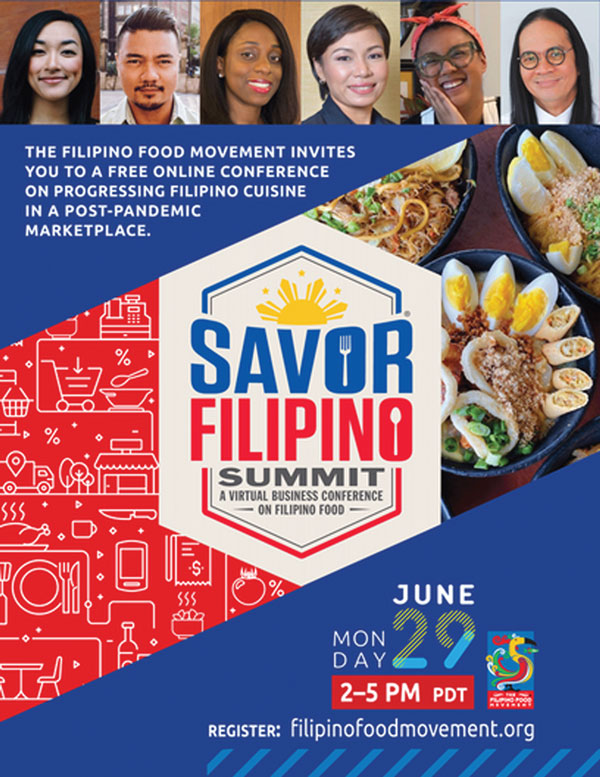

FILIPINO FOOD MOVEMENT’S ‘SAVOR FILIPINO’ SUMMIT

WITH its goal to create a framework in order to innovate the business of Filipino cuisine in the time of the pandemic, the Filipino Food Movement held a virtual summit called ‘Savor Filipino’ on Monday, June 29.

The meeting was attended by almost a hundred people across the globe, coming from different fields and industries but all share the same love and commitment to Filipino food.

“Filipino cuisine is no longer the next big thing. It is a part of the American culinary landscape,” said Department of Tourism Secretary Berna Romulo-Puyat who opened the summit.

Puyat added that the best way to promote a country is through its food and what better way to understand Filipino culture but also through its food.

The tourism secretary mentioned that they brought in three Filipino American chefs to the Philippines late last year so they could visit culinary destinations in order to learn about heirloom delicacies and heritage ingredients that they could use in their respective restaurants when they return to the United States.

Sonia Delen, Filipino Food Movement president, talked briefly about how they adjusted with the times and came up with Kulinarya Live, quarantine cooking series streamed online featuring Filipino chefs from the diaspora. The project came about when they realized that because of the quarantine, people have reignited their interest in baking and cooking.

As a nonprofit organization, FFM has been at the forefront in promoting Filipino cuisine and creating a sustainable impact on the Filipino culinary industry whether it is through dinners, outreach or gala events.

‘Dial it up’

Ligaya Mishan, the award-winning New York Times food writer and critic and writer, delivered the keynote speech along with restaurateur and cookbook author Nicole Ponseca Mishan shared a little bit of her own personal history. Her mom, originally from Cotabato City in the Philippines, married her dad who was from England. They met in Tokyo and ended up living in Hawaii.

Mishan said that as a writer, how she writes about food matters.

“I don’t use the words ethnic or cheap. I’m uneasy with ‘authentic’, too,” she said, citing the fact that recipes are not static and they tend to change based on the availability of ingredients, among other reasons.

As a writer for NYT, Mishan has reviewed and featured dozens of restaurants, among them, Filipino rests in Manhattan and Queens. She also wrote a long feature on Doreen Fernandez, the doyenne of Filipino food writing.

She echoed Puyat’s thoughts on the role of Filipino food in the American culinary landscape and said that “America has changed, particularly the way we eat now” and that Filipino cuisine is a part of the “brilliant pastiche of colors from around the world” that makes American dining unique.

