ERIN Entrada Kelly is a product of 1980s pop culture, from having names for each Cabbage Patch doll to collecting sticker books to rewatching “E.T.” countless times.

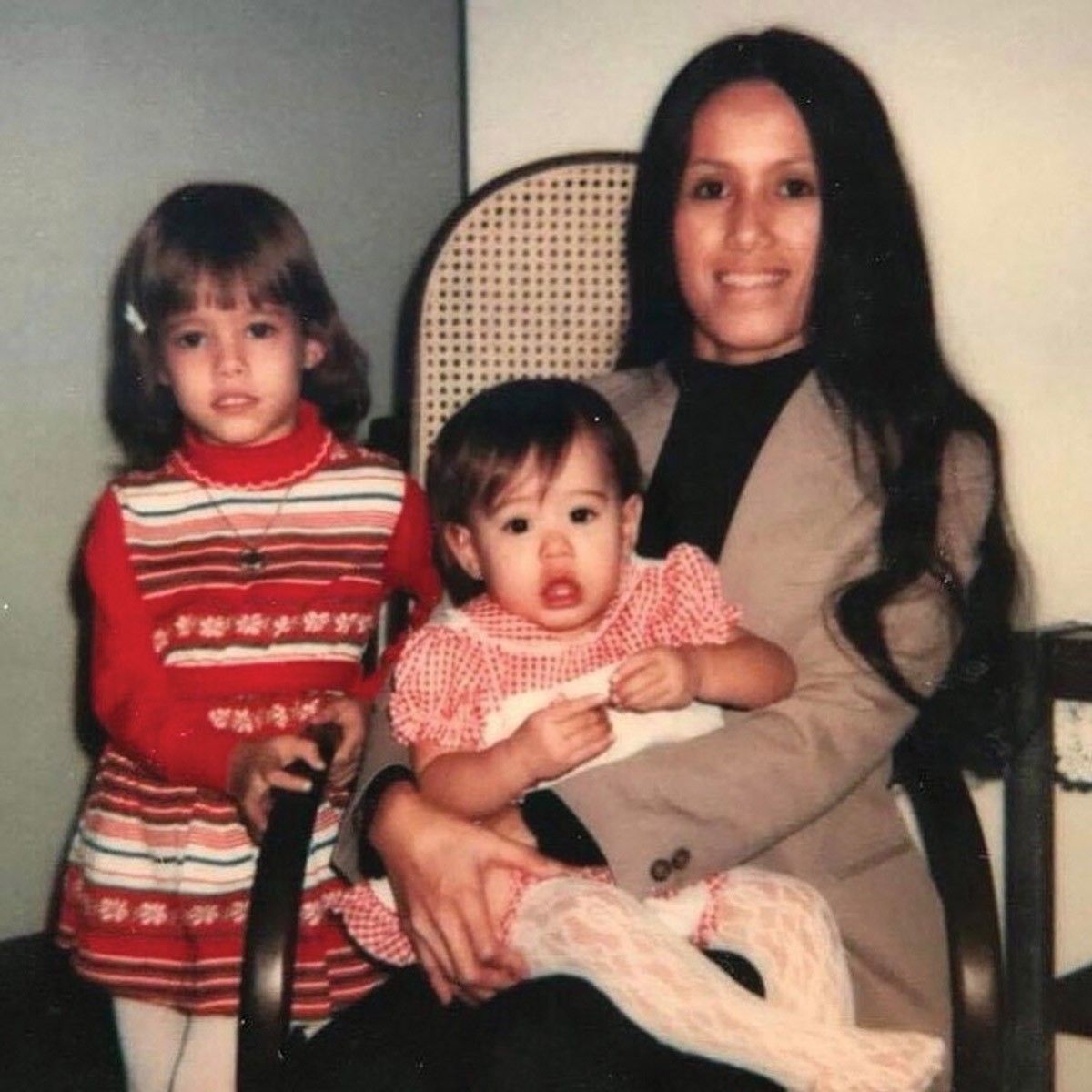

But what the author — who was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana to a Filipina mother and a white father — remembers the most from her elementary school days was when the space shuttle Challenger launched on January 28, 1986 and subsequently exploded, killing all seven astronauts on board.

