“WHEN I was growing up, my mom would always say: ‘You have to be better than us.’ She never explained what she meant by that. But I understood. I had to somehow rise above my parents’ life in America. But how?”

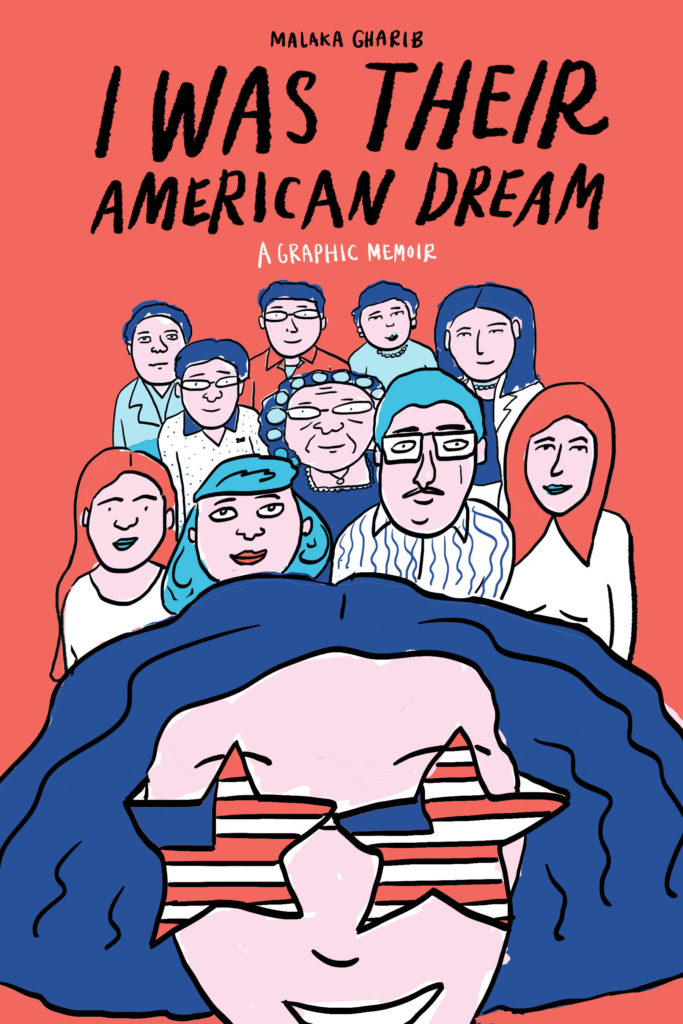

Filipina-Egyptian writer and artist Malaka Gharib explores this idea of a ‘better life’ in the early pages of her graphic memoir, “I Was Their American Dream,” which was released earlier this spring.

Through comics that illustrate anecdotes — from her Filipina mother and Egyptian father’s immigration stories to her upbringing in Cerritos, California and struggles to find a sense of belonging — Gharib goes beyond the stereotypical caricatures of what Filipinos or Egyptians are thought to look and act like and shows that there’s more to the immigrant experience than what the media portrays.

Gharib, who is the deputy editor and digital strategist of NPR’s Goats and Soda by day, was compelled to explore race and identity following the 2016 election after seeing the “anti-immigrant” rhetoric in the news.

The result: a novel inspired by a ‘90s comic book charting Gharib’s perspective in a mixed-race household through red, white and blue colored-drawings, with some pages inviting the reader to be interactive as well.

The pages take readers through trying to fit in at high school and college, summers in Egypt where her dad moved back to after the divorce, the defiance of being a writer instead of a traditional job, and teaching her husband about her multicultural identity.

Yet, with the specific details of Gharib’s personal story, a universality emerges that especially first generation kids in American can relate to, whether it’s emulating what we see while watching popular TV shows or having to balance the cultures we identify with.

In a conversation with the Asian Journal, Gharib talks about the creation of “I Was Their American Dream” and why it’s time to own our identity and culture.

Asian Journal (AJ): At what point did you want to tell your story as a Filipina-Egyptian growing up in America?

Malaka Gharib (MG): I never really thought much about race issues that deeply until 2016 and seeing all the anti-immigrant rhetoric in the news. The very one-dimensional conversations that I was seeing in the media about immigrants — that we were coming here and taking people jobs, that we were terrorists — did not really match with what I grew up with in Cerritos, California. I grew up in a town that was an Asian bubble and had a lot of diversity and people from every social class. I also had my parents’ own story, which didn’t match the news either. Thinking about my dad, for example, he’s Muslim. I was a little too young for the post-9/11 discourse about Muslims, but for some reason, 2016 seemed to be the moment because I was an adult by then and I thought about my dad who liked gardening and loved the movie ‘Forrest Gump.’ He’s totally harmless. I wanted to correct the narrative that I was seeing and provide my own nuanced perspective for readers and also my generation.

