For years, the United Nations awards people from around the globe with the title “champion of the earth.” The said title is considered the institution’s highest environmental honor as it recognizes people both from the public and private sector who played a significant role in promoting ways to help the environment. This time, one Filipina gained the spotlight as she shared the struggles she encountered in defending the environment in her mother country, the Philippines.

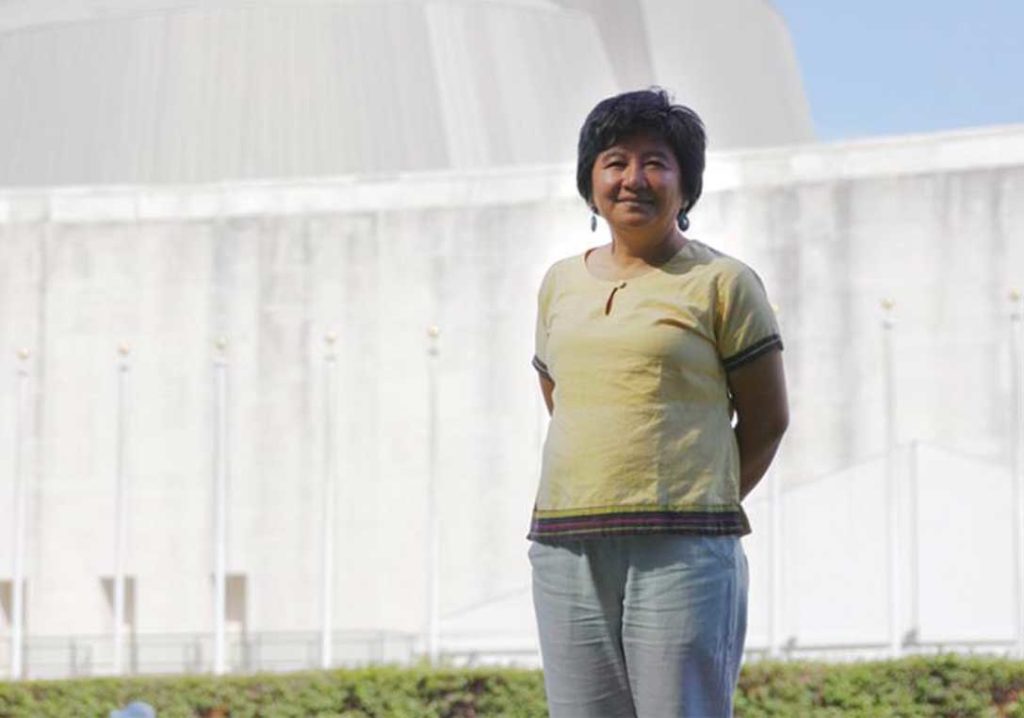

As an indigenous rights activist and environmental defender, Joan Carling never had it easy. For more than two decades, she has been defending land rights from grassroots to international levels. However, despite the obvious concern she has been dedicating to a just cause. She still earns the ire of government officials to the point where she was somehow labeled as a terrorist.

“I have dedicated my life to teaching about human rights. I have spent much of it campaigning for environmental protection and sustainable development. So, I was surprised to learn that I was labeled as a terrorist,” Carling recalled.

Since her work revolved around the protection of land rights of indigenous peoples, ensuring sustainable development of natural resources and upholding human rights of marginalized people, she most certainly fought against the norm and status quo. She did not let those in power trample the rights of those in the vulnerable communities. Threats against her life and security did not stop her from fighting with and for the people.

“In February this year, I was placed on a list of alleged armed rebels in the Philippines. I haven’t been home since. It has uprooted me: I fear for the safety of my family and friends. But I need to stay more motivated than ever. I cannot give up the fight for my people,” the environmental activist added.

As a global advocate in UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and REDD+, one would expect that she would be treated high up the pedestal. Not only did she served as the Secretary General of the Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP) twice, she also became a local Chairperson of the Cordillera People’s Alliance in the Philippines. A feat not many would dare to achieve, let alone take on as a responsibility.

“I am from the Kankanaey tribe of the northern region of Cordillera: the land of gold. Our land sits on a mineral belt, rich in gold, copper and manganese. It belongs to us, the indigenous peoples of the Cordillera. Yet, our natural resources and way of life are threatened by mining companies and other so-called “development projects,”

Her love for her homeland perhaps became her motivation to continue the cause. She could have broadened her horizons as she was appointed by the UN Economic and Social Council as an indigenous expert and also served as a member of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. However, her love for the place she grew up in remained. Her memories of the place pushed her to become the defender she is now.

“I spent my childhood in a remote forest under logging concession. Nomadic communities from the forest often visited, traveling up to six hours to exchange their sweet potato or other crops for rice or sugar, which they couldn’t grow themselves. My parents would offer a meal, and it was from these simple exchanges that I learned humility, reciprocity, and respect for our diverse indigenous communities and cultures,” Carling narrated.

“I was struck by their sense of community; their simple lifestyles, their cooperation and selflessness. Their culture and values are intrinsically linked to the land, their livelihood and identity just like my own kankanaey people. The way these people care for each other and the environment deeply moved and inspired me,” she added.

As a member and co-convenor of the Indigenous Peoples Major Group for the Sustainable Development Goals, she became exposed to the communities in the Philippines, Asia and different parts of the world. She noted the militarization indigenous people were experiencing and so it strengthened her fight to promote human rights and environmental sustainability.

“I’ve seen indigenous peoples living in remote villages silenced, unable to raise their voice to protect their land and the environment. I have worked with them for more than a decade to raise awareness, through protests and dialogue. We engaged with mining companies, dam builders, local authorities and the media, and formed support groups alliances for the protection of human rights and the environment. Despite the threats, risks, and more repression, I persevered in my work, along with other dedicated leaders,” Carling explained.

Carling used the spotlight not to show the things she had achieved but to shed light on the issues with the least attention given. She urges the leaders globally to campaign for human rights and sustainable resource management, community-based climate change adaptation and renewable energy.

“Indigenous peoples are not the enemies. We are not against development. We are conserving our environment for the future of humanity. But we cannot do this alone. The global community, governments, companies and civil society must act in solidarity, and assume responsibility for realizing sustainable development for all,” Carling urged.

Carling may be the champion of the earth but we are all its inhabitants. Whatever happens to this living sphere will be experienced by everyone no matter how well-off one can get. To be apathetic is a choice, but it does not sound like a good one if you think about it. (With reports from United Nations Environment Programme)