by Lauren Weber

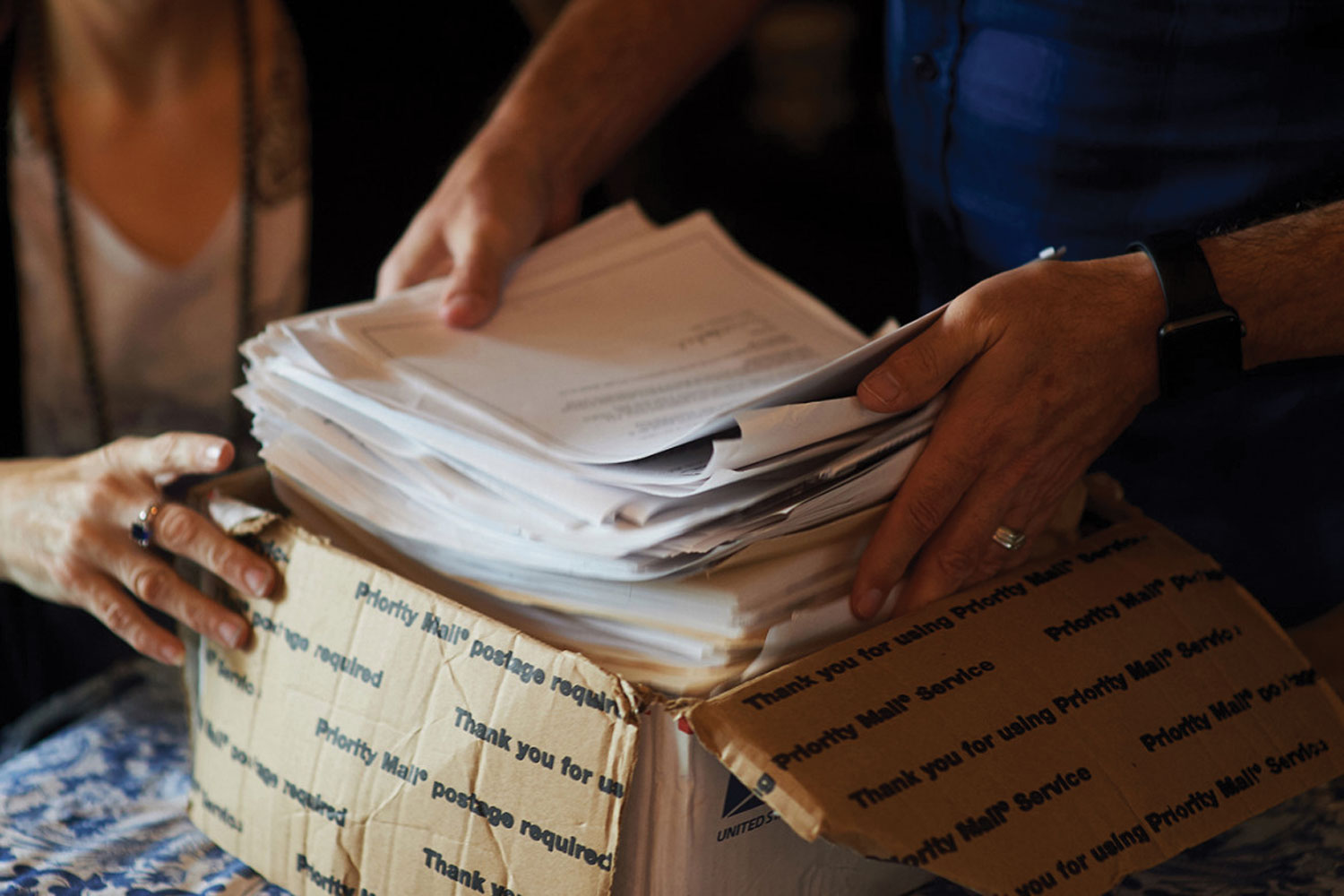

THE more than $34,000 in medical bills that contributed to Darla and Andy Markley’s bankruptcy and loss of their home in Beloit, Wisconsin, grew out of what felt like a broken promise.

Darla Markley, 53, said her insurer had sent her a letter preapproving her to have a battery of tests at the Mayo Clinic in neighboring Minnesota after she came down with transverse myelitis, a rare, paralyzing illness that had kept her hospitalized for over a month. But after the tests found she also had beriberi, a vitamin deficiency, Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield judged that the tests weren’t needed after all and refused to pay — although Markley said she and Mayo had gotten approval.

While Darla learned to walk again, the Markleys tried to pay off the bills. Even after Mayo wrote off some of what they owed, her disability and Social Security checks barely covered her insurance premiums. By 2014, five years after her initial hospitalization, they had no choice but to declare bankruptcy.

Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield spokesperson Leslie Porras said company “records do not indicate that Ms. Markley had tests authorized that were later denied.”

Markley said she never would have had the tests done if she had known insurance was not going to pay for them. “I feel for anyone that finds themselves in that predicament,” said Markley, a nurse who was pursuing her Ph.D. in education. “You can go from an upstanding middle-class American citizen to completely under the eight ball.”

The billing quagmire into which the Markleys fell is often called “retrospective denial” and is generating attention and anger from patients and providers, as insurers require preapproval — sometimes called “prior authorization” — for a widening array of procedures, drugs and tests. While prior authorization was traditionally required only for expensive, elective or new procedures, such as a hip replacement or bypass surgery, some insurers now require it for even the renewal of some prescription drugs. Those preapprovals are frequently time-limited.

