For a lot of people, the moment that shifted the current incarnation of the fight against police brutality was when people across the world en masse gathered in the name of George Floyd.

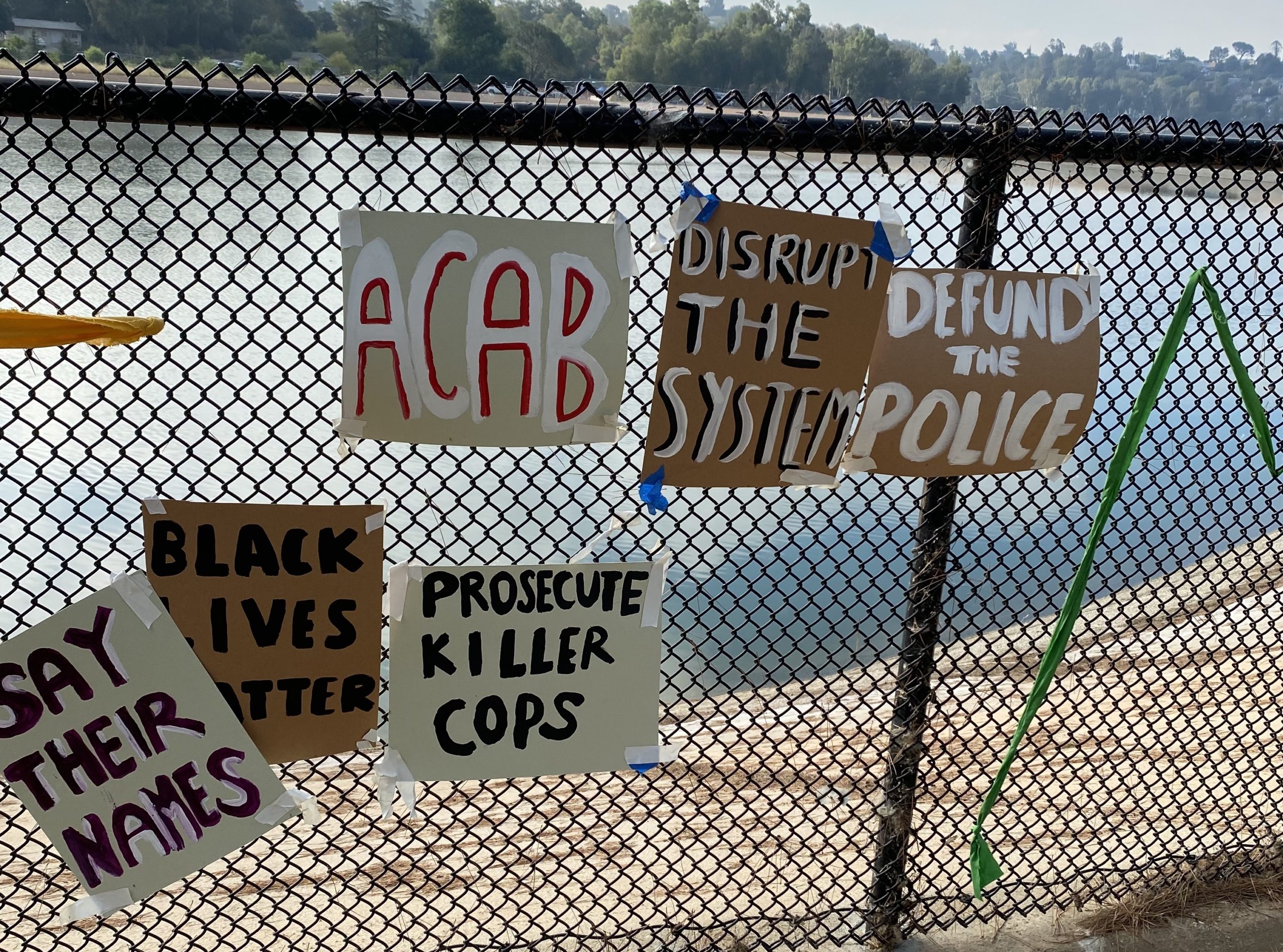

Since the massive Black Lives Matter protest in Los Angeles on Saturday, June 6, the movement’s momentum has only increased, calling for a long-overdue reexamination into policing practices and the deeply-rooted anti-blackness that informs them.

