“I DON’T feel any more free than I do when I’m on that stage in front of a microphone,” Filipina American rapper and spoken word artist Ruby Ibarra says.

Before she takes the stage, she collects herself and starts organizing lyrics in her head. It’s a meditation of sorts until she’s out in front of the audience, then it’s “autopilot” mode from there.

“The nerves help give me that adrenalin I need to be able to perform. When I lose that sense of nerves, that’s when I feel like I should be wondering, ‘Is the passion still there?’” Ibarra says. “The fact that I get nervous before I get on stage means I do care about what the audience will perceive the show to be and I still very much care about my craft.”

It’s been two years since the release of Ibarra’s first full-length album, “Circa91,” but she wants the community and music industry to know that she’s “out here” and still has a lot to say.

When we have our conversation, Ibarra gushes about her anticipation of attending the Grammy Awards the next night for the first time. “Hopefully we’ll be at the Grammys next year again. I’m just going to speak this into existence that somewhere down the road, we’ll be on that stage,” she proclaims.

“I feel like I’m here at a time when the community has me on their shoulders and I think that completely challenges the notion of crab mentality,” Ibarra muses.

Ibarra, who was born in Tacloban, Philippines, moved to San Lorenzo, California at four years old.

One of the tangible remnants carried over from the homeland was her mother Evelyn’s cassette tape of Filipino rapper Francis Magalona’s (whose stage name was FrancisM) album “Yo!” Ibarra recalls being able to recite the lyrics at an early age because the album was on loop “in the background constantly.”

“It somehow introduced me to music and I ended up falling in love with it. I ended up memorizing the lyrics, being a little kid reciting ‘mga kababayan ko.’ I think at the time, I didn’t really fully fathom the socially conscious themes that were very much integrated in his music,” she narrates.

With threads like colorism — the culture of skin tone discrimination in the Philippines — to unifying Filipinos found in FrancisM’s music, Ibarra would continue those conversations two decades later from the lens of a Filipina American millennial raised in the Bay Area.

As a teenager, Ibarra started writing her own poetry and rhymes, which led to learning music production and eventually performing publicly at colleges and local venues. By 2010, she made her own videos on YouTube and two years later, she released her debut mixtape, “Lost in Translation,” hosted by DJ Kay Slay, which premiered that same night on Shade 45 Satellite Radio in New York City.

Ibarra studied biochemistry and molecular biology at University of California, Davis and is a scientist by day, but turns into this musical force by night and on weekends. She released “Circa91” in October 2017 under independent label Beatrock Music, which has Filipino artists Bambu, Rocky Rivera, Klassy and more in its catalog.

The 18 tracks on the album — some of which are interludes that tie together Ibarra’s experience — were all challenging to write, Ibarra admits.

“Circa91,” which was fittingly titled after the year her family migrated to the United States, was her chance to get raw about the layers of her personal identity and history, which she had kept at a distance before the album. The manner in which she speaks is introspective, yet flows in a way similar to her music wherein she emphasizes certain words and pauses in between statements to let them sink in with the recipient.

