IN February 2020, Los Angeles-based social worker Maxie Villavicencio Pulliam took a trip to the Philippines to help with relief operations following the Taal Volcano eruption.

While in Taal, Batangas, where her mother’s side of the family hails from, Villavicencio Pulliam noticed a main road and a monument dedicated to her great-great-grandmother: Gliceria Marella de Villavicencio, an unsung heroine regarded as the “godmother of the Philippine revolutionary forces.”

That moniker was bestowed upon her by General Emilio Aguinaldo on the same day that the Philippine Republic was proclaimed on June 12, 1898.

Growing up, Villavicencio Pulliam never fully grasped why the family’s ancestral home was opened as a museum for the public to visit.

She later uncovered her great-great-grandmother’s storied past and revolutionary ties. Casa Villavicencio was once the secret meeting spot of Filipino revolutionary leaders, such as Andres Bonifacio, General Miguel Malvar and General Eleuterio Marasigan.

“If I don’t know this as her descendant, how much more painful is it to be part of the Taal community and see this name all over the place, but you don’t actually know what she did or who she was?” Villavicencio Pulliam told the Asian Journal.

For the next year, partly due to more free time on her hands during the pandemic, Villavicencio Pulliam set out to write a book about her great-great-grandmother who financially supported the Filipinos’ fight for freedom from colonial rule.

Because two books on her ancestor were out of print, she used translated letters, interviews from extended family members, and online articles to start drafting a story, and attempted to pitch it to literary agents in the U.S. and two publishing houses in the Philippines.

After experiencing rounds of rejection and writer’s block, Villavicencio Pulliam shelved the project. But it wasn’t until last September when she came across an illustrator’s Instagram page that shared the stories of Filipina figures — and one of the portraits happened to be of Gliceria.

The result is “Fierce Filipina,” an illustrated biography independently published ahead of International Women’s Day 2021 that not only captures Gliceria’s life but also depicts a timeless tale of a heroine’s pursuit for equality and social justice. Accompanying the words by Villavicencio Pulliam are vibrant and bold scenes by Manila-based illustrator Jill Arteche.

“My job was getting all the bits and pieces and making it into a book that would make sense for readers,” Villavicencio Pulliam said. “The reason why I decided for it to be an illustrated biography was to make it more exciting, especially for kids, though it’s a pretty high-level book. But anyone can enjoy it, even if they don’t have children or families of their own yet.”

Unapologetically fierce

Gliceria Marella de Villavicencio, known as Aling Eriang, was born on May 13, 1852 to a wealthy family in Taal. Despite her privilege, the book recounts her being friends with house staff and treating them as equals.

At the age of 12, Gliceria enrolled at Santa Catalina College in Intramuros, where she learned the plight of the Filipino people under Spanish colonial rule and began to “think of ways to create change.” However, she received news of her eldest sister’s death and was called back to Taal to manage her family’s estate.

She went on to marry Eulalio Villavicencio, who also came from an affluent background. Together, they lent money to support the revolutionary efforts and offered their home — which Eulalio had given to Gliceria as a wedding gift — as a secret meeting place for leaders.

Gliceria is said to have lent Jose Rizal P18,000 to publish his novels and La Solidaridad, a newspaper that promoted the Propaganda Movement.

“I think the biggest running theme that I don’t overtly say in the book is that no one questioned her authority. She did not let her being a woman stop her from being as active as she could have been in the revolution,” Villavicencio Pulliam said.

In exchange for her generosity, Filipino painter and political activist Juan Luna painted portraits of the Villavicencio couple, a tidbit that didn’t make it into the book. A copy of one of Gliceria’s portraits continues to hang in the ancestral home today, and Villavicencio Pulliam is photographed next to it in the author’s note of the book.

Based on the letters, Villavicencio Pulliam recognized Gliceria’s commanding presence and how she did not apologize for staking a claim in the movement.

“It’s not with any hint of arrogance. She approaches everything as a partner and she’s an equal to the other revolutionary leaders. She comes in and doesn’t say, ‘Please let me know if you need help.’ She comes in and says, ‘I will help.’ It seems to be really effective because people also respect her, listen to her, and go to her for guidance,” the author said.

