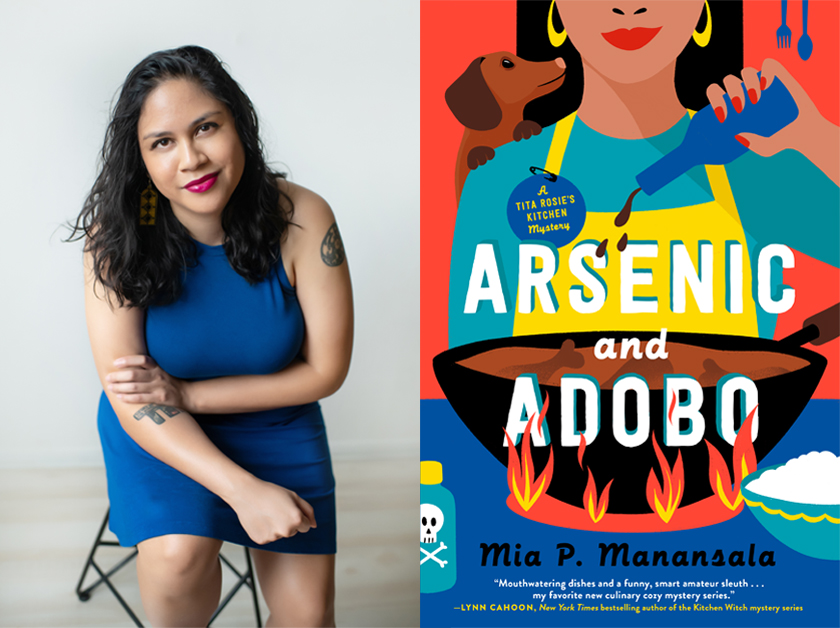

Photos courtesy of Jamilla Yipp Photography and Berkley/ Penguin Random House

“MY name is Lila Macapagal and my life has become a rom-com cliché.”

The opening lines of “Arsenic and Adobo,” the debut novel from Chicago-based author Mia P. Manansala, read like a typical romantic comedy.

The leading lady, who this time happens to be a Filipina American named Lila Macapagal, moves back to her suburban hometown of Shady Palms, Illinois after breaking up with her cheating fiancé. To fill her days, she pitches in to help her Tita Rosie’s struggling Filipino restaurant and “in the trope of all tropes,” she reconnects with Derek Winter, her high school sweetheart.

Though Derek is now a vicious food critic who has beef with Tita Rosie’s restaurant and on the day he comes in for a meal and has a confrontation with Lila, he drops dead on top of the food.

It becomes an Agatha Christie-type case in which Lila, who is the one and only suspect, must use her amateur sleuthing skills to piece together what happened and how exactly arsenic got into Derek’s system. In the novel’s some 300 pages, readers meet the many characters in Lila’s Shady Palms life, from her Dachsund named Longanisa to her band of nosy titas dubbed “the Calendar Crew.”

True to the culinary cozy mystery subgenre, “Arsenic and Adobo,” which will be released on May 4 (Berkley/Penguin Random House), features recipes, including Lila’s ube crinkles and Tita Rosie’s chicken adobo.

Manansala’s highly-anticipated novel is the first in the “Tita Rosie’s Kitchen Mystery” series, so expect more captivating stories that tie in her experiences as a Fil-Am in the diaspora and of course, food.

For the author, writing and the influences that would lead her to a path of mystery and crime fiction were present early in her life — from watching crime dramas like “Murder, She Wrote” and “Matlock” with her grandparents and reading the “Encyclopedia Brown” series. She even won an elementary school award for her reimagining of the “Three Little Pigs” that involved the Big Bad Wolf as a drug dealer.

But it wasn’t until 2015 when Manansala took her first mystery writing workshop in Chicago after spending almost four years teaching English in South Korea. Her early writing garnered several accolades, including the 2018 Hugh Holton Award and the 2018 Eleanor Taylor Bland Crime Fiction Writers of Color Award.

In an interview with the Asian Journal, Manansala spoke about how she developed her debut novel with a Filipina protagonist and pieces of her culture and is carving out space in the culinary cozy mystery genre.

Asian Journal (AJ): At what point in this writing journey, did you create the story that would eventually become ‘Arsenic and Adobo?’

Mia Manansala (MM): This is actually the second book. What I wrote during the workshop was the first novel I ever finished. It won some awards for unpublished writing and it got me into a mentorship program with my wonderful mentor, Kellye Garrett, who has also helped me a lot along the way. It got me my first agent, but it never sold even though it was trying to be sold to editors for about a year and a half. At that time, I was like, ‘Well, I need to start working on the next thing.’

AJ: What was the plot of that novel?

