As Asian Pacific American Heritage Month continues on during a time of unprecedented fear and tension, a new documentary series from PBS celebrates the complex history of Asian Americans through stories of resilience in the face of persecution.

The five-episode docuseries — simply called “Asian Americans” — is the result of a ground-breaking program that spans the incredibly tumultuous 150-year history of Asians in America, a country that would have never been the way it is today without the efforts and exploits of immigrants and people of color.

The series, which premiered on Monday, May 11, follows the journeys of early Asian Americans from the mid-19th century when Chinese immigrants, who built half of the transcontinental railroad, became the first racial group to be banned from immigrating to the United States. This was a period when Asians had no political leverage or representation in government, rendering numerous uphill legal battles in immigration and equal protections.

“These Asian immigrants arrived at a time of great upheaval, reinvention and expansion. Asians will play a crucial role as a new America is being forged,” esteemed Korean American actor and co-narrator of the series Daniel Dae Kim says in the first episode “Breaking Ground” which details the late-19th century to the early 20th century, an important period in American history when Asian Americans helped set precedents in U.S. courts.

Five hours is certainly an iota of time if the objective is to recount the epic battles and achievements of Asian Americans, but the documentary makes good on its attempt to illuminate the complicated cultural, legal and political history of Asians in America.

As expected, the docuseries shares a bevy of stories of Asian American resilience and the strides early Asian Americans had to endure to ensure the equity and safety of future generations.

But the starkest moments of the docuseries lie in the stories of exploitation, the blatant examples of racism and the unnatural belief that certain races held rights and privileges that others do not.

