A LOT of people have channeled their inner chefs and bakers as a way to cope with the global pandemic and after almost 12 weeks in lockdown, there is a need for more creative recipes. These home cooks, amateur chefs and bakers are ready to expand their repertoire and go beyond grilled lemon chicken and banana bread.

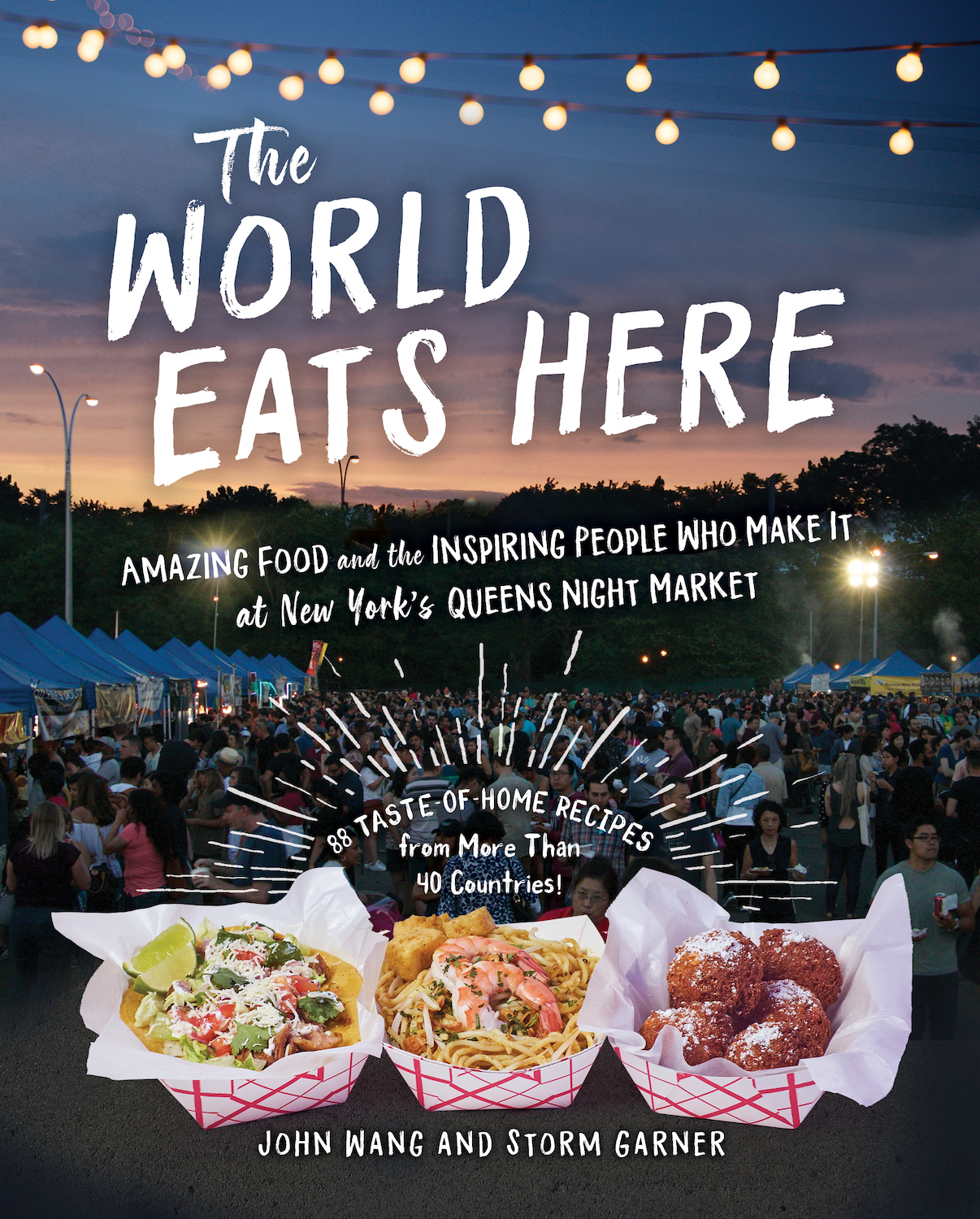

Enter “The World Eats Here,” a new cookbook from the people behind Queens Night Market. Now, home cooks can recreate the dishes they have eaten at QNM, whether it’s rellenos de papa from Puerto Rico, Cambodia’s fish amok or choripan from Argentina.