Decades later, Kelly revisited news about the incident and delved deeper into the stories of the astronauts. With that research, coupled with how the incident has been almost forgotten by subsequent generations of young students, she knew this historical moment would be the backdrop of her sixth middle-grade novel, “We Dream of Space.”

Released on May 5, “We Dream of Space” brings readers into the lives of the Nelson-Thomas siblings, 12-year-old twins Bird and Fitch and their older brother Cash, and the weeks leading up to the Challenger launch.

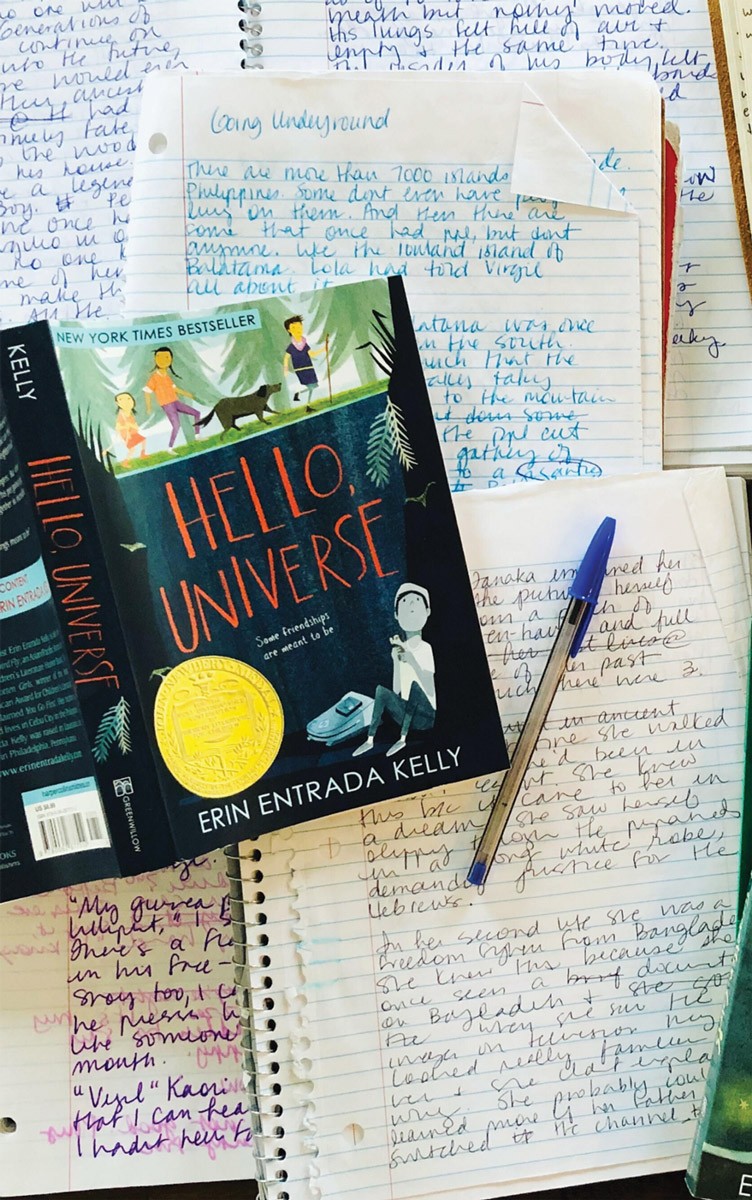

Along the way, we read about Bird’s dreams of being NASA’s first female shuttle commander and the dynamics of this middle-class family in Delaware. We also get introduced to their science teacher Ms. Salonga and see the recurring themes, such as loneliness, found in Kelly’s work, namely “Hello Universe” (2017), for which she received the 2018 Newbery Medal, the most prestigious award in children’s literature.