MM: It was a queer Filipina American woman solving a murder mystery at a comic book convention. It was a lot of fun and the feedback was, in general, the same: ‘The writing is so fun. We like this world. We can’t sell it.’ They said there was no market for it. I didn’t purposely write a more ‘marketable’ book, but cozy mystery, which is the genre ‘Arsenic and Adobo’ is in, is a sub-genre that I’ve always loved. It’s my mom’s favorite and she’s the one who introduced me to this particular subset of mystery.

I knew I needed a new project so one day when I was talking with my mentor, Kellye, we were making jokes about how in this particular subgenre a lot of the tropes are similar to romcom, which in the whole first page is me playing with that. I was riding the train to work and the first line popped into my head fully formed that with the character, full name and everything: “My name is Lila Macapagal and my life has become a rom-com cliché.” That’s been the first line the entire time. I started it in 2018 and it’s being published now three years later and those opening sentences have never changed.

AJ: What was the process of developing Lila and her whole world in Shady Palms. We meet a lot of different characters along the way.

MM: Lila originally started as an exercise, almost like an alternate version of me. I grew in a majority Latinx working-class neighborhood in Chicago. I grew up in a multi-generational household like she did. We lived with my maternal grandparents, parents, brothers so we did have that kind of family dynamic. But I didn’t have a Filipino community necessarily in the larger sense. My parents’ friends and family friends, like my godmothers and godfathers, were out in the Chicago suburbs and were a little bit more well to do than us — not super wealthy but at least middle class or upper-middle class. So when I would go to these Filipino family parties, I would wonder, ‘How different would my life be? How different would my outlook be if I grew up in the suburb where it is majority white but I also have this extended Filipino family and community available to me?’

I think I brought about this feeling of being a big fish in a small pond. Even though it’s completely different circumstances, different settings, I started from there and then tried to figure out who would this person be: this 25-year-old girl, small town, had her dreams crushed, and is trying to pick up the pieces again.

AJ: The whole plotline is her ex-boyfriend, a food critic, who dies at the restaurant. How did that become the center of the novel?

MM: I was playing with the tropes and expectations of both — this rom-com idea of her coming back home and reconnecting with her first love was me having fun, but wait, this is a mystery. She reconnects with this guy, but he’s a jerk who’s been trying to shut down her family’s restaurant and he dies in said restaurant. She now has to clear her name and save the family’s reputation. That was something I knew from the very beginning because it’s a restaurant and he’s a food critic so naturally, how would that come about? He couldn’t be found with a knife in his back or a gunshot wound because that wouldn’t tie into Lila and her story there. But the ‘how’ of the poising — that part’s not a spoiler because it’s in the title — and the why and when took more time to work out.

AJ: We have to talk about the ‘adobo’ part of this novel. What did you want to portray about the Filipino American identity or experience? There’s no clear picture or one way of what it means to be Fil-Am, obviously. What did you want to share about our culture and this experience knowing that this book is going to be read vastly beyond our community?