The killing of George Floyd was the last straw in a country that, since the 2012 killing of unarmed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, has undergone a social justice transformation that has defined and emboldened a generation that has finally had enough.

But if Martin’s killing and the ensuing formation of Black Lives Matter as a campaign catalyzed a cultural transformation into a “woke” era, the killing of Floyd has triggered an all-encompassing metamorphosis that is forging recalibrations of standards and practices of law enforcement as well as other industries such as retail, entertainment, health care and more.

What separates this current uprising with past efforts to eradicate police brutality is the emergence of concrete, legislative solutions to the issues that protesters have been calling for, even before the killing of George Floyd.

Twenty-seven-year-old EMT Breonna Taylor was gunned down in her own home on March 13 by police who had a no-knock warrant on the home. On Wednesday, June 10, the Louisville City Council unanimously voted in favor of a ban on no-knock search warrants called Breonna’s Law, which also requires all officers serving warrants to wear body cameras that remain turned on at least five minutes before and after a warrant is served. (As of press time, the officers who killed Taylor have not been arrested.)

In Seattle, peaceful protesters have taken over the boarded-up Seattle Police Department and cornered up several city blocks to establish the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ), a “protest haven” (with no cops in sight) for speakers, artists, musicians to use their talents in the service of fighting police brutality.

In Los Angeles, amid calls to defund the police department and fire LAPD Chief Michel Moore, the city has committed to diverting money from the police department, investigating “officer misconduct” at recent protests and investing more funding toward community programs to uplift “communities of color.”

These significant benchmarks are proving that this pivotal moment in protest is the most comprehensive civil rights campaign of the 21st century, and non-black communities are realizing there’s more to solidarity than just reposting a black square or retweeting a Martin Luther King, Jr. quote on Facebook and calling it a day.

The highly-publicized protests present a moral exercise in attention and endurance, and in an age when trending topics change at the blink of an eye, maintaining a higher degree of fortitude that could lead to greater changes in the name of fairness and equality for the black community.

In addition to participating in rallies and protests, activists and community leaders have been urging people to get involved in other ways, too. Donating to organizations that are dedicated to fighting against police brutality, abuse of power and unjust practices that disproportionately put Black individuals at a disadvantage are among the base-level ways that people can contribute.

“I recently had told someone that it doesn’t have to be all or nothing,” Jollene Levid, a Filipina American Los Angeles-based organizer, told the Asian Journal in a Zoom call.

“Every mass movement in our history that has changed the way a state or government or a country has been run, including the Philippines and the toppling of Marcos. People have found a way to contribute in ways that go beyond what you see as a normal protestor on the streets,” Levid shared.

Right now, the interest in combating police brutality and abuse of power is still hot. But like every major social, political and cultural issue of the Trumpian era when headlines and breaking news change at the speed of light, interest can wane just as quickly as it waxes.

The impact of meaningful refusal

In the acclaimed 2019 book “How To Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy,” Oakland-based artist and Stanford professor Jenny Odell discusses the various ways that attention can be reworked in ways that can best serve a myriad of contemporary conundrums on personal and allied levels, not least of which includes protests and social justice movements.

One of the tenets Odell (who happens to be Filipina American) discusses in her bestseller involves the art of refusal. In the context of social reform, the art of refusal encapsulates rejecting an oppressive, inhumane status quo with the goal to enact just policies and practices.

Providing examples of successful strikes and protests like the longshoremen’s strike in the 1930s and the organized sit-in demonstrations of young black college students in the 1960s, Odell stresses the importance of disciplined stamina and durable thresholds of our attention plays into the art of protest.

The author writes that to undergo a successful demonstration, individuals must begin with fine-tuning their attention which “undergirds every other kind of meaningful refusal: it allows us to reach [transcendentalist Henry David] Thoreau’s higher perspective and forms the basis of disciplined collective attention that we see in successful strikes and boycotts whose laser-like focus withstood all attempts to disassemble them.”

By achieving clarity and effective organizing, protests — and any collective form of refusal — can withstand, even in an age when virtue signaling and optical allyship (the mere appearance of solidarity without any action to show for it) often cloud the movement itself.

