LAST month, the grassroots film distribution company ARRAY Now kickstarted its inaugural ARRAY 360, a special six-week program that celebrates the craft of filmmaking and highlights filmmakers and artists.

Founded in 2010 by famed filmmaker and advocate Ava Duvernay (“Selma,” “A Wrinkle in Time”), ARRAY has a special mission to amplify emerging filmmakers of color by celebrating diversity and representation.

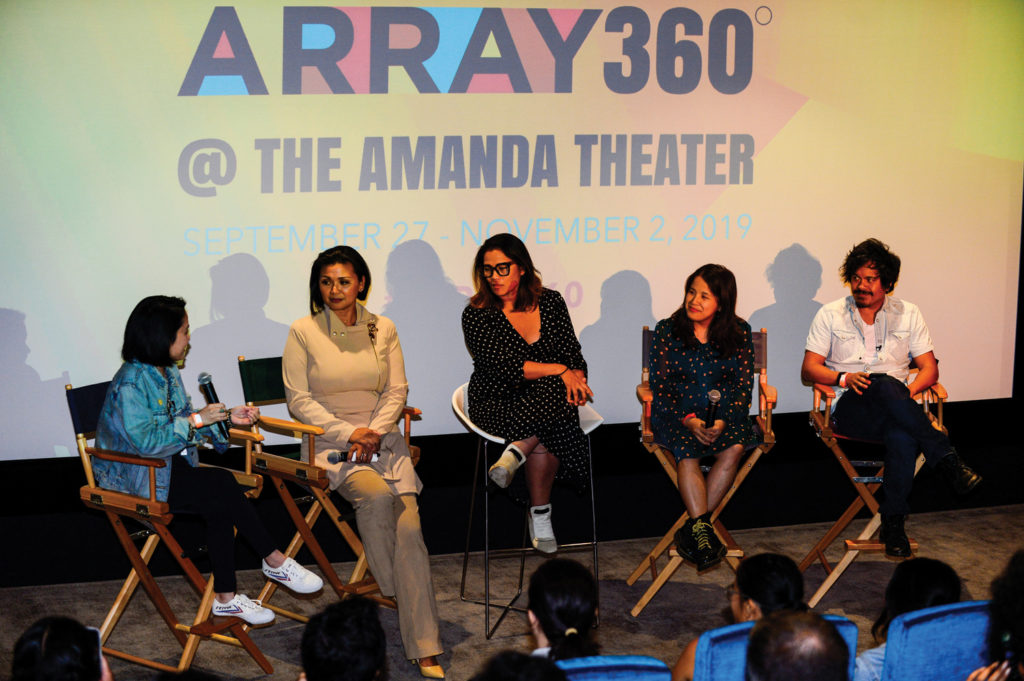

Living up to that objective and just in time to celebrate Filipino American History Month, ARRAY Now on Saturday, October 5 hosted its second weekend of ARRAY 360 with the Filipinx Film Program, a day-long honor to the history, present and future of Filipino filmmaking.

Situated in a colorful millennial-friendly complex in Los Angeles’ Historic Filipinotown, the ARRAY Now campus feels like a microcosmic collective of the city’s creative community, a progression towards widening inclusivity for filmmakers of all backgrounds.

In addition to screening the 1976 drama “Minsa’y Isang Gamu-Gamo (Once a Moth)” by Lupita Aquino-Kashiwahara and the 1980 romcom “Kakabakaba Ka Ba (Does Your Heart Beat Faster?)” by Mike De Leon, ARRAY 360 screened two widely anticipated films by two Filipino American filmmakers: “Call Her Ganda” from PJ Raval and “Yellow Rose” from Diane Paragas.

The latter two films have been abuzz within the independent film scene, both praised for their spellbinding storytelling and timely social messages.

“Call Her Ganda,” the documentary about Jennifer Laude, the transgender Filipina who was allegedly murdered by a U.S. serviceman in 2014, highlights contemporary efforts for justice set against the backdrop of the residual effects of American colonialism.

As previously reported in the Asian Journal, “Yellow Rose,” the musical drama and 2019 festival darling that has been racking up jury awards across the country, tells the story of an undocumented 17-year-old Filipina named Rose who finds herself embarking on a winding journey of self-discovery.

Though both films tackle very contemporary current events, the sociopolitical elements are nothing more than circumstantial to the central theses of the human perspective and the power of community.

