By Harold Clavite/Contributor

AT the end of a long work shift, Filipino nurse Jiggz Tabuclin would make it home in time to put his daughter to bed.

But amid the coronavirus outbreak, this is no longer the case. Tabuclin instead parks his minivan outside of the house, then prepares a makeshift bed out of a sleeping bag and a comforter.

The nurse, who works in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a hospital in Queens, New York, is one of the hundreds of health care workers left with no choice but to work extra hours, self-isolate and not be able to see their families as the pandemic worsens.

The decision to isolate from his own family came when COVID-19 cases started to grow exponentially in New York, where 1,550 people have already died by the end of March.

While Tabuclin would prefer to come home to his wife, a public school teacher, and their young daughter who has disability, he cannot take the risk of bringing the virus and infecting his own family.

“I am tired. But more than that, I’m always anxious while at work. At the end of each day, you wonder if you’re infected or not,” he said.

Only a few weeks ago, he was counting the days and looking forward to much-needed breaks and vacation time. Personal days off are no longer allowed and holidays are postponed indefinitely. Mandatory extra hours have become the new norm at work.

In Tabuclin’s unit, one nurse reportedly handles three COVID-19 cases in addition to regular patients. But this number could change anytime soon as patients pour in each day. Nurses are burdened with juggling between infectious disease patients and others who require immediate and thorough medical attention.

At the current rate, makeshift isolation units have been prepared. Within the ICU, the hospital crew has set up temporary barriers to isolate non-COVID-19 patients from positive ones. Tabuclin notes that it is not totally safe but somehow helps in the meantime.

Due to the volume of patients needing ventilators and intensive support, he worries that the whole telemetry unit might be converted into an ICU, but not all workers are trained in intensive care.

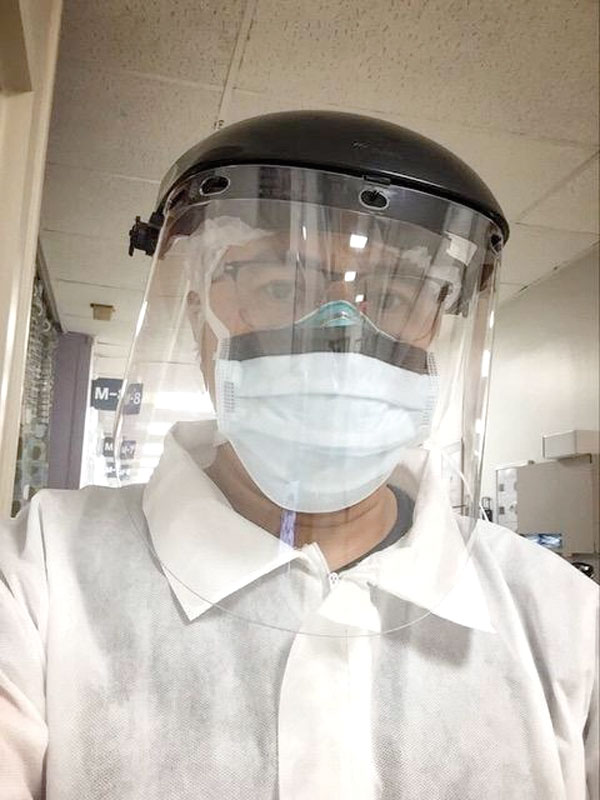

Personal protective equipment (PPE) has become scarce, causing health care workers to resort to improvising. Tabuclin and his colleagues had to buy their own gear while seeing others using garbage bags and other plastic materials to cover themselves. At one point, he had to use swimming goggles while handling patients as face shields were running out from stores.

Medical front-liners are at the fore of this warfare and are risking their own lives. With the increasing number of patients coming in each day, some of the nurses have become sick themselves. So far, one nurse has been diagnosed with the disease in Tabuclin’s unit.

But this is the sacrifice and commitment Tabuclin — who was a food attendant at a Filipino restaurant while he took his nursing degree — made when he became a nurse three years ago.

“My only wish now is for a cure against this disease to come out soon and maybe an assurance from authorities that they know what they’re doing to end this crisis so we can all go back to our families,” said Tabuclin.