By Alice Sarmiento, NextDayBetter Storytelling Associate

For many of us, school is like a home away from home, with our teachers acting as our parents. But in the United States, an ongoing teacher shortage is threatening these definitions.

In 2018, it was estimated by The Learning Policy Institute that the country was lacking at least 112,000 teachers. To avert this crisis, some school districts resorted to hiring teachers without proper licenses or taking in long-term substitutes. Some rural areas, however, are hiring teachers from abroad through placement agencies, many of which are located in the Philippines. Today, over 500 public schools in at least 19 states have employed Filipino teachers on J-1 visas.

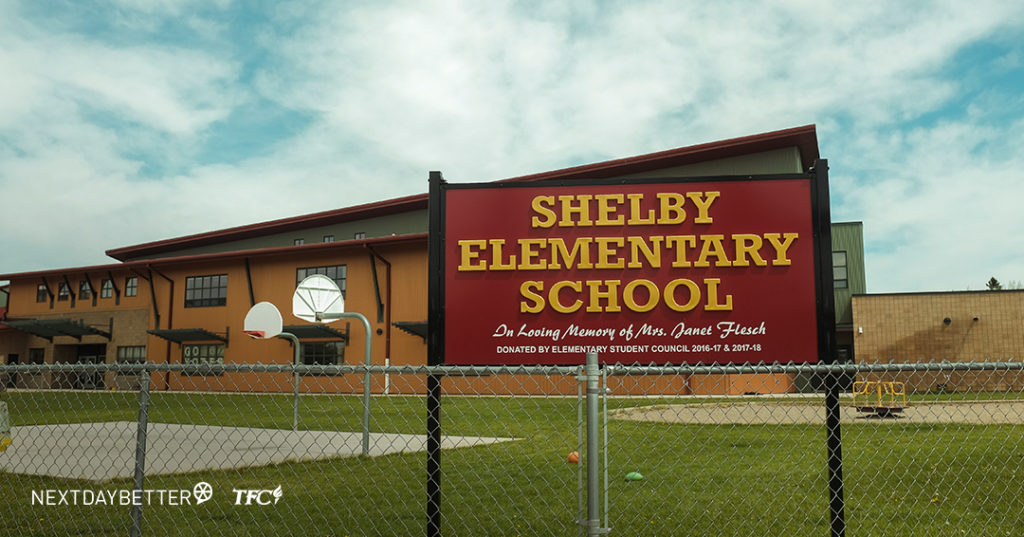

Teachers like Mary Manda, who was recruited to teach children with special needs in Shelby, Montana, are issued a J-1, or exchange visitor visa. For teachers, the program promises educational and cultural enrichment, where according to the official website they “sharpen their professional skills and participate in cross-cultural activities in schools and communities, and they return to their home school after the exchange to share their experiences and increased knowledge of the United States and the U.S. educational system.” The problem lies in the very name of the program under which this visa falls: as exchange visitors, teachers are only allowed to work in the US for a maximum of five years.

“How are we going to help them if our contract will not be continued?” Manda asks. While teachers are allowed to repeat the program, provided they reside outside of the US for at least two years before returning, this will come at the cost of starting over, along with every risk that entails.

“We’ve put a lot of time and effort into helping them come to Shelby to be a part of our community,” says Elliot Crump, who is the superintendent of the school district. While Crump is aware of the time-bound conditions of the J-1, Manda’s looming departure has forced him to reflect on the profound implications of teaching as temporary employment.

“If you have skilled people coming to the United States doing a fantastic job, why aren’t they staying? Why isn’t there some sort of a path to allow them to stay, continue to work with my kids, continue to have positive outcomes for the country as a whole?” asks Crump.

The dependence of school districts on using the J-1 program sheds light on how teachers–and maybe the education system as a whole–are viewed. It shows how teachers are expected to perform the kind of job that requires passion, care, and belonging. And then they are expected to leave as if to teach was a simple transaction, or in the terms of the J-1, an exchange.

The bigger question is, if teachers play a valuable role in educating the next generation of citizens, then why are so many are denied citizenship by being subjected to these terms?

Immigration lawyer Rio Guerrero paints this reliance on the J-1 as a problem of commitment. He posits, “The J Visa program brings the brightest Filipino teachers. But they can only be fully committed if we commit to them.”

A more desirable alternative, in this case, would be the H-1B or specialty employment visa. Holders of the H1-B are granted permission to work in the US for three years, after which they may apply for an extension of three more years, adding up to a total of six years. The biggest difference is that H1-B visa holders may, in their fifth year of employment, apply for a green card or permanent residence visa.

For now, the clock is ticking for teachers like Manda and soon it will be time to say goodbye. While superintendents like Crump can still recruit new teachers to take her place, they are well aware of the consequences of this loss for the children of Shelby. For Crump, the ease of navigating the systems that allow him to hire someone new simply cannot compare to the difficulty of starting over, both for Mary Manda and for the children she had committed to serving.

Guerrero agrees. “I want my children’s teachers to be fully committed to their education and our community,” he says. “We should correct US immigration law to allow J Visa teachers to become green card holders.”