FOR Asian Americans across the country, the events that unfolded on Tuesday, March 16 at three Asian-owned spas in Atlanta punctuated a mounting fear: the community isn’t safe.

A 21-year-old man entered three different massage parlors in the greater Atlanta area and gunned down workers and patrons, killing eight people in total, including six Asian women.

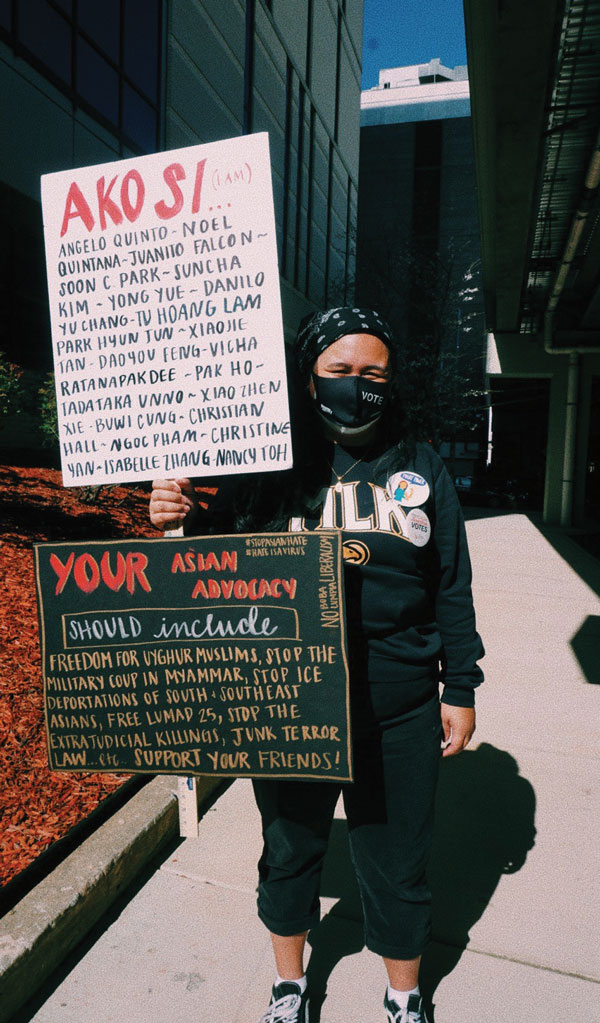

The event was shocking and reverberated beyond the Asian American community. #StopAsianHate began trending on Twitter. Celebrities and public figures of all races began echoing party lines of unity and stopping racism.

But a week after the Atlanta shooting, the outrage over anti-Asian racism is beginning to fizzle out in the mainstream. A grocery store shooting in Boulder, Colorado — which claimed the lives of 10 people — on Monday, March 22 reignited the broader issue of gun violence in America.

But the Asian American community doesn’t have the luxury of treating the Atlanta shooting and the disturbing rise in anti-Asian violence as last week’s news.

Just as Black Americans haven’t halted their goal in mitigating police brutality because “Black Lives Matter” isn’t trending or Central Americans who continue to advocate for humane practices at the southern border, the fight for racial justice and undoing dangerous misconceptions for the Asian American community doesn’t stop because it’s not the headline of the day.

Since February 2020, members of the Asian American community — and the greater Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community — have been acutely aware of the rise in anti-Asian harassment, violence and bullying with the onset of the coronavirus crisis.

According to the Stop AAPI Hate tracker, between March 19, 2020 and Feb. 28, 2021, there have been 3,795 reports of discrimination and assaults toward the AAPI community.

Physical assaults comprised the third-largest category of all incidents and women are 2.3 more likely to be harassed and/or assaulted, as the Asian Journal previously reported.

The virus was reported to have stemmed from China, so an erroneous relationship between the virus (which has taken millions of American lives and continues to disrupt millions more) and anybody who appears remotely Chinese was forged.

As such, Chinese were the largest ethnic group (42.2%) to report to the Stop AAPI Hate tracker, followed by Koreans (14.8%), Vietnamese (8.5%) and Filipinos (7.9%).

The statistics and number of reports are jarring and present a warped and dissonant view of the country that many Asian immigrants who relocate to the U.S. saw as a beacon of opportunity and upward mobility.

Political leaders, particularly Democrats like President Joe Biden, have argued that events like Atlanta are un-American. Biden made a point that his administration would combat hate and violence toward Asians, signing a measure proclaiming such on his first week in office.

“But for all the good that laws can do, we have to change our hearts. Hate can have no safe harbor in America. It must stop. And it’s on all of us — all of us, together — to make it stop,” Biden said in remarks on Friday, March 19.

Early reports from Big Media outlets — e.g. CNN, the New York Times and the Washington Post — framed the mass shooting as merely a mass shooting; the race and gender of a majority of the fatalities were a mere footnote, and it wasn’t until Asian Americans called out the incident as part of the longer string of attacks toward the community.

Taking a deeper look at the finer distinctions of anti-Asian racism, especially the details of each hate incident reported over the last year, represents a startling reality: historically and presently, racism and the experience of being a minority in America are seemingly inextricable.

