Before the midterm elections heated up, dozens of drugmakers had already poured about $12 million into the war chests of hundreds of members of Congress.

Since the beginning of last year, 34 lawmakers have each received more than $100,000 from pharmaceutical companies. Two of those — Reps. Kevin McCarthy of California, the House Republican majority leader, and Greg Walden of Oregon, a key Republican committee chairman — each received more than $200,000, a new Kaiser Health News database shows.

Republicans are not the only beneficiaries of drugmaker largesse, however. In California, seven of the top 10 recipients are Democrats, including Rep. Linda Sanchez, whose $144,500 in pharmaceutical contributions puts her second to McCarthy among Golden State congressional members. Rep. Scott Peters, also a Democrat, tallied more than $100,000 in drug company donations, as did Rep. Mimi Walters, a Republican.

California’s senior U.S. senator, Dianne Feinstein, a Democrat, has received $35,000 in pharmaceutical money since the start of 2017. The state’s junior senator, Democrat Kamala Harris, has received nothing from the industry. In April, Harris joined other Democratic 2020 presidential prospects vowing not to accept money from corporate PACs.

As voters prepare to go to the polls, they can use a new database, “Pharma Cash to Congress,” tracking up to 10 years of pharmaceutical company contributions to any or all members of Congress, illuminating drugmakers’ efforts to influence legislation.

