“It was almost like committing suicide for an African American to go to the courthouse in the Delta of Mississippi or the Black Belt of Alabama and declare his or her intention to register to vote. White organizers were risking their lives trying to register black Americans to vote. Segregationists saw the cameras of reporters, their pads and pens, as an invitation to brutality. OUR homes were bombed and our jobs were threatened. Some of us were expelled from college or run out of town. Peaceful, nonviolent protesters were trampled by horses, struck with bullwhips, beaten with nightsticks, arrested, and taken to jail. Some were shot and even killed, but we buried our dead and kept on coming. We knew we would not stop; we would never turn back until we tore down the walls of legalized segregation. We didn’t have a cell phone. We didn’t have a website. We didn’t have a computer or even a fax machine, but we used what we had. We had ourselves, so we put our bodies on the line to make a difference in our society. We were just ordinary people with an extraordinary vision, imbued with the discipline and philosophy of nonviolence.” — Rep. John Lewis, Road to Freedom: Photographs of the Civil Rights Movement, 1956-1968, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, 2008.

It was July 2016 when I saw Rep. John Lewis at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia.

I approached him and told him that I am a grandmother who came from Los Angeles. He quickly stood by my side, stopped his aide from distancing me, and the aide graciously took three photos.

His generosity of spirit resonated with me to this day that a poetic photo, taken by John Bazemore of the Associated Press, of Lewis’ casket as it crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in a horse-drawn carriage during a memorial service on July 26 in Selma, Alabama got me sobbing.

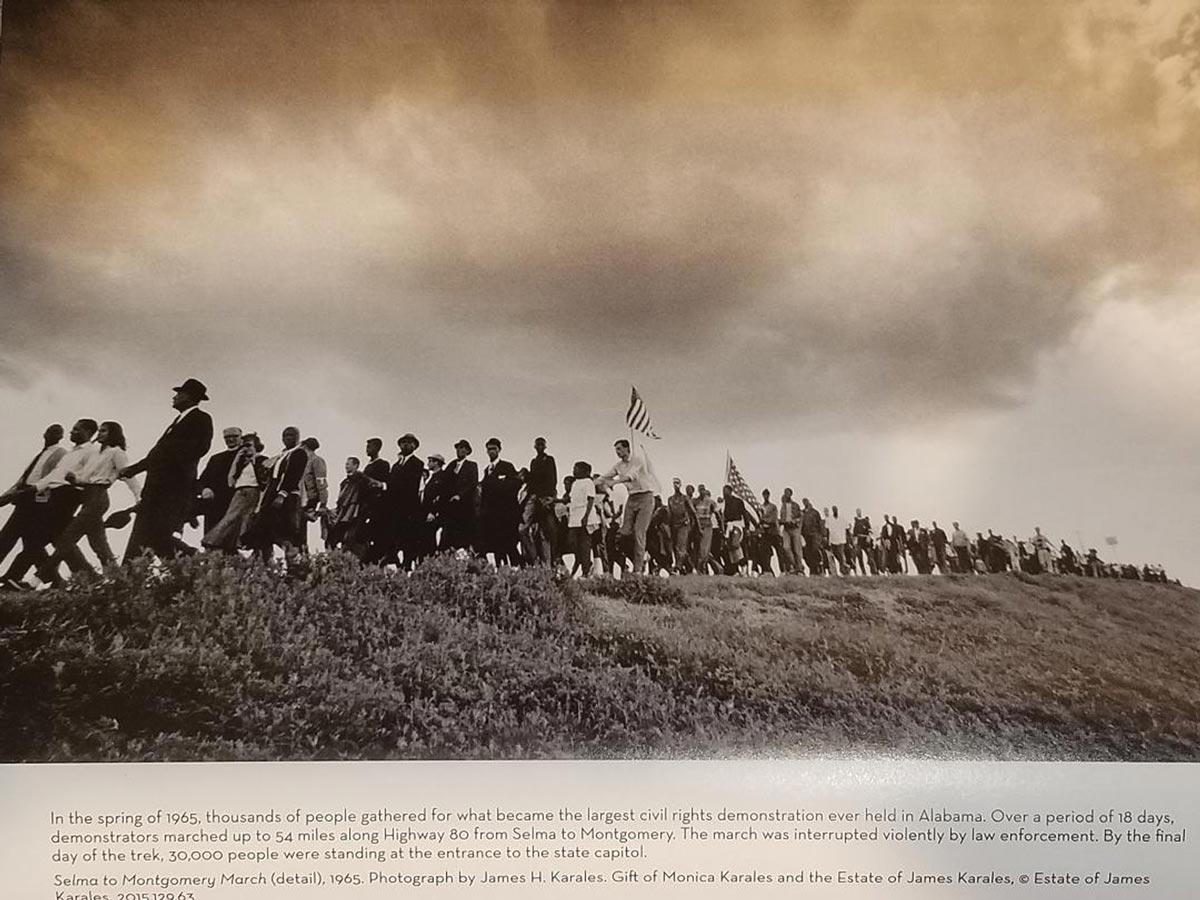

Lewis was 25 years old when he had the raw courage to lead some 600 protestors over the bridge to advocate for the right of African Americans to vote. In his own words: “it took nothing short of raw courage for participants in the movement to stand up to the governor, to the citizen’s council, to mounted police, tear gas, fire hoses, and attack dogs. It was dangerous—very dangerous—for anyone to say no to segregation and racial discrimination simply by taking a seat at an integrated lunch counter or on a public bus.”

