By Vina Orden

IN early 2020, eight intergenerational, emerging and mid-career Filipino American artists from New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—Julio Jose Austria, Jeho Bitancor, Mic Boekelmann, Francis Estrada, Ben Iluzada, Ged Merino, Eva Marie Solangon, and Maria Stabio—formed the collective NExSE (for Northeast U.S. by Southeast Asia).

“I had felt isolated in Princeton,” Mic Boekelmann recalled in a recent phone interview. “So, I set a goal to connect with other Fil-Am artists on the Northeast Coast.” She consulted the Filipino American Artist Directory (created by Janna Añonuevo Langholz to bring together and uplift US- and Philippines-based visual artists) and was surprised to find others similarly disconnected from an artistic community in the US. After two exploratory meetings, the group of eight cohered as NExSE.

They initially were drawn to each other by their shared heritage and struggles as immigrants or children of immigrants, but more compelling exchanges ensued from their varied experiences as Filipino Americans and how or to what degree that was expressed in their art. This dynamic was ever-present as they navigated relationship-building and collaboration amidst a global pandemic.

NExSE’s Spoliarium Project, for example, was an experiment designed to introduce the artists to each other and test out virtual collaborations. Selecting the iconic painting Spoliarium by Juan Luna (arguably the first internationally recognized Filipino artist) as a reference point is significant, situating NExSE within a lineage of Filipino diasporic art that at once is influenced by and upends colonial traditions.

Philadelphia-based printmaker and book artist Ben Iluzada created a monotype ghost print inspired by Luna’s Spoliarium, passed it to Boekelmann who modified it with die cuts and woven paper made of abaca (or Manila hemp, grown in Bicol, Philippines where Boekelmann’s mother is from), who then turned it over to the next artist who transformed it further, and so on. In the resulting palimpsest, Luna’s ghost remains an invisible presence, even as each layer of erasures and additions creates new meanings and contexts.

The metaphor extends to contemporary Filipino and Filipino diasporic identities and cultures, which are simultaneous negotiations of the precolonial, colonial, and postcolonial. These tensions undergird work created this past year by NExSE, which will be featured in an upcoming exhibition at the Lewis Center for the Arts at Princeton University on October 6 for Filipino American History Month. Its title, 300 Years in a Convent, 50 in Hollywood, alludes to how many Filipinos understand their history in terms of Spanish and American colonization.

The “Philippines” and the “Filipino” have always been unstable constructs—designations foisted on an archipelago of 7,107 distinct islands and societies to signify possession by Spain under 16th-century monarch Philip II. Only in the 19th century did the Illustrados—educated natives like Luna and the writer José Rizal who had been inspired by the French Revolution—adopt the term “Filipino,” seeding the idea of a national identity that catalyzed the Philippine Revolution against Spain in 1896. Yet, as Luis H. Francia notes in A History of the Philippines, it was an identity “that reflect[ed] an improvisatory sense… blending then as now the indigenous and the foreign, the alien and the familiar, in a word, ‘Filipinizing’ them.”

A number of works in the show use language to explore the hybridization endemic to Filipino identity and culture. One of Ged Merino’s pieces, reminiscent of Duchamp’s “readymades,” is a gold filigree halo of stars (ubiquitous in depictions of the Virgin Mary) inscribed with a colloquial expression for surprise or disbelief, “SUSMARYOSEP,” also shorthand for the Biblical “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph.” Another of his pieces, a leather drape stenciled with dialogue excerpted from Jessica Hagedorn’s novel, Dogeaters—“Hoy, bruja! Kamusta? Ano ba—long time no hear!”—shows the easy commingling of Tagalog (one of 170 languages and dialects spoken in the Philippines), Spanish, and English in everyday speech.