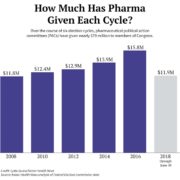

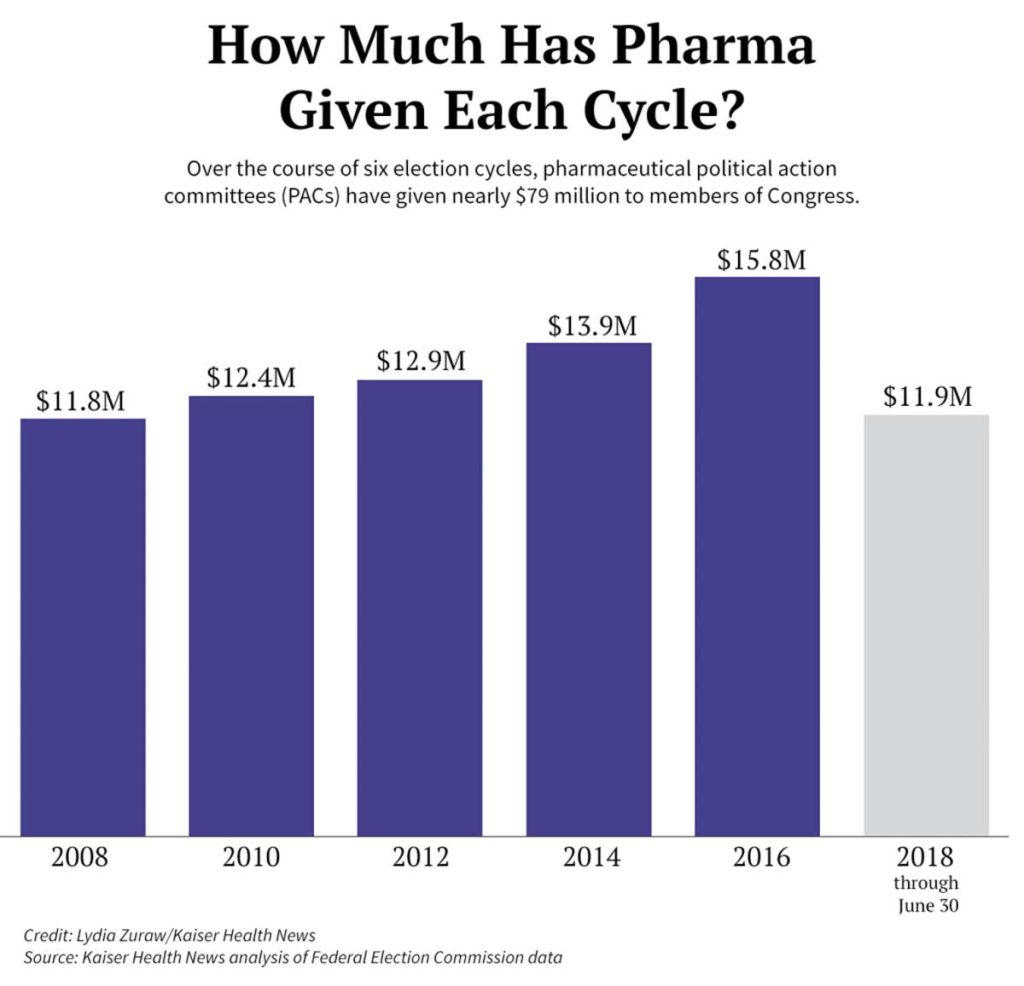

The drug industry ranks among lawmakers’ most generous patrons. In the past decade, members of Congress have received $79 million from 68 pharma political action committees, or PACs, run by employees of companies that make drugs treating everything from cancer to erectile dysfunction.

Drugmakers’ campaign contributions have reached record-breaking levels in recent years as skyrocketing drug prices have become a hot-button political issue. By June 30, 52 PACs funded by pharmaceutical companies and their trade organizations had given about $12 million to members of Congress for this election cycle. It is unclear whether drugmakers will top their previous 10-year record of $16 million, given during the 2016 election season.

While PAC contributions to candidates are limited, a larger donation frequently accompanies individual contributions from the company’s executives and other employees. It also sends a clear message to the recipient, campaign finance experts say, one they may remember when lobbyists come calling: There’s more where that came from.

The KHN analysis shows that, as in the case of California, pharmaceutical companies tend to play the field, giving to a wide swath of lawmakers on both sides of the aisle.

The drug industry favors power. Since the beginning of 2017, drugmakers contributed to 217 Republicans and 187 Democrats, giving only slightly more on average to Republicans, who currently control both chambers of Congress. This was also the case for Democrats during the 2010 election cycle, when they controlled Congress.

As with other industries, drugmakers tend to give more to lawmakers in leadership roles.

For example, Rep. Paul Ryan, a Wisconsin Republican, became speaker of the House halfway through the 2016 election cycle, prompting drugmakers to pour $75,000 more into his war chest than they had the previous cycle.

Money also tends to flow to members of congressional committees with jurisdiction over pharmaceutical issues that can affect things like drug pricing and FDA approval. Walden, a nine-term Republican congressman, has watched his coffers swell with help from drugmaker PACs since he became chairman of the powerful House Committee on Energy and Commerce in early 2017.

With six months to go in the 2018 cycle, Walden had already raised an additional $71,000 over the 2016 cycle — or 11 times more than drugmakers gave him a decade ago.

Asked to comment on the increase in Walden’s contributions from drugmakers, Zach Hunter, his committee spokesman, called attention to Walden’s work to lower prescription drug prices and said “no member of Congress has done more” to end the opioid crisis.

Pharmaceutical company PACs also gave to dozens of other members of committees, such as the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. And they appear to target congressional districts that are home to their headquarters and other facilities.

The PAC for Purdue Pharma, the embattled opioid manufacturer, gave to only a handful of members this cycle. However, it focused much of its giving on lawmakers from North Carolina, its headquarters for manufacturing and technical operations.

This election cycle, 28 percent of lawmakers did not receive any contributions from pharmaceutical PACs.

Under federal law, corporations cannot donate directly to political candidates. Exploiting a common loophole, they instead set up PACs, funded by money collected from employees. Those PACs then donate to campaigns, which are free to spend that money as they wish on necessities like advertising or campaign events.

Campaign contributions tell only part of the story. Drugmakers also spend millions of dollars lobbying members of Congress directly and give to patient advocacy groups, which provide patients to testify on Capitol Hill and organize social media campaigns on drugmakers’ behalf.

A previous investigation by Kaiser Health News, “Pre$cription for Power,” examined charitable giving by top drugmakers and found that 14 of them donated a combined $116 million to patient advocacy groups in 2015 alone.

And like other industries, pharmaceutical companies wield their political power in ways veiled from the public, giving to “dark money” groups and super PACs — independent groups barred from directly donating to or coordinating with campaigns — bent on swaying lawmaking.

Brendan Fischer, who directs federal reform programs at the Campaign Legal Center, cautioned that a campaign contribution from a corporate PAC does not directly translate into a vote in the drugmaker’s favor.

“Contributions help keep the door open for company lobbyists,” he said.

_

Kaiser Health News data editor Elizabeth Lucas contributed to this story.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.