“WE need to start a conversation.”

For the past few weeks, this has been the party line among Filipino Americans who recognize the deeply rooted racism embedded into the community. Now, they’re having that conversation.

On Saturday, June 13, FilAm Arts hosted a “FilipinX For Black Lives” livestream on Facebook, during which prominent Filipino American writers, journalists, academics and artists started the uphill climb of undoing the complicated ways that the Filipino community either intentionally or unconsciously contributes to anti-blackness in flagrant and discreet ways.

Just like the current COVID-19 pandemic, the current upheaval related to reexamining the priorities and purpose of law enforcement in the United States is demarcated by phases. The first phase happened roughly in the immediate aftermath of the unlawful killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, an event that shocked the nation and world and catalyzed a global movement to end police brutality.

In a matter of weeks, the movement blossomed from protesting police brutality to tackling the historic patterns of anti-black racism across public-facing entities and other ethnic communities.

Within the last few days, notable black deaths in California that have been reported as lynchings — Malcolm Harsch, 38, who was found hanging in Victorville and Robert Fuller, 24, in Palmdale — have surfaced, signaling further urgency to address and undo the many, many ways black individuals are persecuted.

Over the course of two hours, panelists discussed a wide range of topics ranging from the effects of colonialism to contemporary microaggressions.

“Making sure Filipinos educate other Filipinos and understand that this task of undoing anti-blackness doesn’t rest solely and squarely on the shoulders of African Americans,” Janet Stickman, professor and spoken word artist, said in the opening of the livestream that spanned two hours.

Rather than cower defensively and sidestep the opportunity to right wrongs, it is imperative that Filipino Americans take a hard look at how we react to anti-black racism and the ensuing outcry: do we justify the myth that racism is nonexistent, or do we validate the experiences of black Americans? Or, the worst-case scenario, do we knowingly act as a buoy to anti-blackness?

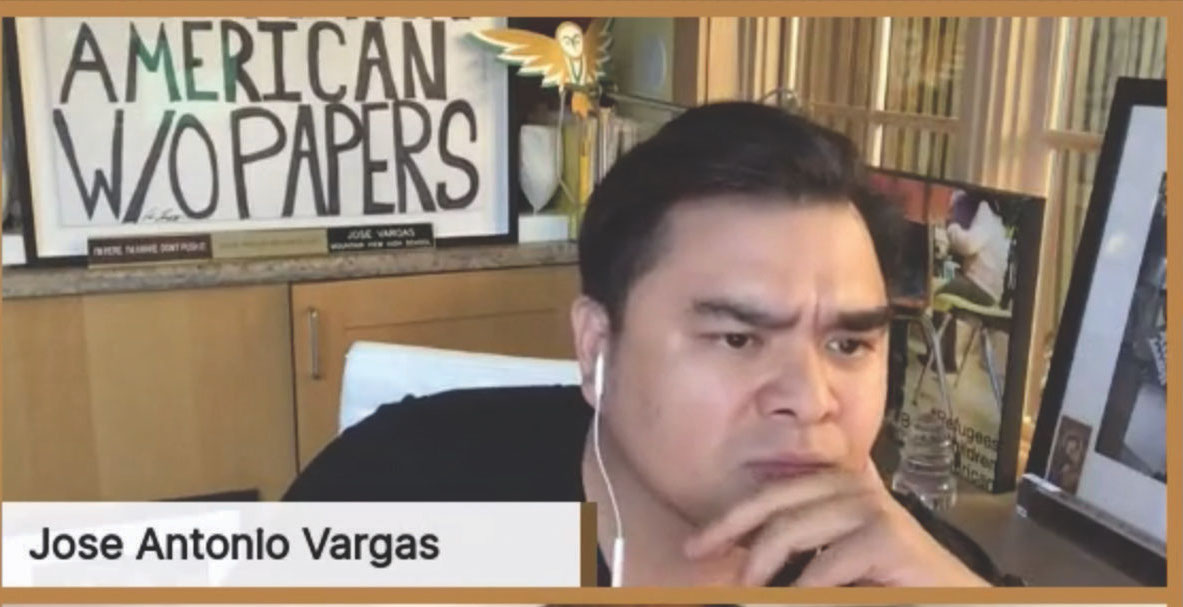

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and Define American founder Jose Antonio Vargas acknowledged the psychological and emotional difficulties in coming to terms with community-wide patterns of antiblackness and colorism, pontificating on the overvalue the community gives to the superficial.

“We can talk about what makes us proud about our culture and our people, but declaring that black lives matter in a culture that idolizes white skin requires self-examination,” Vargas explained, calling for a community-wide devaluing of entertainers, Miss Universe contestants and materialism that, instead, uplifts Filipino academics, intellectuals and activists.

The root of anti-blackness within the Filipino community isn’t centered around an exact moment in history. Rather, it manifested slowly from the colonial periods when imperialists would stir up colorist attitudes about dark skin and fair skin, according to Dada Docot, an assistant professor of anthropology at Purdue University.