The reason that the longshoremen and farmworkers of the 1930s were able to make significant moves was their endurance and denial to budge when their demands weren’t squarely met.

However, nowadays much of our lives and our attention are relegated to timelines, feeds and endless walls of media and, in turn, our collective span of attention has significantly narrowed. Mental stamina, i.e. the ability to devote enough time and interest in any given singular issue, is more difficult than ever.

Like procedural television, the plot of each week’s struggle could change in the blink of an eye; this week the topic of the country is centered around police brutality but next week it could be about something completely different.

Filipinos who are hesitant to see the efficacy in protest should look at the history of revolution in the Philippines, Levid added.

She alluded to the smaller peaceful protests in 1972 that were a direct response to then-Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos’ declaration of martial law, smaller protests and calls for prayer that didn’t tangibly shift the Marcos’ violent regime.

It took intentional and careful maneuvering and utilization of entire communities to establish the People Power Revolution which, in 1986, provided a robust campaign of civil resistance against the violence and corruption caused by the Marcos regime. For the movement to have been successful, it required strength, stamina and a deep understanding of refusal to endure to finally force Marcos to depart.

“Think about how history will reflect the folks that are in the streets now, and think of the People Power movement in the Philippines who were called out by Marcos as agitators and anti-patriotic rebels. But we look at them now as heroes,” Levid said.

In addition to directly donating to organizations, participating in protests and being more conscious voters, perhaps the most crucial first step for the Filipino American community lies in the long-overdue in-community conversations about anti-blackness: where it comes from, identifying it, and coming up with solutions to reverse it.

That starts at the base level, such as with the people at the fore of our lives, Levid said.

“I do think that [fighting] anti-blackness in the Filipino community takes a conversation first, starting with the people in your life that you have to call out, like that racist uncle that everyone has,” Levid shared. “And then do it in a way so that the goal is changing the way they think, which is a lot harder than giving them the middle finger and walking away. It’s much harder because you’re basically organizing your own family, but it’s so important for our community.”

In regards to Filipino solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, there is a propensity to shift focus and lean into distractions and drifting from the core of the movement because of the notion that the push to defund the LAPD bears no relation to the community itself, which Levid and other activists argue, is not the case.

“I would encourage Filipinos to think about the world that they want,” Levid recommended, noting the universality of protests in regards to how a government that places more capital value on police over public education, health care and immigrant rights. “After this uprising, a lot of people see protest and revolution as destruction when it actually offers us this opportunity to be architects of a new world.”

Reimagining law enforcement in ‘a new world’

All things considered, the current wave of Black Lives Matter demonstrations sweeping the nation seems closer to threatening the current incarnation of policing, and that is primarily due to the robust focus placed on the central purpose of holding accountable officers who commit extrajudicial killings and defunding the police.

The latter has taken a significant hold in the last two weeks of protest. In Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti this week announced the city would slash the LAPD’s budget and divert $250 million to youth jobs, health initiatives and “peace centers” for those who’ve been victims of discrimination. ($150 million of that $250 million comes from the LAPD budget.)

Garcetti’s move proves the efficacy of the unrest; in April, Garcetti had signed off on a 7% spending increase for the LAPD that included raises and bonuses for certain officers.

But a large part of the call to defund the LAPD includes slashing the LAPD’s cut of the city’s General Fund.

The General Fund, which is a separate funding reserve that diverts certain amounts of taxpayer money to different government agencies, currently allocates 54% toward the LAPD, more than half of the entire budget.

Among the issues that people can get involved with include the push for the People’s Budget, which not only diminishes the LAPD’s allocation of the city’s general fund, but also would place more funds and resources in other areas of city life like reducing LA’s ongoing housing problem, creating more community youth programs, bolstering public education, small business recovery programs and free healthcare for residents.

“I would ask people, before they make any judgment calls, to think about what our community needs because the possibilities are endless,” Levid said.

LAPD Police Chief Michel Moore said in January that violent crime in the city has decreased, saying then that “it’s one of the safest times in Los Angeles,” according to an LAist story.