Sydney Trent of the Washington Post’s on July 26 described how Lewis was “first to be beaten in the clash with state troopers, who cracked his skull with a billy club on the date that became known as ‘Bloody Sunday.’”

The violent beatings were seen by a dozen legislators in Congress who spoke about this state-sponsored violence: “I have just witnessed on television the new sequel to Adolf Hitler’s brown shirts,” one anguished young Alabamian from Auburn wrote to The Birmingham News. “They were George Wallace’s blue shirts. The scene in Alabama looked like scenes on old newsreels of Germany in the 1930s.

Two months later, that state-sponsored violence led to an enraged nation calling for the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Selma to all cities in the U.S.

As if mimicking 1930 and 1965, we are presently seeing in 2020, the tear gassing and baton-whipping by unidentified military personnel in Oregon attacking demonstrators who are participating in Black Lives Matter rallies.

Moms, dads and disabled veterans formed the front lines to protect the inner core of protestors.

Nationwide rallies followed after the death of George Floyd at the hands of police officer George Chauvin. The New York Times reconstructed a timeline of videotapes from bystanders, which showed that Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck, and in one frame, an anguished Floyd and the scorn in the face of Chauvin are indisputable. Floyd summoned his mother and uttered “I can’t breathe” 20 times — 20 times that Chauvin, and even the other police officers at the scene, could have stopped himself from taking Floyd’s life.

Many moms have interpreted that as Floyd calling them to rebuild a new culture of solidarity, that we all belong as God’s beloved children.

Chauvin and the three other officers were later arrested, after nonstop protests demanded their arrests, while a state-sponsored autopsy pronounced Floyd’s death might have been caused by other factors, other than police brutality.

What influenced millions of people to join the protest rallies in over 2,000 cities in over 60 countries globally in support of Black Lives Matter? Was it the tainted history of brutality towards Black Americans in this country?

From virulent racist to an American culture of solidarity

I saw the exhibit, “Breach of Peace: Photographs of Freedom Riders,” by Eric Etheridge in April 2010 at the Skirball Museum in Los Angeles. He took photos of young black men and women inside a burning Greyhound bus on May 14, 1961.

“That day, May 14, 1961, was a quiet Mother’s Day in Anniston, Alabama, described by the companion Road to Freedom book: “A Greyhound bus traveling from Atlanta to Birmingham, carrying fourteen passengers (including reporter Moses Newson, covering the Freedom Rides from the Baltimore Afro-American) pulled in to the terminal, where the station doors had been locked shut. The bus was immediately set upon by a mob led by a local Klansman named William Chappell, its tires slashed and windows smashed. There were no police in sight.

After 20 minutes, police arrived but the bus driver, O.T. Jones, was escorted to the town limits, leaving the vehicle at the mercy of another mob. As passengers were trapped inside, the bus was forced off the road by a convoy of cars for six miles, stormed by the mob, and subsequently firebombed. Postiglione captured what happened and it was not until decades later, that the images were sold to AP and UPI.

A young 12-year-old girl Janie Miller offered water to these passengers, even as she was taunted by the Klansmen to stop. Her kindness was met by more threats until her family had to leave and seek refuge elsewhere. When the black bus riders went to the local hospital, doctors refused to treat them.

“They were eventually rescued in the dead of night by a squadron of cars sent by Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, pastor of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.”

The exhibit’s photos showed dogs unleashed on Blacks, Clorox bleach poured into the swimming pool while a Black woman swam, with fire hoses directed at her.

Many Blacks were lynched and hung on trees pursuing freedom. Homemade bombs were set off in black homes and churches by the Ku Klux Klan.

On Sept. 15, 1963, four girls were killed: Addie Mae Collins, 14 years old; Denise McNair, 11 years old; Carole Robertson, 14 years old and Cynthia Wesley, 14-year-old and 14 injured in a bomb blast at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, as reported by CNN.com.

Two hundred church members with some attending Sunday school classes before the 11:00 a.m. service were inside the Church.

