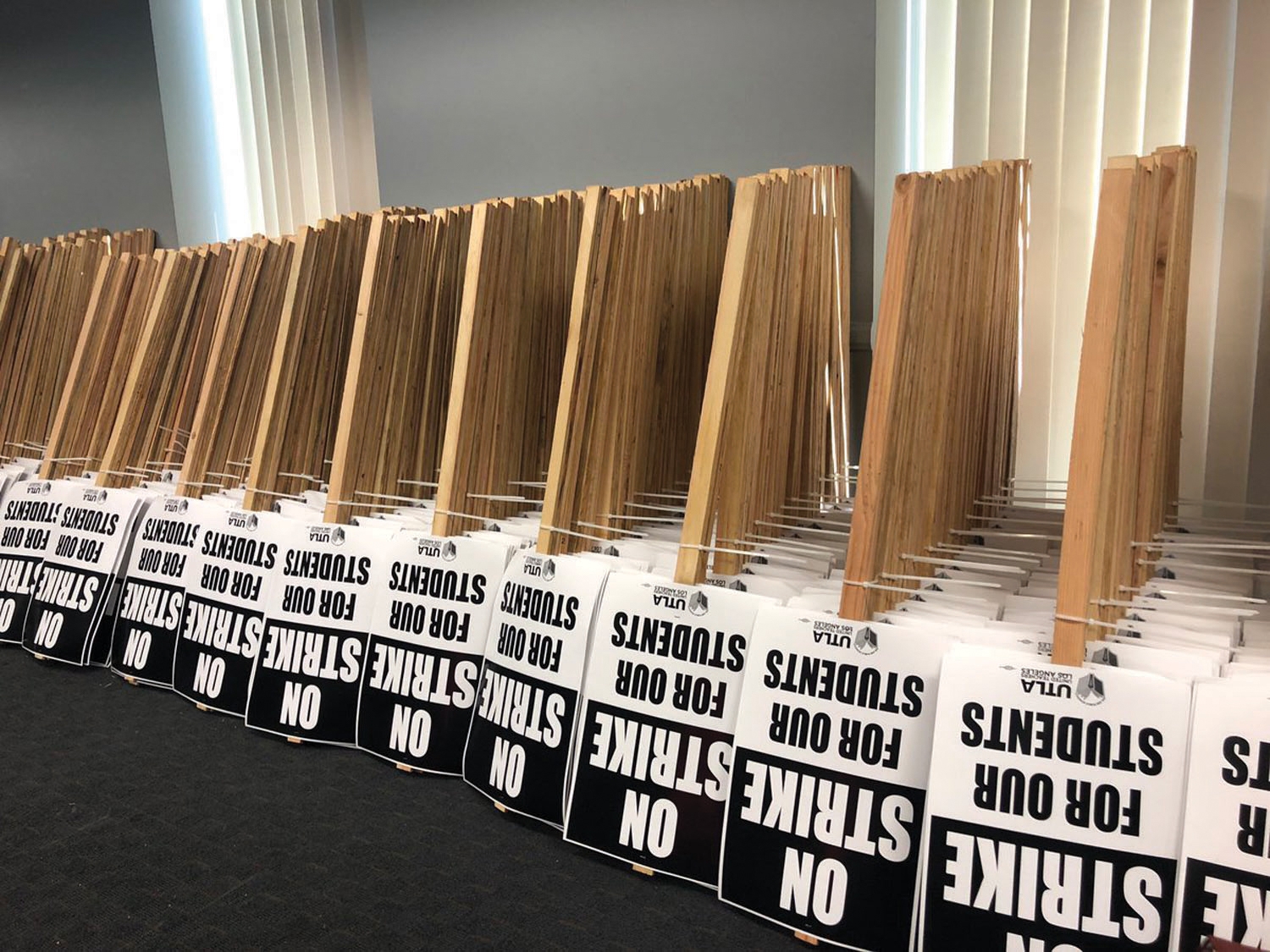

Following rejected LAUSD proposal, teachers union prepares to strike on Jan. 14 as educators fight for smaller classes, more resources

After a nearly two-year-long fray with the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), thousands of educators, students and parents are preparing to strike on Monday, Jan. 14.

