with anyone in my branch, then I identify where I can find a better fit and I facilitate the negotiation,” she says. “Out of all the different things I do in my job, the care of my engineers is the most important aspect…I have the responsibility of removing and identifying the obstacles in my engineers’ way so that they can focus on being the high-performing engineers that they are.”

There are a handful of activities Santiago-Bond discloses that her team is brewing, such as sending hardware to low-Earth orbit and a moon exploration mission set for 2020 that could go into testing by later this year.

“You might see our contribution in a satellite servicing mission that’s set to launch in 2020. You’ll see us extend the life span of an existing satellite even though that satellite wasn’t meant to be serviced in orbit. You’ll see some in-situ resource utilization — different projects that allow us to plan long-term human presence on the moon or Mars,” she hints.

Taking the giant leap

Santiago-Bond bears a sense of duty with her identity as a Filipina-American and the perspective she contributes to a large organization like NASA. She previously served as the chair of the center’s Asian Pacific American Connection Employee Resource Group.

“My leadership position also points to how NASA values diversity and practice of inclusion on a daily basis. I always feel that I am valued, not only for my engineering and leadership skills, but also as an Asian American and as a Filipina-American, who brings a unique set of experiences and ideas to the table every day,” she says. “I’m not the only female Filipina-American, nor am I the first, who is in a leadership position at NASA, which in itself makes me proud.”

“I love that NASA’s policies have assisted me in both as an engineering supervisor and as a wife and a mom…” Santiago-Bond reflects. “Looking back, I never thought I would get as far as I have.”

Recent data from 2012 show that one-third of NASA’s employees are women, with 30 percent supervisors and 20 percent engineers, according to the National Women’s History Museum. Five years later, 37 percent of the agency’s new hires were said to be women. The increase comes as some progress when the agency and STEM fields as a whole are traditionally male-dominated.

While the agency, like other STEM-related organizations, pushes to employ more women and individuals from diverse backgrounds, Santiago-Bond says women who are interested in being in the field need to see other women already doing it. “I would advise them to find a mentor, someone who is capable of helping them overcome, either real or perceived obstacles preventing them from entering the STEM field,” she says.

“The biggest obstacle in having more women in STEM is the lack of interest. Being interested requires them to picture themselves in that situation,” she says. “I would say to them, ‘don’t be afraid of being the only woman in the class…or the only woman in the meeting’ if they’re actually practicing a technical profession. A second woman will come along and they would have done her a favor by being the first. Believe that they bring value and just go do it.”

With Women’s History Month this March, it’s fitting to remember the women who became before Santiago-Bond like Kitty O’Brien Joyner, the first woman engineer at NASA; Dorothy Vaughan, the first African American manager at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NASA’s predecessor); Mary Jackson, the agency’s first African American female engineer; Katherine Johnson, a mathematician whose calculations were critical to the success of the first U.S. manned spaceflight; Sally Ride, the first American woman in space; and the late Angelita Castro-Kelly, a Filipina who was the first woman to be NASA’s Mission Operations Manager for the Earth Observing System.

At the end of this month, two women astronauts on the International Space Station, directed by woman flight controller, are expected to mark the first time in history that an all-female crew will do a spacewalk.

“That’s very empowering to work in a workplace that embraces that diversity and inclusion and gives us an opportunity to give back to the nation and the world,” Santiago-Bond says.

As for more career benchmarks to hit? Another goal of hers is to do more community outreach and be a shining example that there’s no straight trajectory for a STEM education — and that there’s redemption after not-so-perfect grades because learning is a life-long journey — as well as proving that having a career in the agency is possible while being a mother.

“It’s me now trying to follow my pursuit of work-life balance. My priorities have shifted over the years. I became a wife 10 years ago and a mother five years ago,” Santiago-Bond says. “I love that NASA’s policies have assisted me in both as an engineering supervisor and as a wife and a mom. I can work anywhere and my time is pretty flexible within the policies and that allows me to continue to give my best to NASA and be there for my family when it matters. Looking back, I never thought I would get as far as I have.”

Dear Christina and Asian Journal,

Thanks for your article on Josephine Santiago-Bond. It is an inspiration to see women and a co UP alum like her. Congratulations for featuring women specifically in STEM. I am particularly interested in contacting Josephine because of my project in Chicago. She will be a great inspiration and will likely inspire a lot of my students. I established an engineering program and is currently funded by the National Science Foundation to increase underrepresented population in engineering especially women. I target students who has difficulty in math, create programs to help them pursue a degree in Engineering. My project is already published in Suntimes magazine but I need real inspirations. Josephine is one one of them. I am really writing thing for two reasons: 1) to congratulate you and second to ask if you can connect me to Josephine so I can invite her as speaker even in Skype.

Thank you.

Doris Espiritu

Director of Engineering Program

[email protected]