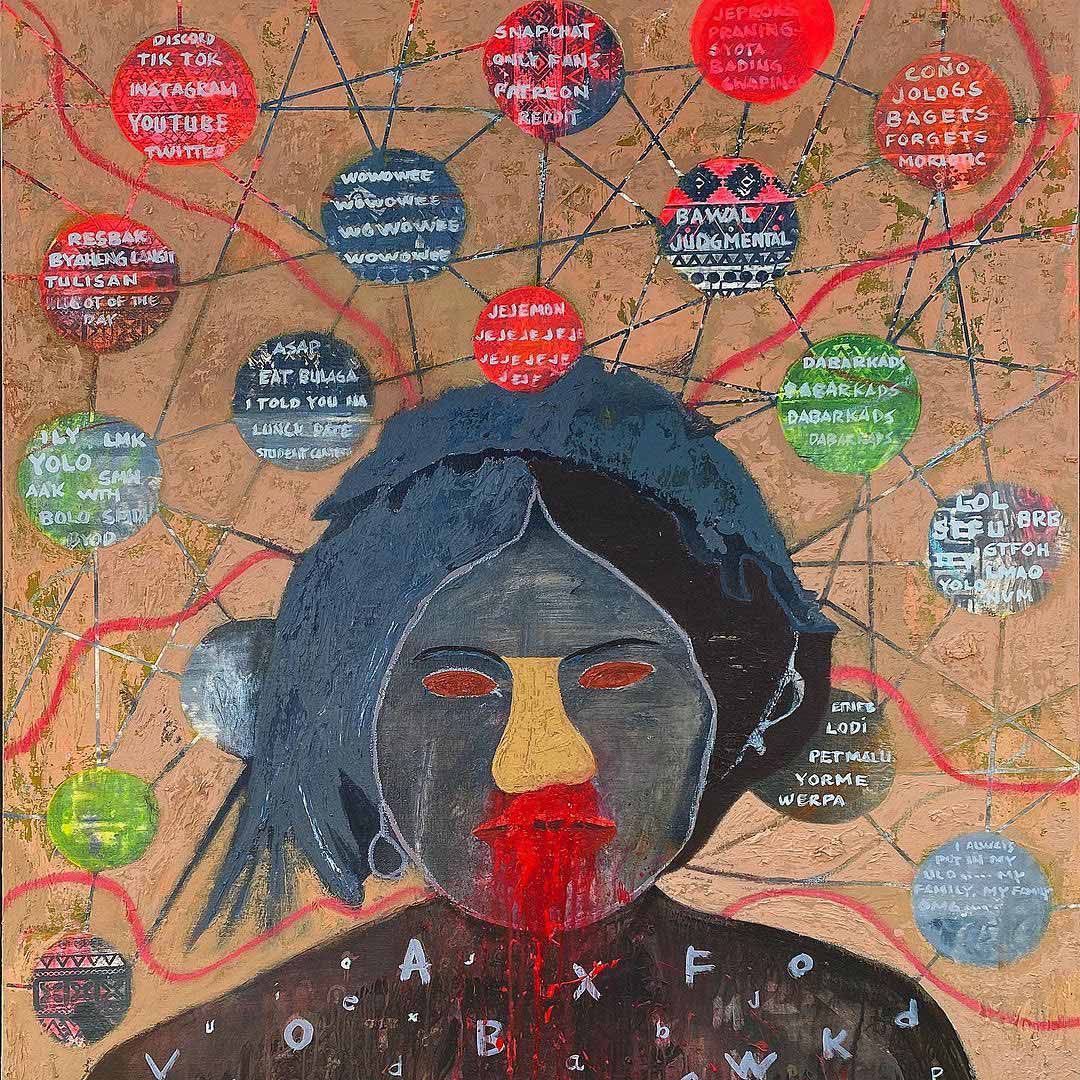

In contrast, Julio Jose Austria, who immigrated to New York in 2011 on an “alien of extraordinary ability” visa, illustrates the mental toll of code-switching. The background of his painting, Nosebleed, resembles a neural circuit, converging and diverging from groupings of words, acronyms, and colloquialisms in Tagalog and English, such as “BAWAL [forbidden] | JUDGMENTAL” and “I ALWAYS PUT IN MY ULO [head] … MY FAMILY, MY FAMILY | OMG …” In the center is a dark figure who represents a first-generation immigrant, blood gushing down their nose and mouth. Among Filipinos, “nosebleed” also happens to be a figure of speech for laboring to speak English with an American accent.