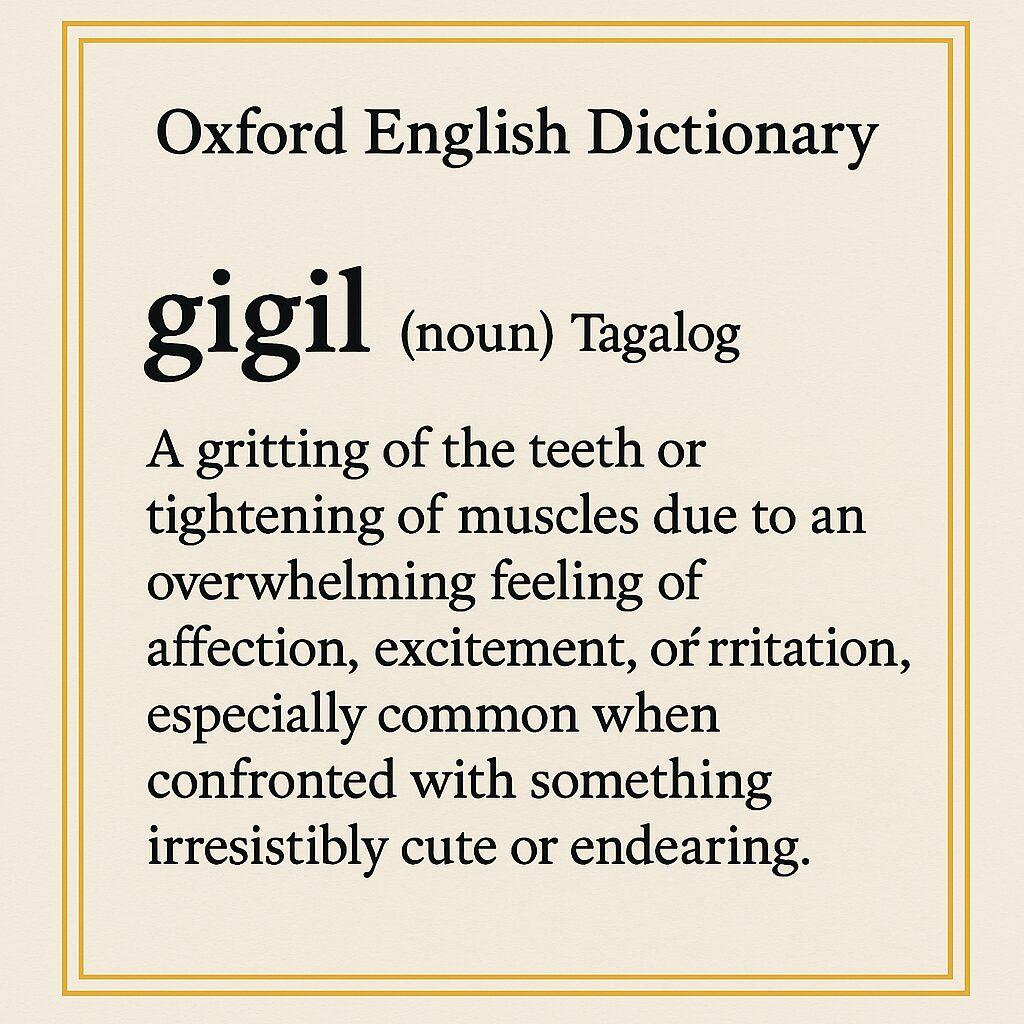

She brings listeners into her world to learn where Ruby Ibarra is coming from and who she is, while infusing English, Tagalog and Waray, the language spoken in the Eastern Visayas. For example, the second verse of Playbill$ is entirely in the latter language, which she has said that in addition to Tagalog, is perfect for hip-hop.

“Prior to the album, my approach as a rapper was trying to prove myself on the mic and show people my lyrical abilities and expand my lyricism, but I wouldn’t really show people who the person was behind the microphone,” she says.

On “Background,” Ibarra narrates the experience of being scolded after playing in the sun and being scrubbed by whitening tools like papaya soap: “They say papaya soap only works when it burns. And It burns deep. So scrub harder / When we played outside on hot days, our mothers would say we smell just like the sun / You don’t wanna be in the sun…they all say / We are taught to fear darkness but ironically find solace in the shade / But this skin, was built to change colors like chameleons.”

“With ’Circa 91’ or the poetry I write, I see how much they are similar to the themes that FrancisM was talking about,” she says. “I think it’s coming full circle.”

In addition to the late Filipino rapper, Ibarra credits listening to Tupac, Wu-Tang Clan, and Lauryn Hill as furthering her interest in hip-hop and music in general. Wu-Tang’s music inspired her to learn more about boom rap and experiment with different lyrical techniques, while “The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill,” was the “soundtrack” of Ibarra’s formative years.

“Being influenced by that and seeing the power of storytelling through the medium of music are what inspired me to try to delve into that and try to make music on my own,” she says.

She adds, “I find it important more than ever to use my platform to share my voice because I can provide that sense of identity for someone else, just like how I felt as a little 5-year-old girl listening to Lauryn Hill. If I could give, even just 1% of that feeling that Lauryn gave me to someone else, then I feel like I’ve accomplished what I’ve wanted to do with my art.”

“…when I think about the identity of what it means to be Filipina, it’s to be completely resilient, strong, and selfless,” Ibarra says.

Mainstream influences aside, Ibarra candidly draws from her lived experiences teetering two cultures, questioning where she fit in, and being raised by a single mother.

“These are people who don’t necessarily have a platform to share their experiences,” she describes. “We never hear about the story of a single parent, Filipina immigrant in the middle of the Bay Area or we don’t hear about the story of a Filipino immigrant who came to the U.S. in his 30s and couldn’t find a job. Why can’t we glorify and amplify those kinds of voices as much as those we hear in the mainstream?”

In “7000 miles,” she recounts about her family’s immigrant experience “7,000 miles away from home with language barriers” and trying to fit into American culture (“Mama said to learn their way, every day I emulate / ’Til identity erased, overcome by inner hate”).

On “Broken Mirrors,” she speaks about growing up without a father and being raised solely by her mother. “Reflections of a 5-year-old lookin’ in the rear view / Wonderin’ why she ain’t got a father like her peers do,” she bares.

“I got to show the vulnerability and show people what I experienced growing up and who I truly was,” Ibarra says. “‘Broken Mirrors’ was one of the most challenging because I really reflected and looked back at my personal life.”