And since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, crime has dropped 23% across the city. As the People’s Budget states, instead of allocating more taxpayer funds into officer overtime pay and “aggressive, arrest-driven policing initiatives,” Levid said, suggesting that Filipino Angelenos think about their ideas of a government that puts more investment in the community.

“California has the fifth-largest economy in the world and is the richest state, so why do we have to struggle to pay our bills, house the highest population of homelessness in the country and give our kids a proper education?” Levid shared. “I would ask people to think about that first. That’s a crucial conversation that I think we should all have within our families and communities because everyone will have a role, whether that’s moving their unions, churches and other groups to support the People’s Budget.”

Back to education

But as with every major cultural reckoning, this moment starts with information. Concepts like police abolition, the lionization of law enforcement in the U.S. and institutional racism and anti-blackness have been heavily researched by writers and academics

According to Levid, reading at the rate of a book a week is a regular organizer practice that is crucial to expanding one’s world view and can serve as an important first step for those who want to get involved and learn more about issues like antiblackness and the history of institutional racism in America.

Specifically, black writers can serve as a jumping off point, Levid shared.

Among the authors — who have authored both fiction and nonfiction books — that Levid recommends for everyone, especially Filipinos, include Octavia Butler (“Kindred,” “Parable of the Sower”), Angela Davis (“Women, Race and Class,” “Are Prisons Obsolete?”), Alice Walker (“Hard Times Require Furious Dancing,” James Baldwin (“If Beale Street Could Talk”), bell hooks (“All About Love”) and Toni Morrison (“The Bluest Eye,” “Beloved”).

Contemporary selections that may offer perspectives that are especially applicable to the current movement include “Stamped from the Beginning” by Ibram X. Kendi, “White Fragility” by Robin DiAngelo, “The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander, “Between the World and Me” by Ta-Nahesi Coates, “Just Mercy” by Bryan Stevenson, and “So You Want to Talk About Race” by Ijeoma Oluo.

Mimi Ladell, a Filipina American teacher and librarian based in Bayonne, New Jersey, mirrored Levid’s sentiments on the importance of reading in the effort to stand in solidarity.

“Education, education, education,” Ladell shared in an interview with the Asian Journal. “It’s the root of all successful movements and the best way to start if you want to get involved. It takes longer than and requires more mental investment, but it’s worth it. Nobody can take your knowledge away.”

In the digital world, there is an infinite reservoir of content that purports to be informational but lacks credibility. Facebook is the capital of this digital world, but as numerous investigations have proven, rife are fake news and misleading information on the platform with little to no regulation of facts.

“It sounds like bias because I’m a librarian,” Ladell said with a laugh. “But it’s true that the more you read, and the more variety you have in what you read opens up your world and helps you come up with your own, all-inclusive perspectives, especially [in regards to] issues like race and the culture surrounding policing.”

If libraries aren’t an option because of the safer-at-home mandates that may still be in place, Ladell recommends buying books from national black-owned bookstores like Mahogany Books, Burgundy Books, and The Little Boho Bookshop.

Some Southern California-based bookstores that also have online stores include Eso Won Books, Reparations Club and Malik Books in Los Angeles; Shades of Afrika in Long Beach.

“I’d really encourage people to research alternatives to some popular marketplaces that offer swift and free delivery and opt to purchase books from independent, black-owned stores,” Ladell shared. “Because I think people need to be cognizant of the ways that corporations like Amazon contribute to anti-blackness through crooked labor practices that really put workers of color at a disadvantage.”

For those who don’t want to opt for reading, Ladell also recommends the following documentaries that inform the Black American experience through the lens of racism: the phenomenal documentary 13th directed by Ava Duverney which explores the history of anti-Black racism in the U.S. (available on Netflix); Raoul Peck’s “I Am Not Your Negro,” which envisions an unfinished James Baldwin book; LA 92, which looks back on the Rodney King trial ensuing riots; and “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till,” a reexamination of Emmett Till, the black teenager who was murdered in 1950s Mississippi.

“And this goes beyond just sharpening your individual knowledge. It also helps us become more prepared to educate others within our community. Because that’s kind of what I think the Filipino community ought to concentrate on now: educating our own community,” Ladell said.