Duterte extends last minute travel ban that left airport staffers, travelers in a

confusing scramble

LIKE countries across the world desperate to mitigate the coronavirus, the Philippines instituted a new ban on international travel from certain countries where the new strain of the virus has been detected.

The latest ban includes and applies to foreign travelers coming from Pakistan, Jamaica, Luxembourg, Oman, mainland China, United Kingdom, Denmark, Ireland, Japan, Australia, Israel, The Netherlands, Hong Kong, Switzerland, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Lebanon, Singapore, Sweden, South Korea, South Africa, Canada, Spain, United States, Portugal, India, Finland, Norway, Jordan, Brazil, and Austria.

Specifically, the mandate applied to the U.S. starting on Jan. 3.

The Philippines’ new ban comes as more of the world is becoming more exposed to a new variant of SARS-CoV-2 and earlier this month, the new variant (which was first found in the United Kingdom) was found in the Philippines.

To date, the Philippines has the second-highest number of COVID-19 cases in Southeast Asia behind Indonesia, according to the World Health Organization.

“Huwag na kayong bumili ng ticket kung galing kayo sa mga lugar na iyan at hindi kayo Pilipino at darating kayo on or about the 15th of January (Don’t buy plane tickets if you are from areas included in the travel ban and if you are not Filipinos; also, if you wish to come here on or around the 15th of January),” Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque said to foreign travelers from the temporarily banned countries in a press briefing last week.

For many travelers, the ban simply halts immediate plans to travel, forcing people to reschedule and request refunds for any purchased plane tickets: another inconvenience in a time colored by inconveniences.

And the Philippine government has said that it wasn’t planning on barring Philippine-born kababayan from entering the country: Roque said on Jan. 14, “Nanindigan na po ang Presidente walang Filipino na pupwedeng mapigilang umiwi (The President has stood form that no Filipinos will be barred from coming home).”

But the ban reflected dissimilar sentiments for the dozens of travelers who arrived at Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA) on Jan. 3 with unsettling news.

“They took our passports and gave us no information.”

Ms. Almares, who declined to give her first name for privacy, was en route to the Philippines on the same day that the travel ban included the U.S. The Filipina expatriate — who was born in Batangas and moved to Los Angeles with her family to escape martial law in the 80s — had been adhering to pandemic public safety rules.

But when she found out her grandmother in Manila had been sick with nobody to look after her, Almares took the initiative to go back home and care for her lola.

“I actually didn’t buy a return ticket because I planned to stay for as long as possible to care for her and provide any kind of financial aid and be her primary caregiver,” Almares told the Asian Journal in a recent phone interview.

“She’s my only living lola and I call her my last ancestor on my mother’s side so I definitely wanted to take care of her, and unfortunately there are no other family members so I made the choice and set out on this journey,” Almares added, saying that she was able to make the trip financially since airline tickets are at an all-time low (about $400 for a one-way journey, she said).

Ahead of her flight on Jan. 3, Almares prepared all the documents needed to prove that her travel was considered essential. Since the beginning of the pandemic, governments across the world have imposed travel bans on foreign travelers with varying degrees of severity and rigidity.

The Philippines had previously imposed travel bans that allowed those who were mid-flight amid the ban’s implementation to quarantine for 14 days in a safe location and either allow them to stay in the Philippines or travel back home.

Travel advisories posted at that time by the Philippine Embassy and U.S. and Philippine immigration noted that Filipinos were able to travel back to the Philippines if they provided documentation of essential travel (in Almares’ case, proof that her grandmother was hospitalized). Through the Philippines’ Balikbayan Program, travelers were also allowed to travel if they provided their old Philippine passport or a copy of their birth certificate.

“All of us were solely on that flight because of the Balikbayan Act, so you know we were prepared,” she said.