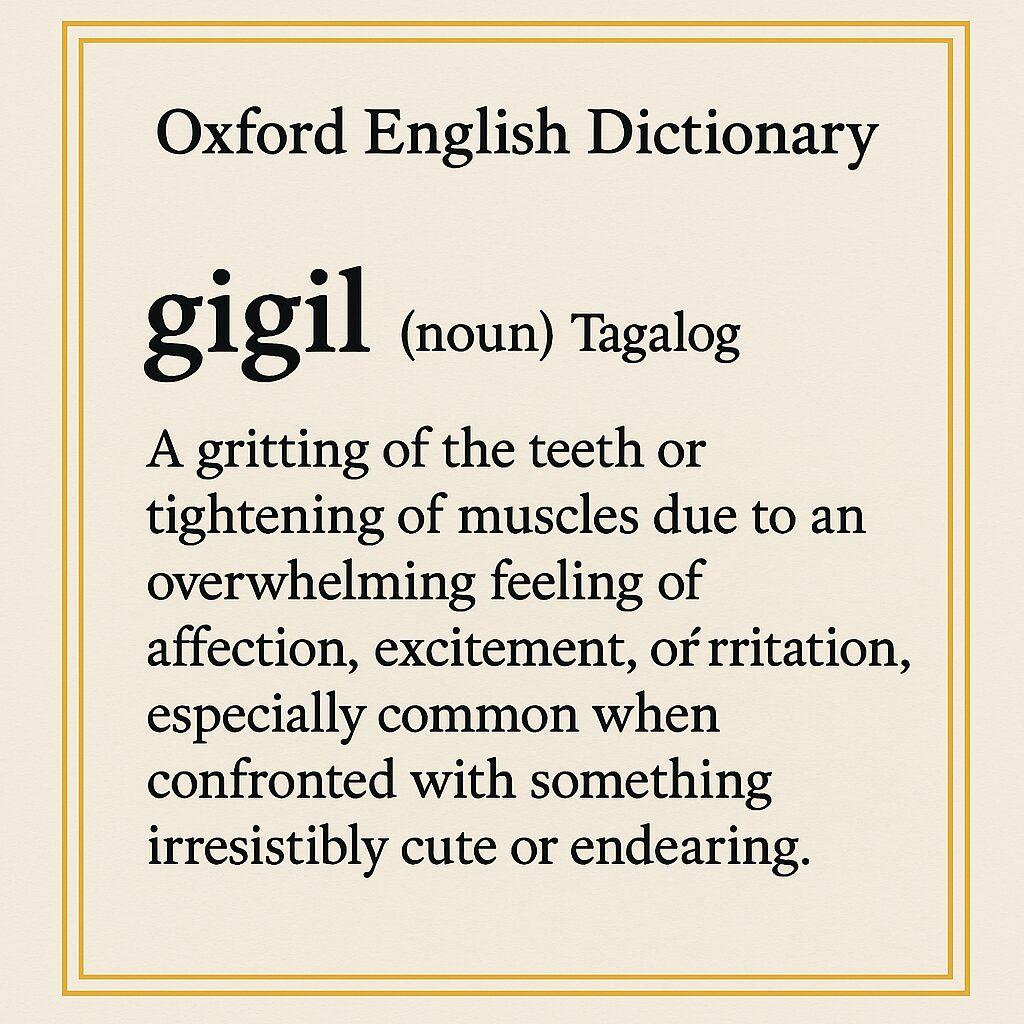

MM: The ideas of how family and community are so important, especially being in the diaspora, that push and pull because I was born and raised in Chicago. I don’t speak Tagalog, but I can understand it. I didn’t have the ‘community’ growing up but I had my family, which is super important to us. There are also generational divides and diaspora divides and one is not necessarily right or better than the other. If you are born and raised here, the idea of independence is kind is culturally ground into you, but that clashes with your ethnic upbringing where it’s about family, the good of the community, and watching out for everyone. But how can you live for your family while still pursuing your own wants, dreams and desires in a way that feels selfish to other people?

I also wanted to show that we are not a monolith. I would never want anyone to look at this and be like, ‘Yes, look at her as THE Filipino American voice.’ No, I’m not even the Filipino American voice of Chicago. My experiences are so personal to me. There’s no one way to be Filipino. I think so many of us, especially diaspora, question: What does that mean? Am I Filipino enough? Can I write these stories? What does identity mean if have only been [to the Philippines] a handful of times and can’t speak the language?

AJ: You mention a sensitivity reader in the author’s notes.

MM: I mentioned a homeland Filipino, someone born and raised and currently living in the Philippines, who read it because I have some Tagalog phrases in there and I wanted to make sure that the language made sense. There are some immigrant characters and I’m not an immigrant. Particularly for the lola character, Lola Flor, I didn’t want her to be this inflexible villain or flat and one-dimensional despite her being the one Lila butts heads with the most. I wanted to fully understand why would she be this way that is super frustrating for Lila and for me growing up with my grandparents. That sensitivity reader was able to give me some perspective, especially when it came to the idea of traditional food.

AJ: The sensitivity reader also brought up the current drug war in the Philippines. How important was that to include in the author’s note and have that before people even dive into the book?

MM: I hired her specifically for the more cultural and language things and then when she pointed that out, she told me that was extremely triggering for her. She literally put the book down and walked away that day because she was so unprepared for it. I had a very American perspective and mystery writer’s perspective following the tropes of mystery. That’s why an amateur sleuth acts because the police are corrupt or just not great at their job. If you were a regular mystery reader, you’d expect that kind of thing.

But then I realized, what is kind of magical about this, is that not only mystery readers will be picking up this book. I’ve been getting lots of messages from people who are saying, ‘Mystery is not really a genre I’m into, especially not cozy mystery, but I’m so excited that there’s a Filipino protagonist’ that they’re picking it up anyway. These are people again who are not cognizant of these tropes that I would hate for them to think it looks fun, light and humorous and then you go in, and then you’re just triggered by certain things.

You can only prepare people so much. Obviously, I can’t change how people react to it but I want to let know that if there are certain things that are traumatic for you, I don’t want you to be surprised because you wanted some light, happy pandemic reading because you can’t handle anything else. I want also international readers to pick up my book and enjoy this oddly specific Midwestern, but still hopefully universal story.

AJ: How did food play into the writing?