The United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA) has been calling on the LAUSD — the second largest public school district in the country — to address increasing class size and staffing issues among other concerns.

After a cumbersome bargaining period between the union and LAUSD which yielded no solutions thus far, the union plans to hold the Monday strike following a superior court ruling on Wednesday, Jan. 9 that the union may legally strike.

Previously scheduled for Jan. 10, UTLA President Alex Caputo-Pearl announced that the strike will start on Monday, Jan. 14 over uncertainties concerning the district’s injunction that the union had no legal right to strike.

The strike was originally going to be held on Jan. 10 as the union announced weeks ago. But the LAUSD said that UTLA didn’t submit the required formal notice of the strike to the district. The union believed it was easier just to delay the strike a few days pending the judge’s ruling.

“Unlike [LAUSD Superintendent Austin] Beutner and his administration, we do not want to bring confusion and chaos into an already fluid situation,” Caputo-Pearl wrote in a statement released on Wednesday, Jan. 9. “Although we believe we would ultimately prevail in court, for our members, our students, parents and the community, absent an agreement we will plan to strike on Monday.”

The union has been in the bargaining period since Spring 2017 but no resolutions have been agreed upon. This will likely result in a sizable demonstration on Monday that highlights, not only the district’s problems, but also those of the U.S. public education system at large.

Why are teachers striking?

The two main issues at the center of this strike are class size, and increased staffing to shrink the growing classrooms.

And those concerns exemplify the state’s overall classroom size problem. According to data on UTLA’s website, California ranks 48 out of 50 in class size, meaning that LAUSD teachers have among the largest class sizes in the state and country.

After two years of bargaining, mediation and fact-finding periods, the union remains unsatisfied with every offer the LAUSD has brought to the table, said Jollene Levid, a regional union organizer with UTLA and former school social worker, who said that

UTLA is fighting for a “progressive, student-centered contract and for, frankly, better learning environments for students and a better working environment for educators.”

Media were quick to characterize this as a salary dispute, as many teachers’ strikes across the country had been centered around teachers’ wages.

But that’s hardly the primary mission, said Levid, who is also a former LAUSD student. Levid described the prime goals are to decrease the size of the average classroom and to increase staffing across the district.

“The No. 1 issue at the table is class size, by far,” Levid — who is Filipina-American — told the Asian Journal in a phone interview on Thursday, Jan. 3. “A lot of media outlets have really made this about salary, but we’ve already been offered a 6 percent salary increase.

That was already on the table [and] we could’ve taken that and walked away, but that’s not the main issue at hand. It’s only a part of the picture.”

The other main issue is proper staffing.

“I remember being a student and having a nurse every day. We don’t have that right now,” Levid said. “We also need more social workers who can address the emotional needs of our students.”

Dahlia Heights Elementary School in Eagle Rock, for example, only has a nurse who comes in on Wednesdays. Some schools do not have a regular social worker or librarian, other staff members who help run the school.

Why is this important?

To understand the scope of the teachers’ cause, one must understand the scope of the district itself.

There are roughly 694,000 students in the vast K-12 district alone in Los Angeles, the same amount of public school students in the entire state of Oklahoma. The district oversees more than 900 schools and 187 public charter schools in a region diverse in socioeconomic levels, race and ethnicity and familial history in education.

In a statement provided to the Asian Journal, the LAUSD said that it welcomes “UTLA’s willingness to return to contract negotiations to avoid a strike that would do nothing to increase funding for public education or would only hurt the students, families and communities most in need. Los Angeles Unified remains committed to doing everything possible to avoid a strike and provide Los Angeles students with the best education possible.”

Most recently, on Monday, Jan. 7, the LAUSD offered its first proposal to the table in months that would essentially “reset” the contract mandate on class size, which is among the most crucial issues being brought to the table.