AJ: How did you decide a graphic novel would be the best platform for doing so?

MG: As for why the graphic novel format, a big part of my artwork is the zine and comic book culture…I would buy zines at Skylight Books in LA and then try to create my own zines and comics at home and get them printed at the copy machine at my uncle’s medical office in Historic Filipinotown. That was a very foundational way for me to express myself. There wasn’t a question in my mind that I wanted to emulate this diary feel, DIY-style in expressing myself in the book.

AJ: How did this idea become a book deal?

MG: My publisher is Clarkson Potter, which is an imprint of Penguin. I was making stuff and posting it on Instagram. I think I had less than 30 cartoons on there when a friend of mine at NPR said, ‘Hey, my friend is an agent and you should pitch this as a book.’ I didn’t take it seriously because I couldn’t imagine it turning into a book. She was very encouraging about it and said, ‘Here’s your idea: cartoons about being a first generation Filipino-Egyptian-American.’ I think everybody in 2016 understood that there was this need for nuanced immigrant stories and that was something easy to sell to publishers during that time.

AJ: The book is a quick read but is rich with intricate detail — whether it’s your mom using a cookie tin for a sewing kit or your dad eating KFC on the couch. What was the storyboarding process like and how did you decide on what details to include on certain pages?

MG: For me, I wanted to use the least amount of information to convey the maximum story. That’s what I really love about the comics format in that it’s very restrictive. It’s like poetry: What are the base images, words and dialogue you need to tell the most impactful story? I had Easter eggs throughout the entire book too…if you knew, you knew. Everybody was like, ‘I totally eat with one foot up and the other foot down on the chair too.’ I’m so glad that people caught that because I put this little Easter egg in there. Like people who understood the sewing kit cookie tin reference — those are the little things I put in there for us.

As for storyboarding, what was it that I wanted to say on a whole? I wanted to explore my relationship to race during high school and I would then unpack that into further detail. What did I aspire to look like? Why did I think that way? Why did I think that looking that way was the right way to look? When I unpacked those questions, I tried to use anecdotes to bring those answers to life. I wanted to look like that because I didn’t fit in. Instead of saying that, I tried to think of stories. I thought about [my sister] Min Min and how she took those pictures in high school with all those Filipina girls next to her…I never got to do anything like that because I didn’t have a group of Filipina girlfriends because I didn’t pass as one.

AJ: How reliant were you on past diaries and drawings?

MG: I relied on them pretty heavily. I kept a very serious journal in high school and college and even in my prepubescent years. I have them all at home and looked back at those in case there were any stories that were missing, but I also fact-checked my own history by calling elementary, high school and college friends.

AJ: What conversations did you have with your family and friends? I know you spoke to your mom and dad about telling this family history.

MG: I tried to use a journalist framework, which is you should never let your subject be surprised when they read the final story. You should be giving them clues along the way as to what the story is about, if it’s going be combative or supportive. In the question, they should be able to infer the tone and content of the story. I asked my parents questions like, ‘Why did you and dad get a divorce?’ ‘Dad, why did you get so upset when I told you Darren was going to be my husband? Do you feel okay with people knowing that?’ I tried to be very fair to them and give clues to my family members about what the story was going to be about.

AJ: Were there any memories or instances growing up that you wanted to include but didn’t end up because of page constraints?

MG: Absolutely, that’s a great question and haven’t gotten that one before. I wanted to explore the conflict in religion. I think that when you’re growing up in a really devout household, religion is so important and you take it as seriously as your parents. When you’re young, you don’t question religion then and you believe the stories they tell you. You believe that two angels are on your shoulders watching your every move and you believe in heaven and hell and are guided by that righteousness. I wanted to talk about more deeply when I lost my faith in Catholicism, which was around the time I got confirmed. We went on this retreat in Big Bear and it was weird and cultish and I felt really uncomfortable. They made us kneel around in a circle and they said they would bring Jesus out at any second but they made us pray for an hour and when they finally brought Jesus out, he was a candle. I was so mad. It confirmed to me that I was better off as a Muslim anyways in the end.

I wanted to include that story in the book because I think that religious pressure is such a big part of the immigrant experience too. I had limited space and also, I had a great editor named Kat Chow, who is one of the founding members of NPR’s Code Switch podcast. I hired her to help guide me in the process of helping me explore my race and identity issues. She basically said, ‘You can’t fit everything in. You just have to unpack a few things.’ I let that one go but that was something I really wanted to go into.

AJ: The pages where you compare praying in a Filipino Catholic household versus the Egyptian Muslim household and the contradictions were interesting. Do you still feel that pressure of being on top of the customs and language when you’re with your sides of the family?