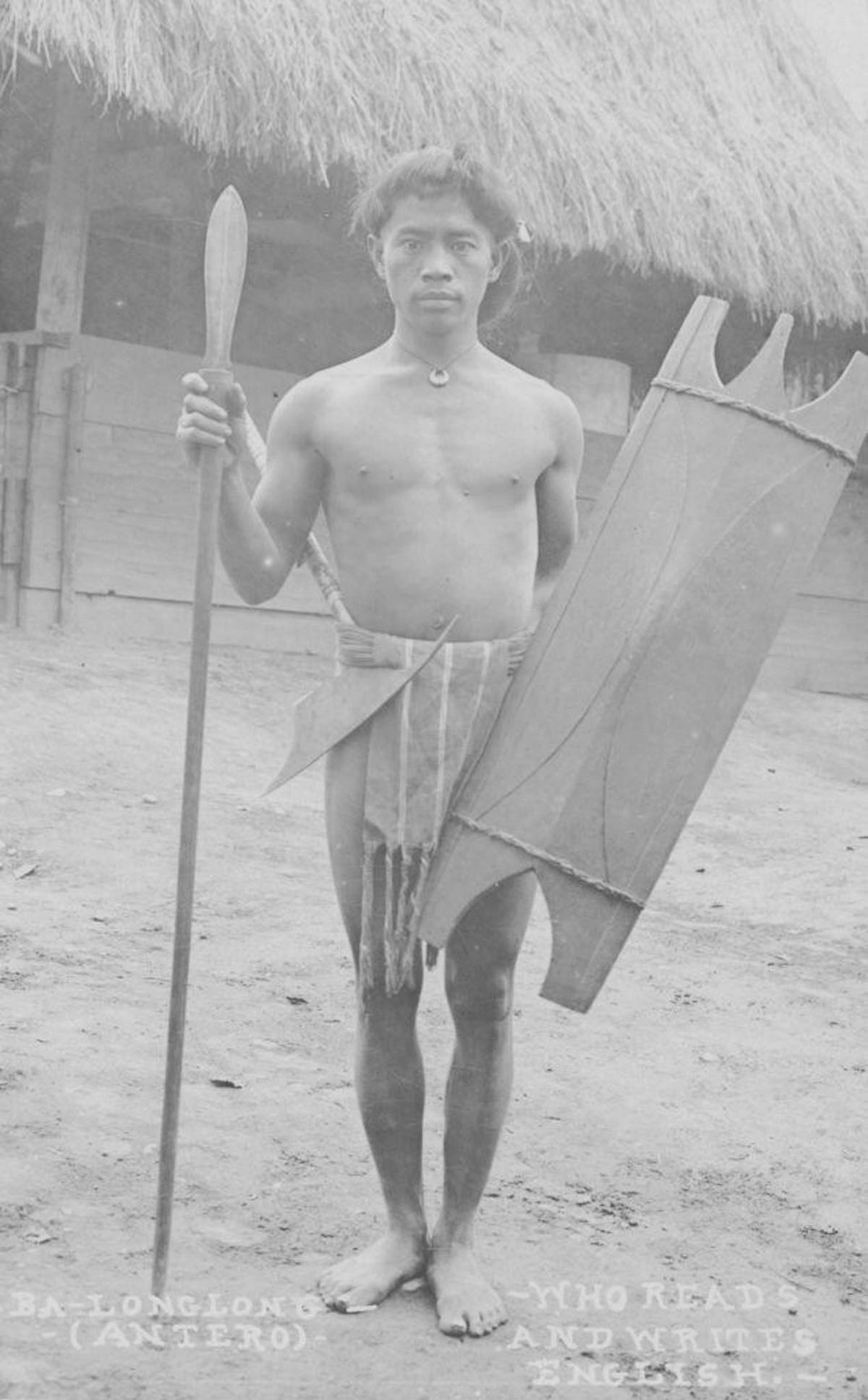

The series opens up with the story of Antero Cabrera, an Igorot man from the Philippines who was taken to the St. Louis World’s Fair in Missouri in 1904 as a part of the Philippine exhibit. Designed as a display of America’s imperial force, the Philippine exhibit wasn’t so much a true reflection of the Filipino people but a carefully curated interpretation of a “barbaric,” racially inferior community that needs the U.S. in its development.

This was a time when scientific racism was widely accepted among renowned anthropologists, who used pseudoscience to declare certain races inherently primitive — and would remain so without the help of American colonialism. By showcasing Cabrera and other Igorots acting in ways that would be considered subhuman — like a live eating of a canine in front of fair-goers — it was visual proof of this pseudoscientific myth.

“Anthropology at that time had an evolutionary aspect to it where they believed that there were races that were inherently barbaric and races that were inherently enlightened, and they rated according to skin colors,” said Mia Abeya, Antero Cabrera’s granddaughter, adding that the exhibit was “a way for Americans to show that they were superior to the rest of the world.”

Despite the humiliation, Cabrera soldiered through the exhibit and other like anthropological displays to make money to send to his family in the Philippines, eventually making enough to live a stable life. But the project created a lasting impression of this “exotic” country in Southeast Asia, a way to show people that “[t]hese are savages. This is how they look and this is how they live. Americans just saw them as objects of display in those human zoos.”

Landmark immigration and education cases — like Tape v. Hurley in 1885, which declared the exclusion of a Chinese American student based on her ancestry from a public school unlawful — offset the many, many personal stories of descendants of early Asian Americans and those who lived to tell their experiences.