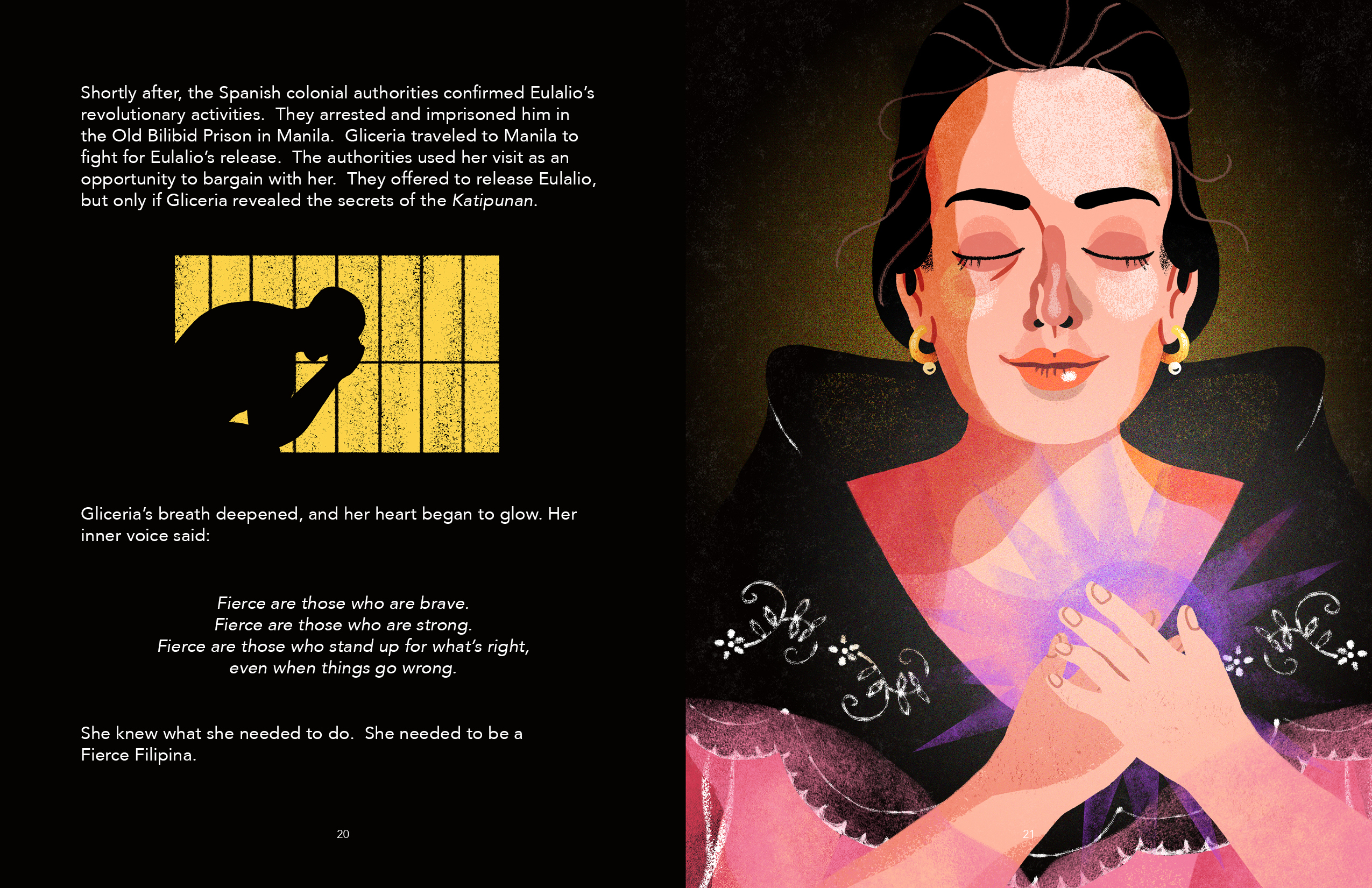

Eulalio was imprisoned in Old Bilibid Prison in Manila by Spanish colonial authorities for his role in the revolution, but Gliceria refused to reveal secrets in exchange for his release. Her husband was eventually set free a year after, but he died three months later due to his injuries.

She did not let her husband’s death be in vain and notably donated her family’s merchant ship, the SS Bulusan, to carry food, clothing and weapons for Filipino soldiers.

Throughout “Fierce Filipina,” Gliceria is presented with challenges in her pursuit of freedom and defending the country. With artistic license, Villavicencio Pulliam embodies her great-great-grandmother’s inner strength and captures it in a mantra.

“Her inner voice said:

Fierce are those who are brave.

Fierce are those who are strong.

Fierce are those who stand up for what’s right,

even when things go wrong.

She knew what she needed to do. She needed to be a Fierce Filipina.”

“That was something I came up with based on some real-life experiences I’ve had as an observer of oppression and injustice. It’s an inner prompting that I feel as a human being but also as her descendant, thinking about what would happen in my body when I know I need to take action regardless of what could be negative consequences afterward,” Villavicencio Pulliam said.

Channeling her great-great-grandmother’s unwavering spirit, Villavicencio Pulliam is living her legacy through her career as a social worker. She has also been vocal about the ongoing anti-Asian hate and hopes this story can be a lesson in boldly calling for systemic change.

“I am trying to live Gliceria’s legacy through this book by teaching people that we have to follow our hearts and if there’s a cause you’re passionate about and want to be a part of, go for it. If you already feel in your body that something’s not right, how do we approach it in a safe, but effective manner?” she said.

“Fierce Filipina” is available for purchase in North America through Amazon, and is set to be printed and sold in the Philippines in the coming months.

“This story is super relevant in any way that readers can take from it. But let’s not stop at Gliceria’s story with Fierce Filipina. Let’s see what else we can explore and find out there that we could use to amplify us as Filipinos and Filipinas in America,” Villavicencio Pulliam said.