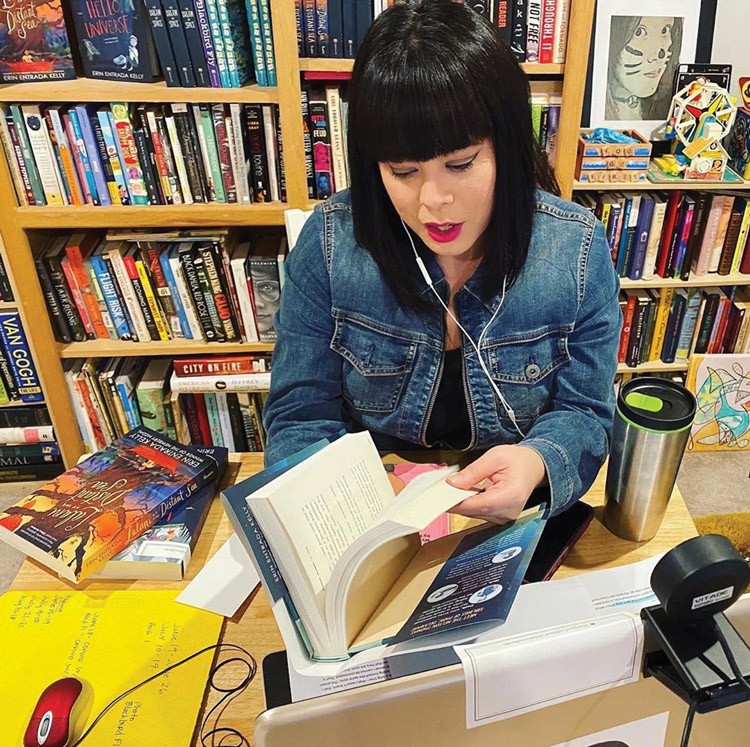

Kelly, a former journalist who is now a full-time author based in Delaware, spoke to the Asian Journal about how her upbringing as a Filipina American has shaped her writing, the development of her latest release, and what’s next for her award-winning novel.

Asian Journal (AJ): You’ve written and released six novels in the past five years. How do you begin developing a story?

Erin Entrada Kelly (EEK): The story kind of grows and blossoms. For several months, I’ll spend time just thinking about the characters and the story. Once I feel like I have it kind of fleshed out in my head, then I’ll get a notebook and start writing things down longhand. I’ll just write down the characters’ names and the seeds of the idea that I have and let it go from there.

AJ: Once you’ve filled the notebooks, do you have sticky notes or other tools to help map and organize the story?

EEK: I’m a very linear writer so I write in order by chapter. Usually I’ll do a chapter outline, but it changes so I’ll cross things out and add things. This is the only mapping I really do. I write several chapters in the notebook and then I’ll type it out. Then I print the whole thing out and go by hand and that’s when I use a lot of sticky notes for revisions I need to make.

AJ: It’s interesting to ask that question to writers and authors because everyone handles it differently. You seem so organized.

EEK: I am completely disorganized and a mess in every other aspect. I never know where anything is and I lose things. But when it comes to writing, I am pretty organized.

AJ: Going back to your first novel “Blackbird Fly,” what was the process of pitching that to a publisher and finding an editor?

EEK: After I published a series of short stories and decided to focus on middle grade and wrote my first middle-grade novel, I had a pretty conventional journey. I queried agents and found my first agent — she’s no longer my agent — and she brought it to editors. It probably took almost a year or two for an editor because I had to do more revisions and such. Then about after a year, I got the offer from HarperCollins, who I’ve been with ever since.

AJ: It’s been two years since “Hello Universe” received the Newbery Medal. How has this award helped your work and how has it been to be among this roster of authors we grew up reading and learning in school?

EEK: It’s surreal every single day. Even two years later, it’s very, very strange, but in a great way, of course. It’s very surreal because you never think that’s going to ever happen. I think the greatest benefit has been a larger platform. The book has been translated into many different languages, which is cool. But honestly the greatest benefit has been the wider readership — and I don’t mean that from a business royalties standpoint — and being able to connect with even more readers, librarians and teachers. I was working full-time when “Hello Universe” first came out and not long after it won, I was able to leave my job. Now I write full-time and do some teaching.