MM: When I first sold the sold story, I had a different title: ‘Love, Loss and Lumpia.’ I was originally going to make lumpia more central, and then my editors were correct in stating that while it’s a great title, it doesn’t really read mystery. They wanted a title that made it obvious what kind of genre it was. Out of the list I gave them, they chose ‘Arsenic and Adobo,’ which is a really good starting place since adobo is considered our national dish. I did some revising based on this title, based on the fact that arsenic was being brought in and that adobo was highlighted food in the title.

Some of it was me trying to show what kind of people these were and the relationships, like Lila’s best friend is vegetarian and her family is Muslim. Filipino food can be very meat-heavy, and particularly pork heavy, so I wanted to show how thoughtful Tita Rosie was and food is love and care for her in the way she goes out of the way to find meat substitutes or make vegetarian dishes. Same with Lola Flor, her being a little bit inflexible does show how she is still trying to hold on to part of her past and that her homeland is still something she’s proud of. It’s never just food on a plate for this family.

AJ: ‘Arsenic and Adobo’ is the first in a series. What’s next for you?

MM: Currently I have a three book deal with my publisher Berkley. Fingers crossed that this does well and they want more books in the series. The way it works is that it’s the same characters, same town and world, but each book can technically be a standalone. It’s not an overarching plot the way you would see in a fantasy series. Each book is its own crime.

Book two takes place in the summertime and centers around a teen beauty pageant because Filipinos, small towns, beauty pageants — that’s a beautiful intersection right there. I want to tackle the love Filipinos have for beauty pageants, but a lot of the colorism and colonial and patriarchal beauty standards that are imposed not just by outsiders but by ourselves. Also, how mother-daughter relationships are complicated because Lila’s deceased mother was a beauty queen. At the center, the family and community band together to solve the crime.

AJ: Can you talk about adding the recipes at the end? With the pandemic, a lot of people started baking and it’s also another way to bring the story and Lila’s world with us and eat alongside her.

MM: With culinary cozy, which is a subgenre of cozy mystery, most of them, not all, have recipes. The idea of having recipes was always in mind and I thought being able to introduce this audience to Filipino food was so exciting. I have this long Google Doc of foods that I wanted to get to because baking is research and I was technically working as I made these delicious things. In choosing them, I knew adobo had to be a big part because it’s in the name and it’s a gateway thing. For Lila, I wanted to show her style in that she loves traditional Filipino food, but she also wants to make a twist by using Filipino ingredients and use it in an American way. With the ube crinkles, they’re super fun, delicious and beautiful to look at so I thought that’d be a really great way to introduce people to ube.

AJ: Your book is coming out May 4 and already there’s some buzz. What was it like for your book to be chosen for ‘Book of the Month,’ [a subscription service that sends new books to members]?

MM: When I found out about it, I was shocked because I think it might be the first cozy mystery they’ve ever chosen. I’m going to be very real, it was an author bucket list goal to someday have a book chosen for that. The fact that my book is reaching a readership I might not otherwise have — because again, not everyone gravitates towards mystery or cozy mystery, which usually skews a bit older in the audience — I think it’s because I have such a different, vibrant cover. People trust the Book of the Month selections so they’re willing to take a chance on something they would never have read.

AJ: How have storytelling, reading and food connected for you during this time we’ve spent at home?

MM: Like most people, food is comfort for me. Being able to test out and develop these recipes has been really therapeutic…When I was drafting Book Two, which was entirely during the pandemic, tonally, it kept getting lost because things were so dark. It was intruding into my headspace. I had to keep setting it aside because it kept going places that were not natural. That’s been the hardest thing for the pandemic. We call it Book Two syndrome because with the first book you have all the time in the world to make it the way you want. With Book Two, you’re writing on a deadline and as much as you want an excellent product, you have to turn it in when they say so because everybody has a schedule. If your book is delayed too long, that affects all the other books.

AJ: In the past three years or so, we’ve been lucky to see a lot of published authors from the Fil-Am community.

MM: When it comes to representation, we always need more. No book is everybody. Not everybody will have the same experience as me. If you’re a Filipino American and pick up this book and you’re kind of disappointed, that’s fair right? That’s valid. Maybe it wasn’t for you or maybe you had particular experiences you were hoping would be reflected. The problem is not with me or with them. The problem is that there’s not enough representation to show the scope and spectrum of all these experiences. A white person is not going to pick up a book and be like, ‘This is not the white experience.’ Never because they just have everything else they could look at. But with us, it’s so limited, that I can understand the disappointment and hoping that you finally get to see yourself on the page and then you don’t write. I just hope that you understand that it’s a creative difference and subjective. The only thing you can do is keep asking for more and demanding more for us so that we can all see ourselves.

The interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Reading the summary of this book leaves me with a sense of foreboding.