Docot added that these attitudes carried over to intercultural relations within the U.S. Navy in which “Filipinos and black people were pitted against each other in a system that was racist to both groups in the first place.” Docot shared that in 1932, the head of investment training of the U.S. Navy fomented anti-black sentiments by claiming that Filipino sailors were cleaner and more well-behaved than their black counterparts.

According to Docot, this instilled a subconscious desire for approval from and alignment with white Americans, a seed that sowed the model minority myth.

For children who have both Filipino and black ancestry, these issues present a critical quandary. Within the Filipino community are a significant number of Filipinos who identify as black; one in five Filipino Americans identify as multiracial, according to the United States Census Bureau.

“It’s important to think through the ways we can incorporate a more diversified [news] feed and how we consume our news,” said Stephanie Chrispin, a half Filipina and half Haitian organizer and communications manager.

Crispin recognized the emotional toil it’s taking on non-black folks to re-examine their behaviors, acknowledging that “being anti-racist” and being newly awoken to the horrors of racism “may be exhausting, but for many of us, this is stuff we’ve been doing our whole lives.”

And, again, that starts with reinforcing healthier news and media consumption and expanding the community’s knowledge and awareness of black issues and advocacy. Because Crispin said, it may be exhausting to shine a light on the community’s intercultural short-comings, but it’s a cakewalk compared to the real traumas black Americans have faced since the arrival of the first African slaves in 1619.

Vanessa Carr, a civic engagement organizer of LEAD Filipino who is half black and half Filipina, mentioned that “it is incredibly encouraging” to see the Black Lives Matter movement and issues related to it are now topics being discussed across the Filipino community.

Like many other half Filipino and half Black Americans, Carr recounted the microaggressions she faced because of her mixed-race heritage, especially from other Filipinos who reinforced colorist attitudes regarding her skin tone and hair. And even though she credits her parents as encouraging her to embrace both parts of her heritage, the remarks made a lasting impression.

“It’s a weird thing to grow up because my parents never discouraged me from loving both sides of myself, but you know there were those in the community who’d make comments that they didn’t realize would stick to you and hurt you,” Carr shared.

Solidarity beyond police brutality

Although this is a moment of awakening for the microaggressions and horrors that black folks face, Stickman reminded Filipinos to recognize the accomplishments of black Americans, whose impact on American culture and politics is profound.

The ultimate goal of Filipinos for Black Lives goes beyond rectifying systemic bias and discrimination. It’s about recognizing anti-blackness within the Filipino American community, how it contributes to anti-blackness in general and to foster a community that recognizes that black lives matter outside of highly publicized extrajudicial killings.

“Please, please don’t wait until black people die before you pay attention to our value,” Stickman added. “In addition to educating ourselves about the injustice experienced by African Americans over the centuries, it is also important to make sure that we learn and teach about the accomplishments, the contributions, the triumphs, the innovations of black people over centuries as well.”

Black culture has been instrumental to Filipino culture, especially. Hip-hop, rap, soul, R&B, rock & roll and other musical genres that have roots in the black community continue to inspire kids of the Filipino diaspora. Moreover, the love of balladeers and the insurmountable value that Filipinos place on singing acumen largely comes from legendary black voices like Whitney Houston, Chaka Khan, Nina Simone and Aretha Franklin.

Professional black athletes, especially those in the NBA, are held up as idols the world over — Kobe Bryant’s prolific influence on Filipinos across the world alone speaks volumes of black influence — while contemporary gay and drag culture owes its prosperity to the black queer community and the ballroom scene of the 1980s.

Squaring the inextricable impact black culture has made on Filipino culture with the racist tendencies of our less informed community members is a predicament, a kind of collective cognitive dissonance between idolizing and gaining influence from prominent black athletes, artists and celebrities while simultaneously remaining quiet over (or trying to justify) the extrajudicial killings of unarmed black civilians.

In an extended spoken-word sequence, Filipina American DJ and rapper Kuttin Kandi reminded Filipinos — who engage in these universal avenues, especially hip-hop and rap, paved by black creatives and athletes — of the historical significance of the genre that goes beyond certain aesthetics.

“We are merely guests, invited to contribute to hip hop culture, which means we have a responsibility to do justice by hop-hop as was created during a time of oppression upon black and brown youth of the South Bronx,” the DJ preached, adding that affirmation of black lives and the identity intersections therein is the only way forward.

“It means that for those of in hip-hop, we must be pro-black and co-conspirators to black liberation movements as well as the anti-homophobic, anti-transphobic, anti-queerphobic, anti-ableist, anti-fatphobic,” she continued. “This is about the movement for black lives, this is about how we leave love for ourselves and one another with a righteous rage alongside our black siblings, for their freedom and for our collective liberation.”

Reversing racist tendencies is an uphill battle that requires the whole of the community’s effort, each panelist explained. Once we have recognized what anti-blackness looks like, then we can move forward by keeping each other in check and calling out relatives and friends when they exhibit anti-black behaviors and attitudes. And, through that, we can stand confidently in solidarity with the black community.

“At this historic moment, what does it look like and feel like in some way to engage those parts of our culture? What are each of us with our own privileges willing to risk? How uncomfortable are we willing to get?” Vargas posed.