Nicole Ponseca, founder and owner of Jeepney and Maharlika, talked about her own journey, including how she decided to close Maharlika in December after almost ten years of operations.

“I don’t really know what the future holds, restaurants like us are earning a fraction of what we used to make,” she said. “But we are warriors and we are going to figure out how to move on together.”

Like her colleagues in New York, Ponseca pivoted and worked on getting donations in order to send food to frontliners in hospitals across the city.

While she has been mentioned many times as the one who broke down walls when she and chef Miguel Trinidad opened Maharlika in 2010, Ponseca along with Mishan paid tribute to those who began the fight to bring Filipino cuisine to New York’s mainstream.

They mentioned Amy Besa and Romy Dorotan who ran Cendrillon in Soho and King Phojanakong who opened Kuma Inn in the Lower East Side for opening the door and the conversations that followed suit.

Ponseca, who also published a bestselling book on Filipino cuisine (and a 2019 James Beard Award finalist) called “I Am Filipino: This is How We Cook”, shared the challenges they had to hurdle in order to keep both restaurants running. Her strategy to use what used to embarrass her as a child and made them work for her.

As a teen, Ponseca said she was embarrassed when she would bring friends to her home and they would see her dad using his hands to eat. At Jeepney, she introduced Kamayan dinners, where diners would eat with their bare hands. It was what saved Jeepney then, she quipped.

“We turned it around, and for those wondering about now, I say go for the boldness of the flavors. Dial it up instead of dial it down,” she added.

As she closed her talk, Ponseca mentioned about how Filipino food in the United States has evolved and that now, more than ever, the next generation of Filipino American chefs have access to what she referred to as the “4Cs”: capital, creativity, consciousness and community.

“Money is running out and if our doors should close, another door will open,” she said. “We have not come this far only to get this far.

Buy Filipino products

Five concurrent breakout sessions followed and they focused on topics that are key to the current environment. Breakout panelists include successful Filipino chefs, technology trailblazers, and industry experts.

The Philippine Department of Trade and Industry and the Department of Tourism made their presentations as well to help connect Filipino food producers and manufacturers with end-users across America.

Celynne Layug, trade attache of the DTI, talked about the journey of products and ingredients from the Philippines. Among the products she mentioned include coconut byproducts which have been used by private labels including Costco and Trader Joe’s and companies like Nestle.

Layug also talked about the platforms and specialty stores where Filipino products are now available and the companies which use Filipino ingredients such as ube and pili nuts in their products.

“We also have new and innovative products including the line of Mama Sita’s vinegars including cashew vinegar, bean to bar artisan chocolates, volcanic pili nuts from Bicol and the “dinosaur egg,” among others,” she added.

Dinosaur egg or asin tibuok is considered by enthusiasts as the rarest among Philippine sea salts from Bohol which is now imported to the United States. It is currently sold at $149.99 per “egg”.

“It is an age old craft but it is a dying process so we are hoping that the remaining family in Bohol which makes it is able to preserve this tradition,” Layug shared. Called dinosaur egg because of its shape, this salt is grated over a dish and takes up to four months to make.

Getting these products to the United States is already a feat, according to Layug, but surviving the competition is another battle that needs to be hurdled. She suggested patronizing Filipino products when we see them in our local groceries or supermarkets.

“Let us harness the power of the Filipino diaspora,” she said, adding that there is a strong need to advertise the availability of these products.

PJ Quesada, one of the founders of FFM, said he wanted to leave the participants with three points as he closed the summit’s proceedings.

“Rethink the stories you tell because your stories matter now more than ever; we have to be fluid and adaptable because there’s so much uncertainty right now and we have to survive this; and finally, experiment with new things, don’t be scared,” he said.

The online summit brought together some of the most prominent members of the Filipino food business community in the United States to discuss the economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic and develop actionable solutions that will keep the Filipino food industry competitive in a post-COVID marketplace.