AJ: Also to mention what the book has done for Filipino American representation in literature. You have a Fil-Am central character, Virgil. The book illustrations were done by a Filipina artist [Isabel Roxas].

EEK: Definitely, thank you, yes. That was absolutely a benefit because when I was growing up, I didn’t really have access to any books that had Filipino characters, and even Asian characters or minority cultures of any kind were not really depicted. Next year, actually, I’m working on a chapter book series now that will have a mestiza — half Filipina, half white girl — as the main character so I’m really excited about that too. I’m doing the illustrations as well.

AJ: “Hello Universe” has also been picked up by Netflix to develop it into a movie with Fil-Am screenwriter Michael [Golamco]. Did you ever imagine any of your work would be translated to the big screen?

EEK: No, never! Again, it’s been really surreal. I think right now, they’re still in the script development stage so the production hasn’t gotten started yet. But when that all starts up, I’m really looking forward to it. One of the things they asked me at the beginning was, “What is most important to you about this story?” I said, “The representation!”

Virgil’s Filipino American and then Ori is Japanese American. I didn’t want any of that to change. I didn’t anticipate that they were going to but I wanted to make sure it was important that the representation stayed the same. For Virgil, it’s a very important part of the whole narrative because he has his lola and Filipino folk tales woven in there. They said that was one of the things they loved about the book and it wasn’t even in their mind to cast it any differently.

AJ: How involved are you going to be during the production?

EEK: I will probably not be very involved. I know different writers are involved in different ways but I prefer to not be that involved only because I don’t know anything about making movies and I trust them. I trust Michael [Golamco] — he’s great and very talented. He gets it. I trust that they’re going to do well by the material so I don’t necessarily need to be involved. As long as I know what’s going on and when things are happening, that’s all I really need to know.

AJ: Are there any screen adaptations you’ve particularly loved that did justice to the stories?

EEK: I have to say I did enjoy “To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before.” I’m not huge on book to movie adaptations because I always, of course, prefer the book. But that’s the first recent one that comes to mind.

AJ: Shifting to your latest novel, “We Dream of Space.” It takes place in Delaware, where you currently live, and goes back to the 80s when you were growing up. What led to the development of this story and creating this family?

EEK: The Challenger disaster, I think for a lot of people of my generation and my age group, was one of the biggest events of adolescence. It really stayed with me as it did with other people as well so I knew I wanted to write about it at some point. Also, partly because I feel like it’s been forgotten in a general sense. For example, when I go to schools, I ask students if they’ve heard of the Challenger disaster and almost none of them have. It was a huge news event that has kind of been lost. I knew I wanted to revisit it and have a book set in the 80s because I was a child of that era.

AJ: The central characters are the three Nelson-Thomas children. Though they’re not of Filipino descent, our community can likely relate as they’re from a big family too and we see similar dynamics play out among the siblings and even in their relationships with their parents. For example, we read about the only daughter Bird receiving passive-aggressive comments from her mother about her appearance and role as a girl. How did this family come about?

EEK: The idea started with Bird and I thought it would be interesting to have siblings who are all in the same grade. When I was thinking about Bird and her story and I thought, “Okay, she has these siblings.” Then I thought, “Well, how are they all going to be in the same grade?” So then she became a twin to Fitch and has an older brother, Cash. It’s really underrepresented in literature to see children that fail grades so I thought it was important to have Cash in there.

I’m really glad you mentioned that with Bird because you never quite know what’s getting across or if your intentions are coming through. But my intention with Bird is that she’s the glue of the whole story. Number one, she feels responsible for whatever reason for the tenor of the house so she tries to interject when she can and to manage the mood of the home, which is an unfair and large responsibility for a 12-year-old girl.

She also gets conflicting information from her mother because her mother tells her that looks aren’t important but she also harps on her about gaining weight and not eating that kind of cereal. The three siblings together get conflicting information as well because their parents correct them and tell them to be kind but they’re not kind to each other as they argue all the time and use certain language. That was something I wanted to explore too because adults are very often critical and they operate under this view of “do as I say, not as I do.” It’s a very dangerous way to bring up young people because they can see those contradictions. Bird, Fitch and Cash are getting different information but they’re also not getting the emotional support that each of them needs.