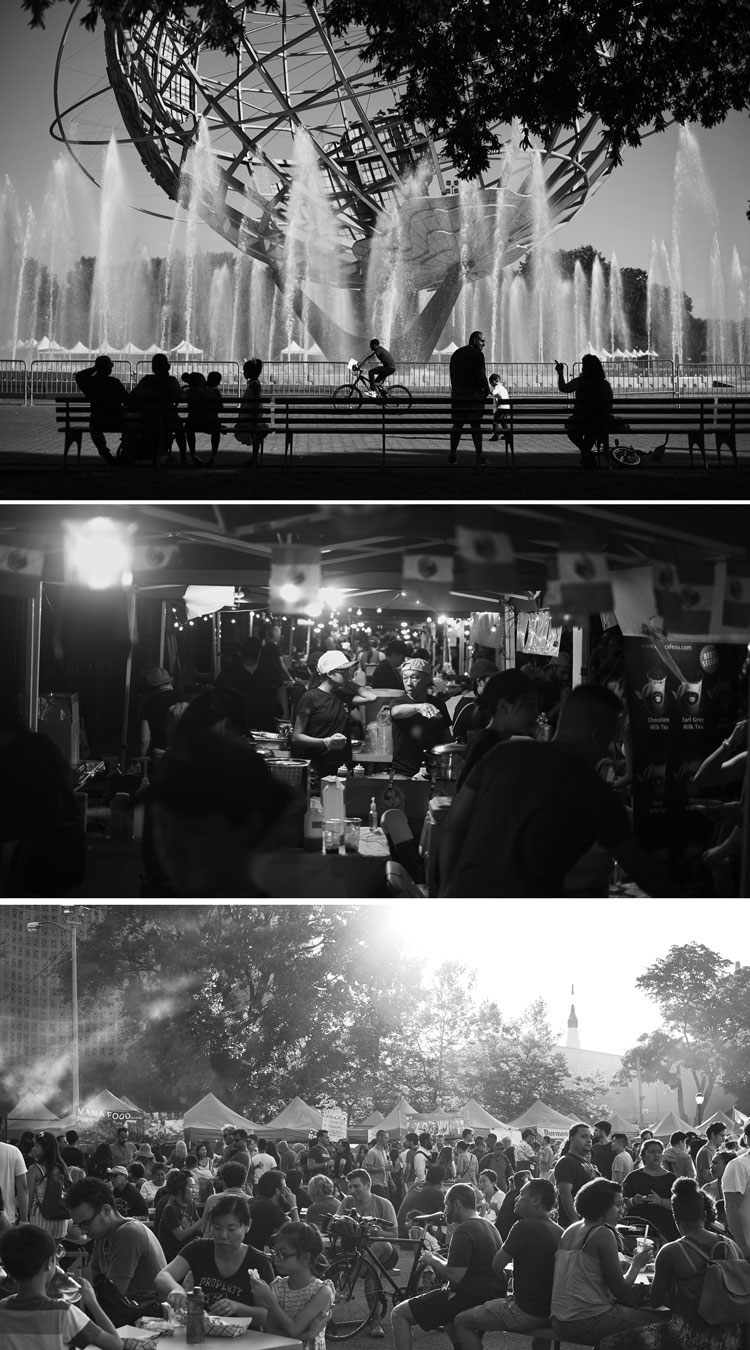

In less than five years, Queens Night Market transformed portions of Flushing Meadows Corona Park behind the New York Hall of Science into a family-friendly open-air night market and an affordable foodie destination, where adventurous palates can have crispy dinuguan one night and Salvadoran pupusas or cachapas from Venezuela the next.