Derogatory rhetoric promulgated by the previous administration and misnomers, such as the “China virus” and the “Kung-Flu,” has led many within the Asian American community to directly connect such expressions to the violence.

But while the hateful language may have spurred the thousands of reported incidents, they merely punctuate a dark and grimy history of anti-Asian attitudes that have made their mark in policy and society — a phenomenon that led to the persecution of Chinese, Filipinos, Japanese and South Asians that began in the 19th century.

For Tiffany Joy Garnace — an Atlanta-based Filipino American organizer who was born and raised in the American South — and the robust AAPI activist community in the region, the effort to combat anti-Asian racism didn’t begin with the Atlanta shooting, but it punctuated the scope of the problem.

“The Atlanta incident finally woke up the AAPI community that it can occur here and it’s frustrating for me as a community organizer. Prior to the shootings, we were trying to find community solutions,” Garnace told the Asian Journal.

She and Atlanta AAPIs have been trying to brainstorm preventative measures that could have helped recent victims like Thai American Vicha Ratanapakdee of San Francisco, Filipino and Chinese American Danilo Yuchang of San Francisco, Chinese American Pak Ho in Oakland, and the numerous elderly AAPIs who’ve been targeted at alarming rates for the last two months.

“It felt like a responsibility and indeed it felt like we failed our communities to keep them safe,” Garnace said.

“The sad thing is that there is this preconceived notion [that] in the South, especially in Georgia, these incidences happen only in areas with high Asian American populations like ‘California or New York’ or ‘cannot empathize because it has not [happened] to me or my family’ just to quote some people that I have heard in my spaces,” she added, noting that the AAPI community in Atlanta is “a beautiful conglomeration of all of these groups that people tend to forget [are] here and have been here.”

In the wake of the Atlanta shooting, vigils and demonstrations honoring the eight victims took place across the country. The rally in Atlanta on Saturday, March 20 brought together hundreds to the Georgia state Capitol to demand action and social and political change, particularly in the state.

Garnace was one of the many residents of all races who attended the vigil and rally which gave her “absolute chills.” But she was most astounded by the volume of Asian women who attended and what that represented.

“It is like we have been validated, seen and heard, for the first time,” Garnace remarked. “A lot of Asian women came out to the rally because they did not want to be seen as weak and fearful; having so many women come out to fight the intersection of race and misogyny was empowering. Also seeing the different groups of people that were not Asian there with us in support — I honestly teared up.”

The shooting also put a spotlight on how anti-Asian attitudes foment in ways that may not be as clear as discrimination toward other minority groups. Individuals from all Asian backgrounds shared how seemingly innocent things — like name-calling — fuel the fire of broader anti-Asian sentiments.

Garnace noted that seeing so many Asian American women, in particular, ignited the nuances of racist misogyny and “the fetishization of Asian women by non-Asian men.”

Filipino American Augelyn “Augee” Francisco — the indigenous Filipino owner of Kabisera Kape in New York City — shared with the Asian Journal how complex anti-Asian racism is and how a lack of education and cultural empathy can induce trauma that doesn’t really ever go away.

“Growing up, I had the same struggle, being Igorot,” Francisco shared. “My mother and the rest of us were targeted and bullied. That was my struggle when I was young and up to this day, I experience being called Chink, Ni-Hao, Virus, and looked down upon because of my slanted eyes and skin color.”

Francisco shared that recent events have reignited those memories, saying that, “I should not feel like that is ok. Because that is not ok. But I’ve lived with it for years in my life. This fight is for me and all my Asian sisters and brothers [a]nd for the future generation, there will be no more fight for equality and no more pain.”

Francisco was inspired to attend a vigil in New York City last weekend honoring the victims and rallying for the end of anti-Asian violence. Though many members of the Asian American community are pushing back against the stereotype of the docile Asian, Francisco sees gentleness as a strength and resistance tool for the AAPI community.

“We, Asians, are trained to be polite and obedient. We don’t believe in using violence, but we know how to use our forces: our strength is our unity, our respect, and our loving care,” Francisco said. “Those are the tools I’m planning to share and show as my participation. To awaken our sisters and brothers to halt the silence, to care and show love to our elders who get targeted, to our sisters who get murdered. Our respect to them doesn’t end at just paying respects at their wakes, but to pay respect to make sure that no more similar incidents will happen on our watch.”

Families of seven of the victims have organized GoFundMe pages, sharing the stories of their loved ones and raising funds for funeral and memorial expenses. A fundraiser was also started for Marcus Lyon, a survivor to help with counseling and other resources.

Georgia’s AAPI community is also urging supporters to donate to organizations on the ground, namely Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Atlanta, the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum, Asian American Advocacy Fund, and Asian Mental Health Collective, to name a few.

Members of the AAPI community who have experienced hate during the pandemic are encouraged to report the incident at: https://stopaapihate.org/reportincident. In addition to English, individuals can report in one of 11 languages, including Tagalog.