For “Call Her Ganda,” Raval followed the Laude family and their attorneys throughout the subsequent trials against Laude’s alleged murderer, a delicate process that provided Raval a unique learning experience. Born in Clovis, California and, like many second-generation Filipino Americans, Raval didn’t grow up with a full understanding of Filipino culture and its history.

Initially, Raval didn’t feel like he had “the right” to tell the story of Laude and the subsequent legal and emotional battles the Laude family faced, suggesting that a trans activist in the Philippines would be better suited.

But when Virginia “Virgie” Suarez, one of the Laude family attorneys, encouraged Raval he was the right person for the job, he accepted as long as he had the permission and blessing of the Laude family, which he received.

“It kind of became clear to me that maybe I am the right person to make this film because ultimately I’m the person who needs to see this film,” Raval told the Asian Journal. “I grew up in the United States so I know, first-hand, how little information there is about the Philippines even though I know how much of a history the United States has had in terms of shaping the history of the Philippines and the modern-day structure of the Philippines.”

He added, “I felt like as a Filipino American I had a foot in both places, I saw this as my opportunity to contribute to the Justice for Jennifer movement that was happening.”

Released in 2018, “Call Her Ganda” made the festival rounds, garnering multiple awards including the Grand Jury Award at the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival in 2018 and the Jury Award for Best Documentary Film at the Tampa Bay International Gay & Lesbian Film Festival.

“Call Her Ganda” deals with tragedy set against the clashes between anti-trans sentiment and trans activism as well as U.S. military presence in the Philippines and the fight for total Philippine sovereignty. But that’s not the heart of the film, Raval shared.

“At the end of the day, a mother lost her child. That’s really all it is, and nobody has the right to take someone’s life,” Raval said of his intention of making the documentary. “Certainly, a story like this, we can talk about from the perspective of colonialization, imperialism, and trans rights and geopolitics but at the end of the day, it’s about a mother who lost her child and that, if anything, connects all of us whether you’re trans, Filipino, American or whatever, everyone should understand that concept of loss and accountability This is really a universal experience even though it’s been talked about in a very specific way.”

The same could be said for Paragas’ “Yellow Rose,” which stars the Tony-nominated Eva Noblezada as Rose, a scrappy and determined aspiring country music star who finds herself in a precarious position once her mother Priscilla (played by Princess Punzalan) gets deported.

Rather than making an overtly political film with a social justice agenda, Paragas set out to tell a coming-of-age story that reflects her upbringing as a Philippine-born, Texas-raised Filipina.

As a child, Paragas and her family fled the Philippines during the martial law era and settled in Lubbock, Texas. “Yellow Rose” can be seen as a cinematic roman à clef, with Rose’s perspective largely built from experiences from Paragas’ formative years in Texas.

“I think movies that are about the South and deal with racism — which this film does — always get the low-hanging fruit of the overtly racist redneck. I actually didn’t want to do that because my intention was to show what I think is great about America which is our ability to have empathy, compassion and help people who are in need,” Paragas shared.

“In many ways, this film is my love letter to Texas,” she added.

That being said, Paragas also noted that she wanted to create a film that was distinctly American told from the perspective of a Filipina. Stylistically, the film draws inspiration from the sensory nature of Terrence Malick’s and Wong Kar-Wai’s films. It also captures the warmth and the tenuousness of the western genre, as seen in the filmography of John Ford.

“I wanted to make an iconic film that anyone could relate to, I wanted to make a movie for the lolas as much as for the young people and as much as film nerds,” Paragas shared.

Citing the Harlan Howard quote that says, “Country music is three chords and the truth,” Paragas noted that “I kind of wanted to do a country song as a film, something that is something authentic, simple and straight with a lot of emotion. That’s what I was going for in terms of the tone of the film: a simple, true authentic story that feels real and grounded in something poetic.”

Deservingly, “Yellow Rose” has caught the attention of film festivals for capturing a timely story of being undocumented and redefining what it means to be an American.

But more than that, the film sets an example for the future of Filipino American cinema as a rich artistic reservoir, a gold mine with important, prescient stories that have yet to be excavated.

“It’s a great time to be a filmmaker, as a Filipino American because although we’re living in a time where our differences are being highlighted, there’s also this contrasting wave, this idea that people and studios are now grasping that Asian films have a place in the market. And my hope is that that continues and we get to see more films from our community,” Paragas shared.