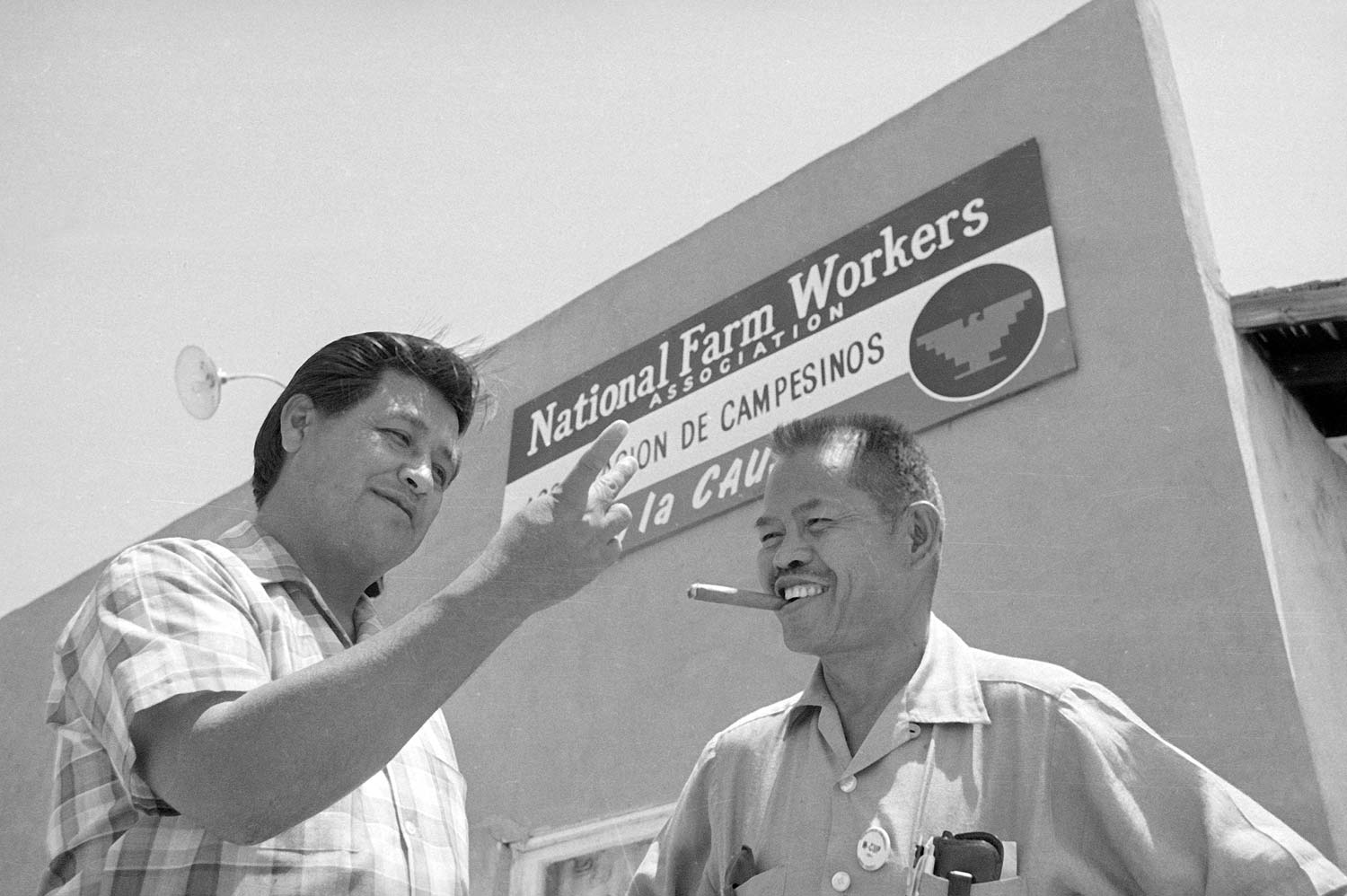

The docu-series then flows to the labor movement of the 1930s led by Larry Itliong and Filipino farmworkers, the internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War and legislative achievements like the Voting Rights Act of 1952 which gave Asian Americans the right to vote. Cultural landmarks like the increased representation of Asian Americans in Hollywood following the regular practice of yellowface) and the rise of Asian American entrepreneurship.

And it wasn’t just the legislative victories that initiated the emergence of the growing and hustling Asian American community. From the construction of the transcontinental railroad, to the cultivation of California’s farms, to the technological innovations in the auto industry, Asian Americans are inextricable from the overall narrative America.

Simply put, the docu-series proves that America wouldn’t be what it is today without the labor and assimilation of Asian immigrants who underwent enormous trauma and sacrifice to cultivate a life for the Asian American. It redefines what it means to be American, that it isn’t based on race or what a piece of paper dictates: it is a mindset and unyielding work ethic that makes you American.

But the struggles faced by early Asian Americans are not exclusively things of the past.

As films about slavery and the 1960s civil rights movement attempts (and often, fails) to provide a distant memory of America’s ugly past — as if to say, ‘’Look how far we’ve come from blatant racism and discrimination — it may be grating to celebrate the victories and achievements of the Asian American community while undergoing a new wave of anti-Asianism in the age of COVID-19.

The current generation of Asian Americans, millennials and younger, especially, were fortunate enough to be born after the regular lynchings of Chinese Americans at the turn of the century as well as the gruesome murder of Vincent Chin in 1982. However, although it may seem dampened by the expanding awareness of social justice and activism, the Asian American community faces a new wave of discrimination.

The only difference between then and now, however, is a vigorous, outspoken community of lawmakers, celebrities and other Asian American public figures who are leading the charge against anti-Asian racism propped up during this pandemic.

“I cannot think of a more important conversation to be having right now,” PBS Newshour correspondent Amna Nawaz said last week during a digital town hall. Nawaz added that “2020 was supposed to be a consequential year for Asian Americans” noting the crucial 2020 election and the census.

“But as we know, the pandemic changed everything, and now 2020 stands to be consequential for very different reasons,” she remarked.

It’s a point that the documentary series illustrates in its final episode called “Breaking Through” that progress isn’t a linear journey. There are going to be pitfalls, and even though we’re living in a time of unprecedented success and increased awareness of social justice, times like these prove that society isn’t a perfect construct, and there will be periods upon which resilience and strength of character will be tested.

As journalist and activist Helen Zia put it in the final episode of the series: “History has a way of moving in cycles, and if we can learn from history, even a little bit, we can avoid repeating it. But even better than that, we can find the things that have moved civilization forward and have led to greater progress, and if we learn from that, we can really move ahead.”

“Asian Americans” is available to stream now on PBS apps as well as its website.