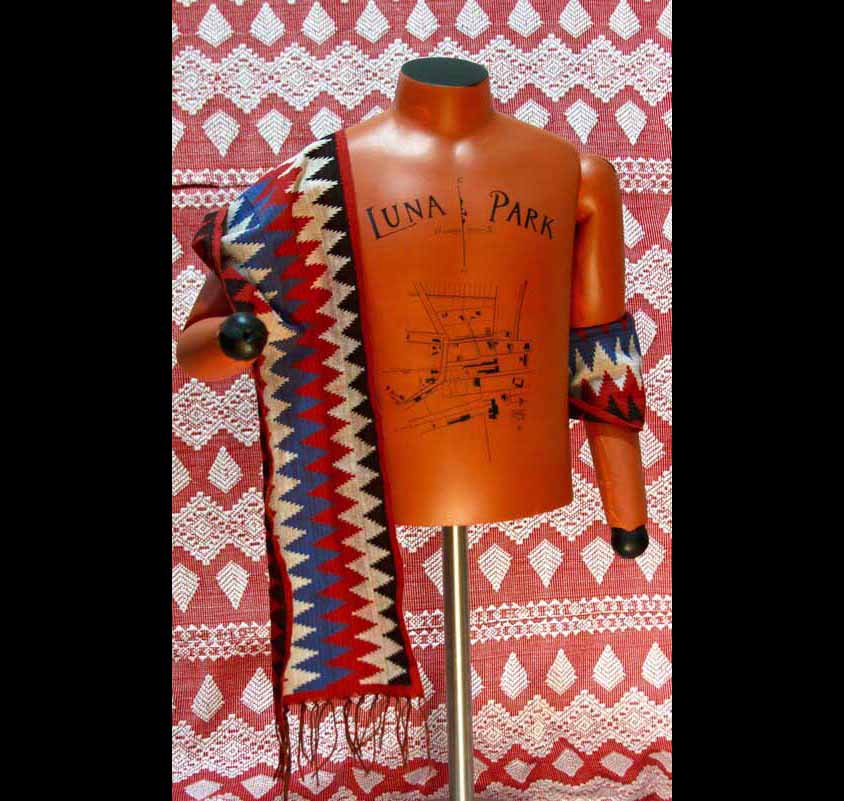

The identity, “Filipino American,” is also interrogated in different ways. Francis Estrada’s mixed media work, Escaping Dreamland, starts with a historical reference to make sense of “the complex relationship between the Philippines and the US—and our place in it.” A reddish-brown mannequin branded with a map of Luna Park recalls human zoos in the US and Europe at the turn of the 19th century, where Black and brown people (including the indigenous Bontoc people uprooted from the Cordillera highlands in the Philippines) were displayed in tableaux for white audiences’ entertainment. Foregrounding the mannequin are models of balangay, precolonial maritime vessels used throughout and beyond the archipelago—envisioning alternate, emancipatory possibilities for the Bontoc.

As a first-generation Filipino American, Maria Stabio’s connection with her heritage is tied more to memories than “identity in a national sense.” The paintings from her Eye of the Needle and Center Eye Study series layer familiar objects—tropical plants encountered on trips to the Philippines; a needle and winding thread that remind her of cousin who is a seamstress there; primary colors, which figure in the Philippine flag—in unfamiliar contexts, so they “begin to become something new.”

Other featured works include Jeho Bitancor’s audio interviews with three generations of Filipino Americans, embodied in the space by their personal effects; Boekelmann’s She’s Here, a terno dress the artist fashioned out of Manila envelope cutouts of sampaguita and gumamela flowers, along with words of affirmation in Tagalog and Bikolano, as “armor” for her daughter; and Eva Marie Solangon’s Allow Ilaw (light) and Remanifest Destiny—fluorescent, three-dimensional, conceptual self-portraits of the artist’s journey back from a fibromyalgia diagnosis and depression toward “self-rediscovery,” healing, and autonomy.

In 300 Years in a Convent, 50 in Hollywood, NExSE surfaces forgotten histories and resists, engages with, and transforms the detritus of Spanish and American colonization. It would be hasty to declare that the art has moved beyond postcolonialism—after all, the historical effects of colonialism continue to manifest in labor migrations from the Philippines, as Austria and Bitancor attest, and widening inequities in the pandemic also are exposing the limits of a hyper-globalist outlook. But outlines of the future emerge in liminal spaces, where artists like Stabio and Solangon move from a subjectivity grounded in memories and experiences outward, engaging viewers in the creation of new language, contexts, and possibilities for what curator Patrick D. Flores anticipates as a “third moment” in Filipino American art.

300 Years in a Convent, 50 in Hollywood opens at the Lewis Center for the Arts at Princeton University on October 6 from 10 a.m. to 8:30 p.m., with a walk-through at 4:30 p.m. followed by a panel (also livestreamed) with NExSE and Patrick Flores, professor of art studies at the University of the Philippines and Curator of the Vargas Museum in Manila, as well as Artistic Director of the Singapore Biennale 2019, moderated by Paul Nadal, assistant professor of English and American studies at Princeton, and Anne Cheng, professor of English at Princeton.