There are moments when she’s not afraid to get political with references of what’s going on back in the Philippines, call out rape culture and toxic masculinity, and unpack colonial mentality. On “Taking Names” (feat. Bambu and Nump Trump), she talks about the Philippines and the Filipino people being colonized by Spain and the United States.

“From Morro Bay to the East Bay, we stay survivin’ where we stay / They keep invading’ where we lay, there’s no debating’ that we pay / That naval base up in Subic Bay / To all the places that they tried to take / From Magellan’s days to Philip’s raid / When the land was raped and they changed the way.”

One of the standout tracks of “Circa91” is “Us,” featuring Rocky Rivera, Klassy and Faith Santilla, which has taken a life of its own and has become an empowering Filipina American anthem. Its music video, which Ibarra directed, features over 100 Pinays, as well as costumes from different regions of the motherland.

“Island woman rise, walang makakatigil / Brown, brown woman, rise / They got nothin’ on us (aye!)” Klassy chants in the hook.

Early on in the writing process, Ibarra knew she wanted to bring on a “multitude of female voices” after noticing that the woman’s perspective is still largely missing, even in immigrant stories. The first verse has the lyrics: “Yo f*ck a story arc if it don’t involve no matriarchs / Our mothers work from the ground up.”

This song was a way to “dismantle the patriarchy and that notion that the Filipina has to always be on the sidelines and be the backbone to the men and always in the background,” Ibarra says. “To have a track like that, where we’re celebrating sisterhood and feminism, we’re showing, not just in rap, but in our community that we’re out here.”

“Women are more important than ever and we’re not one-dimensional characters that the media perceive us to be,” Ibarra says. “There are so many stories and so many different voices and it’s important to amplify these different perspectives because when we say ‘woman,’ it’s not just one story that can encompass the identity of all women.”

Ibarra said that if “Circa91” is any indication, she has a following and people are listening.

“It was because of the reception of the last album and these last shows I’ve been doing that have been affirming to me as an artist where I realize there are people who want to hear the things I talk about and who feel like they’re represented through my music and are seen through the music videos,” she said.

In 2018, a year she says “gave [her] the best memories of life so far,” she collaborated with SZA on MasterCard’s ‘Start Something Priceless’ commercial leading up to the Grammys. The Filipina American rapper was featured on billboards in New York’s Time Square and across from Madison Square Garden for the campaign. It’s an opportunity she “would have never expected to happen in a million years.”

“When we see these big mainstream artists in the spotlight, we believe oftentimes it was an overnight success. That’s really not the case. I can speak for myself that…this is years and years of working on my craft, investing in myself and trying to put myself out there. You have to remember to keep putting in the work and keep practicing and perfecting what you’re doing,” she says. “If you’re authentic in what you do, if you actually speak your truth, then people will take notice of that and people will eventually listen and love what you’re doing.”

Ibarra continues to tour “Circa91” nearly two years later around the United States (some upcoming performances this summer include Levitt Pavilion in Los Angeles and the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, D.C.) and in the Philippines, including Malasimbo Music & Arts Festival this past March in Puerto Galera. Currently, she’s in the process of writing and directing a short film version to accompany the album.

Audiences can expect Ibarra to drop another album this October, just in time for Filipino American History Month.

“I feel like I’m here at a time when the community has me on their shoulders and I think that completely challenges the notion of crab mentality in our community,” she said. “A lot of people are lifting me up and want to see me succeed and I’m very honored and humbled to see that happen. At the end of the day, I want to see us all rise up together.”

She credits seeing Filipinos like Darren Criss sweeping major awards like a Golden Globe, R&B artist H.E.R. winning Grammys, and Bruno Mars selling out arenas around the world as a “pivotal moment for Filipino Americans in the entertainment industry.”

“The fact that we’re seeing these representations of people who look like us, we’re seeing a shift in Hollywood as well. This is the perfect window and opportunity for artists like myself to just jump in and do our thing and support each other more than ever,” she says, putting out a call to support other Filipino American art and stories to “build each other up and increase visibility for us.”

From the lolas (grandmothers) who spend their retired time raising the kids to the titas (aunts) who share the role of motherhood to the nanays (moms) who do everything they can to keep the family afloat, Ibarra hopes to honor them with her music.

“After having met so many Filipinas this past year who are all inspiring, incredible and powerful, coupled with my experiences with my own mother, when I think about the identity of what it means to be Filipina, it’s to be completely resilient, strong, and selfless,” Ibarra says.

“Women are more important than ever and we’re not one-dimensional characters that the media perceive us to be. There are so many stories and so many different voices and it’s important to amplify these different perspectives because when we say ‘woman,’ it’s not just one story that can encompass the identity of all women.”