The diversity of the vendors is of the roof that founder John Wang promises guests will almost always find something new every Saturday. On any given night, they have up to 60 food vendors and up to 30 nonfood vendors. It’s like travelling around the world in one night and devouring international flavors for as low as $5 per dish.

Since it launched in 2015, the Queens Night Market has attracted well over a million visitors and represented over 90 countries through its vendors and their food. Last year was the event’s busiest, averaging over 13,000 attendees each Saturday night from mid-April to October.

It’s not easy to get in though since they typically get about 700 vendor applications per year, all applications submitted online.

For Wang, who was inspired by the summer night markets he visited in Taiwan, the most important part of the application for food vendors is their response to the section asking applicants to relate the food they want to sell to their personal and cultural heritage.

“Our goal is to share traditional “ethnic” dishes, made by the people who grew up eating it,” he shared.

And since the market is in Queens where most of the Filipinos in New York live, there are three vendors that sell traditional Filipino dishes, including balut. Lapu Lapu Foods, Kanin NYC and Grilla in Manila hoist the Philippine flag every time they open their respective stalls.

Wang and his wife Storm Garner, a filmmaker and historian, had been toying with the idea of coming up with a cookbook that features the recipes of the mostly immigrant vendors that they work with. The project got off the ground back in 2018, when Marc Gerald, their literary agent approached them.

When Experiment Publishing accepted their book proposal in early 2019, it was off to the races. John and Storm started collecting their vendors’ recipes and their oral histories and in a little over a year, they have a book that celebrates the tasty recipes, the inspiring stories, and the diverse backgrounds of over 50 of their vendors. The budding entrepreneurs behind Lapu Lapu Foods, Kanin NYC and Grilla in Manila are part of the book and they are happy to share their respective immigrant story.

So far, advance recognition of the book includes being named as one of the “Top Ten Best Cookbooks of 2020” by Esquire and one of the six “ Best Cookbooks to Try in Quarantine” by Fortune. The book is an Amazon cookbook of the month, and was also recommended as a favorite by Foreword Reviews.

“We hope the book will inspire readers to venture outside their own culinary and cultural comfort zones,” Wang told the Asian Journal. “While the Queens Night Market is postponed until it’s safe to welcome back the hundreds of thousands of visitors we get each year, we hope The World Eats Here can keep us connected to their hearts, souls, and stomachs.”

The Queens Night Market was scheduled to open its sixth season last month, but has been indefinitely postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic. They are hoping for a late summer opening, keeping an eye on July, but will continue to follow guidance from the governmental and scientific authorities.

Beyond Fear Factor

Jay and Jerrick Jimenez run Grilla in Manila, which started in 2016 as a BBQ stall and they participated in various summer markets across the city.

“I read the customer reviews and was immediately impressed [with] what was said and decided to join. Our first day was a success, selling our famous Pork BBQ, Chicken BBQ and Shrimp BBQ kebabs,” Jay told the Asian Journal. “The environment was very different from all other events that we joined, it was more family-oriented.”

On their second year at QNM, they switched to Longganisa Burger, Crispy Dinuguan, Balut and Turon with Ube Ice Cream.

Balut and dinuguan are two of the Filipino dishes that have become infamous because of Fear Factor and Andrew Zimmern’s Bizarre Foods. Jay and Jerrick decided to use that to their advantage,

“These are two items on our menu that spark a lot of interest,” Jay said. “Our balut is served at 14 days old, which is a lot less scarier image than the 17-20 days old. It is less developed than the balut we have at home. We let our customers know that though it is a less developed egg, it does not lack in taste and the experience.”

And then come to question about what dinuguan is.

“We simply say, “Pork blood stew with crispy pork belly” served over rice. We also educate our customers that the classic dinuguan is served with pork innards and ours is slightly different because we use crispy pork belly,” he explained. “We believe that people will be extra iffy if we serve the classic version. This way, we provide the flavor in a less scary presentation. And on their first bite, they know what the buzz about dinuguan is all about and they keep coming back for more.”