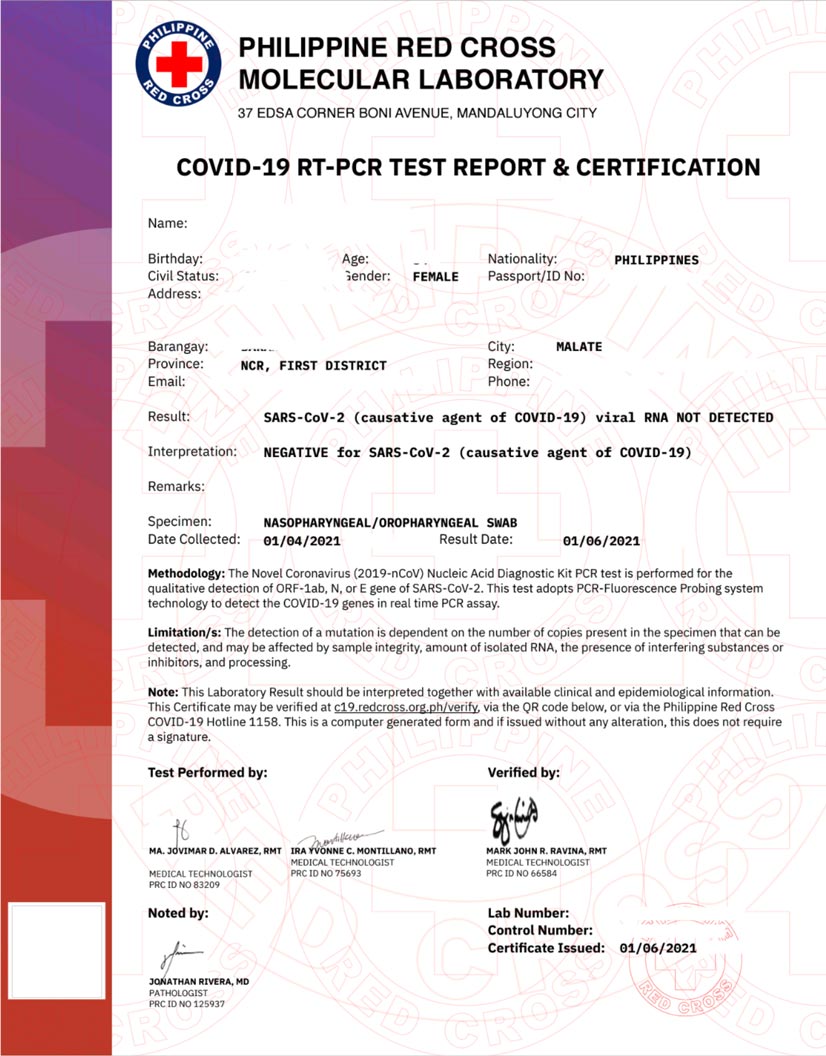

But in the case of Almares and the dozens of travelers on her flight, airport staff and security were ill-equipped in the face of the new travel ban. According to Almares, once she landed, travelers were notified of the new ban. She still had to pay the $80 USD for a swab test through Philippine Red Cross, but once they reached immigration, they were notified that the new ban included the United States.

But Almares’ flight was in a gray area because they had a layover in Guam, meaning that in Guam, United Airlines could have notified them of the ban and that they were unable to enter the Philippines, but because “it said Philippines on our passports,” the airline let them continue on to Manila.

According to the Almares, an airline official told them that the airline could not “prevent you from going to your birth country,” and that they had certain birthrights as Philippine-born Filipinos.

“But that day [at NAIA], I guess we didn’t,” Almares said.

At the immigration kiosk at NAIA, Almares said that airport security told travelers that they could not travel any further, reportedly confiscated their passports with no explanation, and stuck the travelers in a holding room at the airport.

“Mind you, I’m coming off an almost 14-hour flight. It’s 10 p.m. when we landed, nothing is open to eat because airport restaurants were closed, and we’re put into this holding room that had no beds, no showers, no TV and it was just completely uncomfortable and we had no idea what was happening because nobody gave us any information, even when we asked,” Almares recounted.

The next day, they were shown the government mandate that banned visas from countries that appeared on the list of barred nations. The mandate had been implemented while Almares’ plane was in the air, but airline security did not announce plans to quarantine the travelers in a legitimate way or provide any accommodations beyond the holding room.

The passport confiscation, in particular, made Almares uncomfortable: “They had them in backpacks, not secured whatsoever. There were already incidents of stealing throughout those two days so I was worried something might happen to my passport.”

Almares said that throughout their detainment, she befriended fellow travelers and offered to help those who didn’t have any internet connection by giving what information she can find. One of the travelers she got to know was an 85-year-old Filipina and her grandson (who is autistic) who were worried that they would not be able to go home.

The situation was frustrating, stressful and scary for many of the travelers, Almares said.