MG: Oh yeah! My dad and a lot of my Arab family are on Instagram and there are a lot of things I just don’t post. I don’t post photos of me smoking hookah or me eating during the month of Ramadan…out of respect of my family members. I don’t post overly provocative clothing because it’s very conservative in the Middle East and I don’t want my family to get the wrong idea about me.

AJ: Growing up what were some of your favorite books or authors who inspired you to be a writer and journalist?

MG: This is a very cliché thing but Tatay [maternal grandfather], when I was growing up in the 8th grade, he gave me a copy of ‘The Catcher in the Rye’ and it was a very mature, introspective, moody, coming-of-age story…I probably read it six times through the duration of high school but I really loved the poignant sensitivity and care of Holden Caulfield. I wanted to emulate that in my writing style too. Comics and zines too, but I didn’t get into reading longer form or mainstream ones until after college. I read a lot of indie ones but I don’t even remember the titles of them. I was also really moved by the American Girl books. I like wholesome things in general, which is why the book, you could argue, can be perceived as wholesome and appropriate for young adults. I liked the historical stories about the girls, learning about their lives and cultures, and how they shaped them and their view of the world. I always wished they would have a book for a Filipino Egyptian so I tried to think about writing one.

AJ: You spend your time at NPR writing about poverty and global development. But you’ve written pieces about your Filipino culture, whether through food or your husband wearing a Barong to your grandfather’s birthday. What was it like pitching those stories to your editor at NPR and having that platform to talk about your identity on a mainstream scale?

MG: I am very lucky to be at a place where I can have such a huge platform…I did a piece about the Filipino lunch club we had and one about mental health and I did one recently about Thanksgiving…and an interesting perspective for the mainstream to see that other cultures just don’t eat turkey and mashed potatoes. I feel this obligation to write about stories I’m passionate about. I’m always thinking about the people I grew up with in Southern California, what they might be interested in reading because I am them and I am interested in reading that stuff too.

AJ: You have some anecdotes around the question of ‘what are you?’ In the book, you write ‘I used to love this question because it gave me the opportunity to talk about my ethnicity. But not everyone felt that way.’ How have you come into your identity over the years?

MG: There’s no better time than now to proclaim from the rooftops your ethnicity. If this how you identify yourself and you are proud of it, then why should we hide that? There is something so beautiful about representing your culture…For a little bit, I didn’t want to tell people who I am but now, I want you to know exactly who I am and I want to celebrate my ethnicity.

AJ: Through this journey, what does it mean for you to be Filipina?

MG: My whole life, we were taught that being Filipino was a bad thing. In high school, I went to school with a lot of other Asians but I quickly understood that Filipinos were at the bottom of whatever hierarchy of the Asians with the Japanese at the top. When I would go to Egypt, my dad would tell me not to tell others that I was Filipino because, in the Middle East, Filipinos are the help. I had thought it wasn’t an honorable thing to be Filipino, but now, I get so excited when I see another Filipino out in the world. It’s a time to celebrate each other and it has lifted my heart in so many ways.

AJ: What do you want readers to take away from “I Was Their American Dream”?

MG: First of all, I hope people can relate to this book who aren’t Filipino or Egyptian. What I’ve been amazed by is that so many people have found it relatable. It’s not just Filipinos who are reaching out and saying thank you for writing this book. It’s been people from so many countless cultures. I’ve seen the book become a force to bring people together like I saw a post of a group of young people having a kamayan dinner and said they were inspired by the book to have the dinner and talk about being Filipino. Someone told me, ‘This book makes me want to call my grandma and celebrate everything that we are.’ I want people to be proud of who they are. No matter who you are, take pride in it. There’s nothing to be ashamed of and you don’t have to try to be something that you’re not.

AJ: In this book and even in your other writings and posts on social media, you share a lot of yourself. What’s something people may not know about you?

MG: I actually don’t find the things I share too personal. I feel like the stories are so universal that they’re impossible to be truly personal. I hope that makes people more vulnerable. In this world where everything’s so fake and posed, you’re constantly being promoted at by ads and everything is so algorithmically chosen for you so I want there to be some vulnerability, kindness, personal connection and intimacy. I hope the things I make bring people together or a person closer to how they’re feeling.

AJ: For you, what does the American Dream mean?

MG: I never knew that I needed to have an American Dream. I only thought that American Dreams were for outsiders. But I grew up feeling like an outsider too in this country and I realized that I also needed to have a dream, which was weird. But it wasn’t like my parents’ dream of a white picket fence or buying all my titos some polo shirts from the outlet. Mine was to feel a sense of belonging in my own country — the country that my parents told me I belonged in, yet it hadn’t felt that way.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.