Though the control is not in the hands of the LAUSD alone. The State of California currently allocates $16,000 per pupil to the LAUSD per year.

On Wednesday, Jan. 9, Beutner was in Sacramento where he met with state lawmakers concerning more resources and funding for the district. In an interview with KCRW, Beutner said he supports the hiring of more teachers, nurses, counselors and librarians as well as the 6 percent teacher salary increase.

“We’ve put a very full offer on the table. We’ve been told by the state, the county, the independent fact finder…that we’re spending money too fast [and] we will run out very soon,” Beutner said, urging UTLA to “come back to the table” for further advise.

But the union claims that the district has a reserve fund of $2 billion that could fund the very issues that Beutner says he supports.

According to Levid, this mandate allows the district to increase class size in the event of a “fiscal emergency,” events which Levid said are, essentially, arbitrary.

“They don’t have to prove that they’re in a fiscal emergency, so they triggered [a fiscal emergency in Oct. 2018], but we know — and the fact-finding panel and the mediators — everyone who has looked into the LAUSD budget has confirmed that LAUSD has a $1.86 billion reserve,” Levid asserted. (Efforts to reach out to the LAUSD on confirmation of this claim have been met with silence.)

The bigger picture

As racial divisions and ethnic identity become contentious topics across the country, the teachers’ strikes — and the fight for quality public education — highlights the overall injustice against communities of color.

A 2018 report from the Pew Research Center, students of color (non-white students) make up more than half of the 50 million students enrolled in public schools. It’s a relatively unsurprising figure that reflects migration patterns over the last three decades, particularly from Latin America and Asia.

In the LAUSD, Latinos comprise 73.4 percent of the student body (as of the 2018-2019 school year). While Asians comprise 4.2 percent, Filipino students make up half of LAUSD’s entire Asian student body (2.1 percent).

Why is race important? A 2016 Stanford study of students in the largest 100 U.S. cities found that students of color are more likely to attend public schools where a majority of the students qualify as “poor or low-income.”

Referencing this study Janie Boschma and Ronald Brownstein of The Atlantic wrote, “The overwhelming isolation of students of color in schools with mostly low-income classmates threatens to undermine efforts both to improve educational outcomes and to provide a pipeline of skilled workers for the economy when such students comprise a majority of the nation’s public school enrollment.”

In short, increasing class sizes, insufficient staffing and low teachers wages are more likely to happen in public schools which minority students are more likely to attend.

The Filipino-American parents of a 4th grader at Mayberry Elementary, who asked to remain anonymous, expressed concern over the foreseeable “dwindling” of the American public school system.

The father, who is a professor of sociology at a community college, felt that there has been a “vague, yet definite grinding halt” in the fight to improve and expand resources for public education.

“Even if I wasn’t a professor, it wouldn’t be difficult for me to see the value we should all have for educators,” the father told the Asian Journal in a phone interview. “America is supposed to be the land of opportunity, right? And in that promise, the right to a good education. People move entire families so that kids get an education here. Yet, this is how we treat our teachers, and when you think about it, our students?”

Both parents felt that the swelling of class size is a concern across the country that should be prioritized by the federal, state and local government. Both parents are first-generation Filipino-Americans who had moved to the United States as children; they both were educated in the LAUSD.

Each remembered the importance teachers played in their upbringing and wish the same for their 10-year-old. They worry that if class sizes increase, the quality of education will decline to the point where they would consider sending the child to a private school.

But, of course, avoiding the high cost of private school tuition would be ideal and, as the mother said, “you shouldn’t have to pay for a school” that provides counselors, nurses and social workers on staff every school day.

“I worry because what if my daughter needs immediately to see a counselor or the school nurse and there isn’t one? Or what if the overall learning experience becomes troublesome with [the] current ratio of students to teachers? I think it already has become troublesome, and I think it’s a problem with an existing solution,” the mother said.