At one point, she began to reckon with the fact that she wouldn’t be able to see her grandmother and the plans she had to care for her would never come to fruition. Unlike previous instances where travelers were in mid-air when a ban was imposed, there were no moves to quarantine the travelers once they touched down.

They ended up spending “48 hours going into 72 hours” in the holding room, Almares said, adding that they all had to keep their face masks and shields on.

All the while, Almares and others tried to call embassies and consulates in an effort to have a government body advocate on their behalf, but those communication attempts didn’t amount to much.

Almares decided to confront airline staff and security about the situation, asking for any answers to the questions that she and others had: Are we able to get a flight back home?

If so, when will we be going home? Do we have to pay for a new boarding pass? Are we going to be quarantined? How long are we to stay in the holding room?

But she received the same, unsatisfying answers every time: “We’re working on it, and we’ll give you information once we receive it.”

At the peak of her frustration, Almares pulled out her phone and began recording her interactions with airline security, demanding answers and letting staff know about the “unfair” treatment the travelers are receiving. On Filipino Facebook groups, she began detailing in real time her experience, providing updates to the nearly three-day saga.

At one point, according to Almares, an airline staff member told her that she was being “maarte (dramatic),” and tried to get her to calm down.

The Philippines is a country that for the last few decades has poised itself to be a tourist destination to the Western world that rivals Bali, Indonesia; Phuket, Thailand and other tropical locales in South East Asia.

The tourism effort has kickstarted many a campaign to attract Western travelers (i.e. wealthy white folks with a hunger for wanderlust) to places like Boracay, Surigao and Palawan — Philippine locales that represent the natural beauty of the land that conveniently hides the less savory characteristics of a country that is still considered Third World.

It’s not lost on Almares that the hospitality that the Philippines touts in its tourism campaign seemed to be absent the day she and the dozens of other members of the Filipino diaspora and expats were forced into the purgatory of an NAIA holding room with no help from airport and airline staff and the U.S. Embassy in Manila.

Of course, she’s understanding of the usual circumstance of the pandemic and the new viral strains that have put the entire world on high alert. But the “inhumane” treatment that she received from the staff and security and the unusual protocols were far from the realm of acceptable conduct, even in a pandemic.

More than two days after she had first landed at NAIA, Almares said that the frustration and confusion had pent up and she decided to make a stand. After retrieving her passport from the backpack where all the passports were stuffed into, she decided to book a flight over the phone through United Airlines and try to get back home, but airline security at NAIA told her she couldn’t do that.

Originally she wanted the 2 p.m. flight through Nippon Airways (United Airlines’ sister airline), but they were given the 11 p.m. flight.

“I had to release some pent-up anger and the only way I could do that was just to voice myself and I told them, ‘What happened to kababayan? What happened to bayanihan, the welcoming of countrymen?’” Almares recalled. “The Philippines has a history of treating its own citizens poorly and if they were to anger a large number of people who are trying to travel to the Philippines, they could get a lot of backlash for this.”

She understands that many of the staff she interacted with at NAIA weren’t ultimately the ones to blame and that they were just as much in the dark as she was, but it doesn’t excuse what she went through.

“I told them, you know, that I know that they’re just doing their jobs but they’re getting so little pay and I said, ‘You’re doing this and it puts so much burden on you,’ because if I had lost my passport when they confiscated it, they would be in a lot of trouble,” Almares said. “I was trying to reach their hearts and let them know that this situation doesn’t help anybody involved.”

Eventually, Almares and her fellow travelers were given free flights to go back home, more than two days of sitting in the NAIA waiting room. She was able to get a refund for the ticket she purchased, but the frustrating ordeal offered no relief. The 85-year-old lola she befriended had stayed behind because she couldn’t physically travel again on such short notice, so Almares offered to help the grandson get home safely.

The current ban on travelers in the Philippines was extended two weeks and is now in effect until Jan. 31, according to Malacañang.

“I came out of that experience feeling very disconnected,” Almares said, who was able to arrive back in Los Angeles safely. She described feeling a strange betrayal from her birth country, noting its sensitivity to criticism.

“You cannot criticize the Philippine government at all. You could be blacklisted, but honestly, I’m fine if they blacklist me for speaking about what happened. They are vulnerable and the [Philippine] government can change the law on a whim, we know this. I just wanted people to know that people who want to come to the Philippines, that your health and physical being could be put in a very compromising situation,” she added. (Klarize Medenilla/AJPress)