Grilla in Manila will soon be branching out to the food truck scene and will also be releasing their own line of vinegar sauce that can also be used as marinade and it’s called Kuya Jay’s Spice Vinegar. Because of the global pandemic, the launch is delayed but they are hoping to launch by the end of the year.

Opportunity For A Do Over

Judymae Esguerra is the woman behind Kanin NYC. For the book, she shared her family’s lugaw and leche flan recipes.

Esguerra thought long and hard as to which Filipino food she can sell so she can get accepted as a QNM vendor.

Her ideas ranged from Filipino comfort food not sold by the other Filipino vendors, food that are uniquely Filipino but relatable to non-Filipinos and food that she has fond memories of growing up in the Philippines.

“Lugaw was the first one I came up with since it is comfort food and I can offer it as either arroz caldo (with chicken) or goto (with tripe). I felt it was a must to sell the shaved ice dessert/drinks since it’s summer and lumpia shanghai because of its popularity,” Esguerra said.

For Esguerra, setting up her own small business was her opportunity for a do over, since she realized she was unhappy despite the success she has achieved in her first 20 years in the United States pursuing what she thought were her goals and dreams.

“All along I was asking, ‘how do I reinvent myself?’ and it took me over a decade to answer this question and that was how Kanin NYC came about,” she said.

Her family loves going out to eat, discovering and trying new things, and they have known about Queens Night Market since its opening through social media but did not try it out because of the reported overcrowding.

In 2018, she went to the market with her family and friends and she fell in love.

“We were able to try so many different foods from different countries it was like traveling the world without breaking the bank. The atmosphere was casual and friendly I was having chats with strangers,” she said. “My belly was full and I was happy and felt at home that I checked out the QNM website on how to be a vendor that very night so I can be a part of it. I felt QNM will be my safe space for a do over.”

Now, as a vendor, she is faced with a conundrum: deciding how much food to bring and sell. Too much becomes a waste of money and too little is a waste of an opportunity to sell and a disappointment to customers when she puts up those “sold out” signs.

Selling the Classics

Alfredo and Marienits Pedrajas run Lapu Lapu Foods. For the cookbook, they shared their chicken adobo recipe, a mainstay at the restaurant they ran in the Philippines for 15 years before moving to New York.

Lapu- Lapu Foods started as a food processing company in February 2017. They sold adobong mani, hot and spicy and garlic flavor and they initially partnered with a company to distribute their product for the whole east coast. Things didn’t prosper so they decided to market it themselves instead.

They discovered QNM through an online search and they realized it was a good platform where they can test their products in the market. They found out adobong mani was not enough for the market, so they added the Filipino classics like chicken adobo, lumpia, and kwek-kwek, which became big hits at the market.

“As for our future plans, we had an idea on opening up a restobar, but because of the pandemic, we might have to re-think and analyze what would be best to do,” Pedrajas told the Asian Journal.

Bridging Cultures

Wang shared that most of the recipes in the book were being documented for the first time.

“Getting recipes that had never been written down before, and often never shared before, onto paper with standard measurements in an easy-to-follow format was a challenging and iterative process,” he said.

The dishes represent family traditions, cherished personal memories, tributes to parents or grandparents, special occasions, or cultural staples.

As for the vendors’ stories: Wang and Garner wanted them to help readers understand the chefs’ personal connection to the food they make–did they learn the recipe from a beloved grandmother, for example, or was it a special treat they would sneak out to get as a teenager in a homeland far away, that they learned to make themselves later in the US out of nostalgia?

“We wanted readers to get a sense not only of chefs’ food careers to date, but also of their voices, and personalities, and unique life journeys outside of the food world too, often including juggling multiple jobs and cultural identities,” Garner said.

In the book, each recipe is paired with a portrait and a personal narrative adapted from Garner’s oral history interview with the recipe’s creator, or sometimes the chef’s spouse or child who started the business to showcase a family member’s talent, painting a multidimensional collective portrait of small family-run food businesses in Queens today.

“We wanted readers to get a sense not only of chefs’ food careers to date, but also of their voices, and personalities, and unique life journeys outside of the food world too, often including juggling multiple jobs and cultural identities,” Wang said.