AJ: Through this book, what did you learn about yourself as a writer and what aspects of your childhood and upbringing did you revisit and tap into?

EEK: Of course, on the fun side, I got to explore things like the arcade, a phonebook and cassette tapes — all these things I have nostalgia for. One of the things all my books have in common is that they explore loneliness on some level. In this book, I thought it would be interesting to explore that there are these three siblings and there’s five of them in this fairly modest home. Even though they’re surrounded by family, they’re still very lonely. This concept of loneliness, being within and not without, is something that I wanted to explore because I often felt like that when I was young.

Also this feeling of family floating in its own orbits was something important to me. When I was growing up in south Louisiana, my father was white and his family all lived in the Midwest. My mom’s entire family was in the Philippines so I had so many relatives that I didn’t know or would never meet. They’re all far away so it was a strange, insular experience when you’re connected to your family, but not really connected to them.

AJ: Since you mentioned your two family backgrounds, how did your mom end up in Louisiana?

EEK: They met in the Philippines because my dad was stationed there. He ultimately had a job transfer. He’s originally from Kansas so she moved there from the Philippines in the middle of a blizzard and obviously she had never been around snow before. Then he got transferred to Louisiana.

AJ: And how did you find your way to Delaware?

EEK: I moved to Pennsylvania like eight years and my partner now is in Delaware so we bought a house here together.

AJ: Since the book takes place there, what do you want people to take away from the small state?

EEK: What’s fun about living in Delaware is that when I travel and people ask where I live, I tell them Delaware and they always look at me as if I said I lived on Mars. But the point I wanted to explore as well is that there’s a line where Bird’s brother tells her, “You’re just a girl from Delaware.” Delaware is this underdog state that people seem to forget about. I wanted to show that it doesn’t necessarily matter where you’re from and you don’t have to be from some big exciting place to do amazing, incredible things.

When you grow up as I did in Louisiana, there were very few immigrant families or any first-generation parents and you’re kind of going up against being an “other,” whether you’re an other ethnically, culturally or religiously. Whereas in Bird’s case, she feels like an other because she’s interested in all these things other people don’t seem to be interested in. It really shapes who you are. So the fact that she’s from Delaware, it doesn’t matter. You can be from anywhere.

AJ: This book comes out as students and families are learning from and staying at home. How is the story fitting for this time to get lost in this universe you created?

EEK: I’ve met at this point thousands of young people from traveling and they tell me about their own life in some situations. This book explores a non-ideal family situation — it’s not that the parents don’t love their children, but they’re caught up in their own toxic dynamic that’s permeating the rest of the family. It was important so that young people who are in that kind of family can see their dynamic on the page. My hope is that families can use it as a jumping-off point to talk about family dynamics and other things mentioned.

AJ: What’s something surprising readers may find in the book?

EEK: The teacher, Ms. Salonga, in “We Dream of Space” is never explicitly mentioned to be Filipina American but a lot of Filipinos have written to me to ask because she has a Filipina name. For the audiobook, which is read by Ramon de Ocampo who also narrated “Hello Universe,” I didn’t speak to him before he read it. But when I listened to the audiobook, he speaks in a Filipino accent doing her sections, which I love!

AJ: Advice for aspiring writers and storytellers?

EEK: My advice is definitely to read — a good writer is a good reader. It sounds kind of cliché but just keep writing because like with anything, it’s practice. That’s how you perfect your craft.

AJ: What are you reading right now?

EEK: I am in between books. I just finished a book called “The Blackbird Girls” [by Anne Blankman], which is very good. Now I’m trying to figure out what to read next. I read about two to three books a week.

AJ: There are so many options out there, especially in Filipino American literature alone coming out from major publishing houses.

EEK: Oh yes. Most notably, Randy Ribay’s book “Patron Saints of Nothing” was a National Book Award finalist and was on all these lists. I know the landscape for not just Filipino authors, but people from all kinds of marginalized groups, has opened up and will continue to do so because literature needs to reflect our entire society. That’s what our world and bookshelves should look like.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.