While doctors and hospitals chafe at the administrative burden, insurers contend the review is necessary to ferret out waste in a system whose costs are exploding and to ensure physicians are prescribing useful treatments.

But patients face an even bigger problem: When insurers revoke their decision to pay after the service is completed, patients are legally on the hook for the bill.

Prior authorizations may now include a line or two saying something like: “This is not a guarantee of payment.” This loophole allows insurers to change their minds after the fact — citing treatments as medically unnecessary upon further review, blaming how billing departments charged for the work or claiming the procedure was performed too long after approval was granted.

In other cases, a patient will be told that no prior authorization is needed for a certain intervention, only to hear afterward that the insurer wanted one in this particular case. It then refuses to pay. Oftentimes, approval conversations happen primarily between the insurer and the provider — leaving the patient further in the dark when the bill appears.

The American Medical Association drafted model legislation to combat the problem for lawmakers to introduce, but the measure has not been widely picked up.

Martha Gaines, director of the Center for Patient Partnerships at the University of Wisconsin Law School, co-authored an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association on the issue and sees firsthand the time and money patients lose fighting such retrospective denials — for coverage they thought they had.

“How broken can you get?” she asked. “How much more laid bare can it be that our health care insurance system is not about health, nor caring, but just for profit?”

The push-and-pull of prior authorizations

Many physicians and health care providers consider the extra paperwork needed for prior authorizations a growing scourge that requires them to expand their staff to handle the back-and-forth with insurers. According to an American Medical Association survey released in 2019, 88% of providers reported that the burden of prior authorization has increased over the past five years, forcing them or their staff to spend an average of two business days a week completing them.

The process of prior authorization aims to establish medical necessity to prevent “unnecessary, costly, or inappropriate medical treatments that can harm patients,” according to Cathryn Donaldson, a spokesperson for the America’s Health Insurance Plans industry group.

It’s unknown how many patients get stuck with bills for prior approvals gone wrong. But retrospective denials have become only more common as prior authorizations have increased, said Dr. Debra Patt, an oncologist and chair of the Texas Medical Association’s legislative council.

Her practice has tripled the number of staff who deal with prior authorizations, and she said she is currently trying to get the Texas Medical Association to survey its members on the revocation topic after seeing its impact on her patients, one of whom she said recently had chemotherapy payments denied.

Donaldson said her insurance trade group realizes the process for prior authorizations could be improved and is working with tech companies to help streamline it for all involved. But she added that denials may be simple requests for more information.

“A denial usually occurs because the clinician may not have provided the documentation needed to show that the treatment is necessary,” Donaldson said. “Once that documentation is received, claims may then be approved.”

As insurers and providers argue over money, patients are often stuck in the middle.

After Rebecca Freeman’s insurer, Moda Health Plan, approved a genetic test for the Portland, Oregon, woman’s now 5-year-old daughter in 2018 to rule out a serious condition that could cause blindness, the insurer declined to pay after the test was performed.

Moda argued that the dates and billing codes didn’t match up with what was authorized. It told Freeman’s lab company, PreventionGenetics, it wasn’t going to pay, and, eventually, PreventionGenetics billed Freeman.

“Everyone is pushing the blame on everyone else, and I’m left holding the bag — there’s no recourse for the patient,” Freeman said. “Worst case for them is they pay what they were supposed to. You don’t get anything for all your stress and time.”

When Kaiser Health News first asked about the case, Moda spokesperson Jonathan Nicholas said it was still an active claim. “As soon as the lab provides us with correct information, we anticipate prompt payment,” he said.

But Freeman said Moda had denied five claims and appeals on the nearly $2,000 bill for more than a year.

Within days of KHN’s questions, Moda paid the bill.

The problem with legalese

Pharmacist Melita Pasagic of Fenton, Missouri, was told by her provider — who had called UnitedHealthcare, her insurer — that her and her husband’s genetic tests needed no prior authorization.

After the tests were performed, though, UnitedHealthcare told Pasagic it had deemed the tests medically unnecessary and would not pay for them. Later when she called, she said, the insurer cited a coding discrepancy. Although Pasagic spent hours on the phone appealing the decision, the insurer didn’t budge. The genetic testing company sent the $5,000 bill to collections.

“How can you deny anything post-service for medical necessity?” she said. “If it didn’t require a pre-review, why does it have a post-review?”

Pasagic said she plans to take UnitedHealthcare to court over it. The insurance company said the testing was never covered in the first place.

“While certain procedures, tests and drugs may not require prior authorization, individuals should still confirm that the services are covered under their benefit plans,” UnitedHealthcare spokesperson Maria Gordon Shydlo said.

Typically, there’s no penalty for insurance companies that play games with prior authorizations, Gaines said, calling denials and delays integral to their business model.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners has formed a working group to investigate the revocations following a presentation in December by Patt, of the Texas Medical Association. The Minnesota and Pennsylvania departments of insurance both said they had seen complaints regarding retrospective denials of prior authorizations. But quick fixes are unlikely.

“There’s no silver bullet for this issue, so we encourage consumers to remain vigilant,” said Katie Dzurec, acting director for the Health Market Conduct Bureau in Pennsylvania. “Ask questions, review documents and contact the insurance department.”

Markley hopes this doesn’t happen to more people.

“I wish people would understand that they are one illness away from totally losing everything they worked for,” Markley said. “I lost it all in a day.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.