The bombing of the Baptist Church was the third in 11 days. Alabama Governor George Wallace responded by deploying 500 National Guards and 300 state troopers to the local city, already armed with 500 police officers and 150 sheriffs’ deputies, increasing further the volatile temperatures at that moment.

It was not until May 16, 2000, when a grand jury indicted Bobby Frank Cherry and Thomas Blanton with eight counts each of first-degree murder. Cherry was found guilty after two years and was sentenced to four life terms. On Nov. 8, 2004, he died in prison.

A week after this exhibit, I went to California’s African American Museum where a prototype of a boat that transported slaves packed like sardines in its lowest deck is displayed. I went inside to feel what it was like and I saw the chains and the dog collars used. How inhumane could that be?

“I appeal to all of you to get into this great revolution that is sweeping this nation. Get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village, and the hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes,” Rep. Lewis implored.

That includes us, Americans of Filipino descent.

Back then, Voting Rights were not recognized for all Americans, and for a long time, only white Americans were considered citizens. The Naturalization Act of 1790 defined American citizenship as limited to only “free, white persons.” Armenians who came in this early period were designated whites and gained citizenship with the help of anthropologist Franz Boas.

With blood spilled, lives lost, men and women lynched, beaten up skulls and bodies, do we now understand that our voting rights come from the sacrifices of our Black brothers and sisters?

The false legend of “all that is white is right, black is whack”

Are we conscious enough to recognize that racism is like an octopus?

That it moves below the ocean surfaces of our minds, with unexamined beliefs and unconscious gut reactions?

Do we go so far as to claim that we are not racists, yet uncaring in Blacks losing their lives to the police, even with no provocation and without threat to life, liberty, and property?

Like an octopus, racism rears its ugly tentacles of racial animus, the outright showing of hatred towards Blacks, based on the color of their skin.

That animus leads to malice when Black individuals are framed for wrongdoings and scapegoated for blame, robbing them of their most fundamental right to be respected.

An animus leading to malice followed by intentionally favoring and accruing privileges for whites, justified by a belief that they naturally belong in America.

They are welcomed to sit at the decision-making table, entitled to unearned privileges. It is an invisible backpack of privileges, handed down from generation to generation, to Whites only, leading to a culture that showcases predominantly Whites in public squares and cultural spaces, assuming dominance in film, art plays, musicals, theater, schools, universities, clinics, hospitals, industries, foundations, non-profits, media and government.

On July 26, Rep. Lewis’ casket was horse-carriage driven one last time crossing over the Edmund Pettus’ bridge in Selma, Alabama.

Thousands braved the Coronavirus pandemic’s risk to pay their respects, while shouting out loud, “I love you,” “We love you.” The majority were wearing masks.

Can we perhaps consider the belief that Lewis articulated: “Central to our philosophic concept of the Beloved Community was an affirmation of faith in humanity – the willingness to believe that man has the moral capacity to care for his fellow man. When we suffered violence and abuse, our concern was not for retaliation. We sought to understand the human condition of our attackers and to accept the suffering in the right spirit. We believed that ends and means were inseparable, so we wanted to create a peaceful society, then we had to use the methods of peace and goodwill. Our protests were love in action. We were attempting to redeem not only our attackers but the very soul of America.”

Much like Rep. Lewis’ casket crossed the Edmund Pettus’ bridge, can we as Filipino Americans and Asian Americans, have the courage to be part of the solution, of redeeming the soul of America, solidifying our ties to Blacks and challenge the evil of racist animus to not be in our midst?

But more than that, as American citizens and future citizens to be, it is in our hands to create a more just and peaceful America by exercising our votes, choosing better representatives who will work not just for a mighty few 1%, but mostly assist small businesses to grow, for working labor to be paid living wages that can support families and sending our children and grandchildren to college, a valuable Filipino family value of improving each generation.

“Though I may not be here with you, I urge you to answer the highest calling of your heart and stand up for what you truly believe. In my life I have done all I can to demonstrate that the way of peace, the way of love and nonviolence is the more excellent way. Now it is your turn to let freedom ring,” Lewis wrote in an OP-ED in the New York Times on July 30, 2020.

He sent it two days before he died from pancreatic cancer on July 15 and requested it be published on the day of his funeral.

* * *

Prosy Abarquez-Delacruz, J.D. writes a weekly column for Asian Journal, called “Rhizomes.” She has been writing for AJ Press for 12 years. She also contributes to Balikbayan Magazine. Her training and experiences are in science, food technology, law and community volunteerism for 4 decades. She holds a B.S. degree from the University of the Philippines, a law degree from Whittier College School of Law in California and a certificate on 21st Century Leadership from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. She has been a participant in NVM Writing Workshops taught by Prof. Peter Bacho for 4 years and Prof. Russell Leong. She has travelled to France, Holland, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Japan, Costa Rica, Mexico and over 22 national parks in the US, in her pursuit of love for nature and the arts.