Unpacking the history of social justice and revolution in the Filipino American community and cultivating a more inclusive, informed future

EARLIER this year, Filipino Americans from all walks of life took to the streets in protest of racial injustice and systemic discrimination following the high-profile murders of Black Americans.

| Photo courtesy of @hazelsunday/Instagram

Filipino Americans all across the country joined protests and rallies decrying the systems within American law enforcement that have allowed officers who have shot and killed unarmed people, particularly Black individuals, to bypass the justice system.

Skeptics, critics and disengaged Filipinos alike all continue to question: Why are you getting involved in an issue that has nothing to do with Filipinos?

For many Filipinos in social justice circles, that assumption couldn’t be further from the truth.

This year, the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS) themed Filipino American History Month 2020 around the concept of social justice because of the pervasiveness of oppression that the Filipino American (and global Filipino) community has endured for centuries.

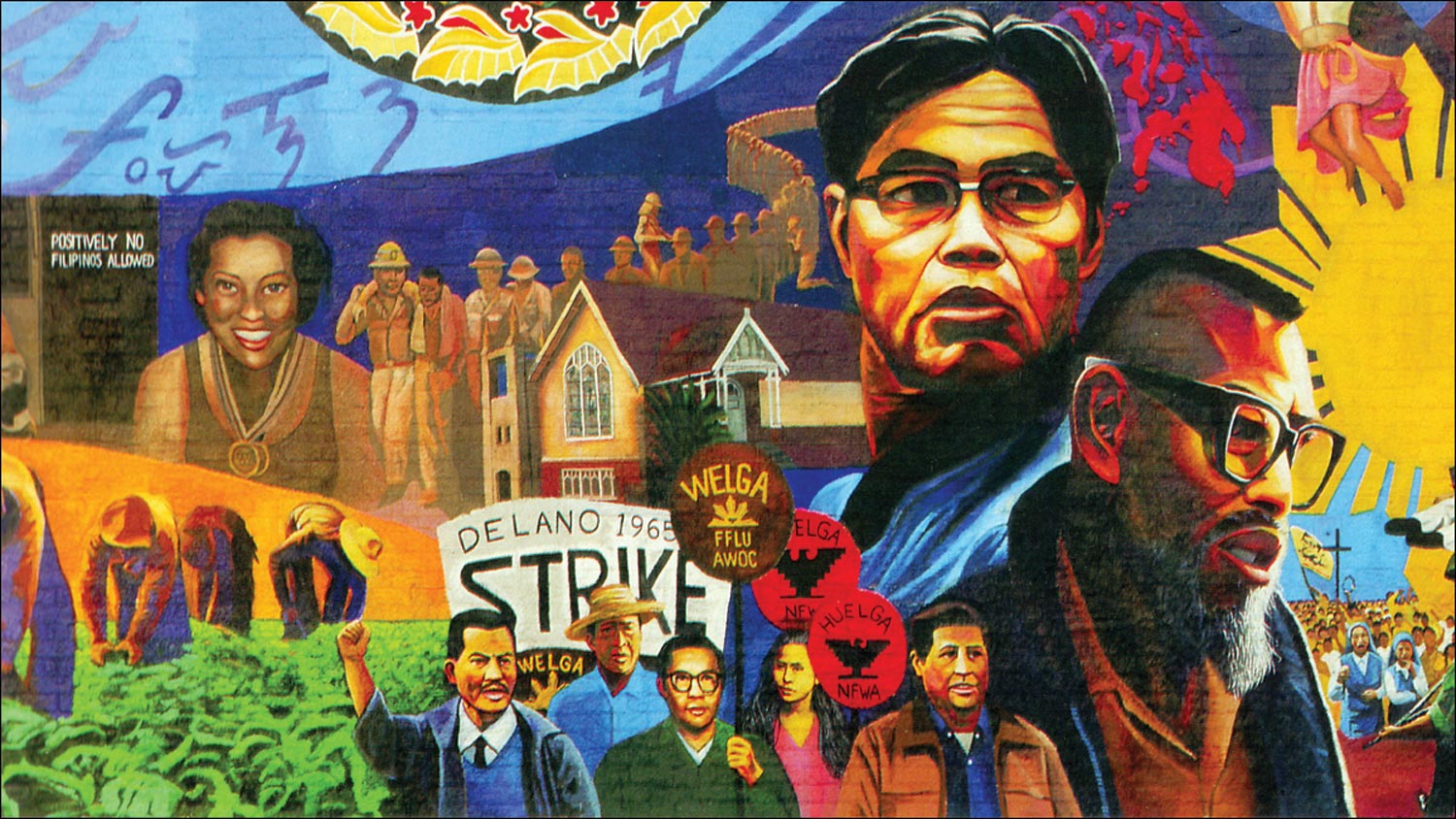

“We choose this theme to highlight the myriad ways Filipino Americans have participated in social justice movements, including but not limited to, the United Farmworkers Movement, the fight for Ethnic Studies, Hawaii Sugar Plantation strikes, Washington Yakima strikes, and Anti-Martial Law Movements across multiple decades,” the organization said.

In June during an interview about the Filipino community’s role in civil rights, Filipina American organizer Jollene Levid told the Asian Journal that “[e]very mass movement in our history that has changed the way a state or government or a country has been run, including the Philippines and the toppling of Marcos. People have found a way to contribute in ways that go beyond what you see as a normal protestor on the street.”

Although contemporary Filipino Americans enjoy a relatively comfortable life, the year 2020 presented them with stark reminders that as long as racism, political tyranny and propagandistic forms of communication exist, persecution, in any form, is just around the bend.

“This living nightmare that we’re living in now is not new,” Filipino American lifelong activist Kalaya’an Mendoza told the Asian Journal in a recent interview. “The anniversary of martial law in the Philippines was just a couple weeks ago, so we have come from a place when one dictator took over. History can be replicated again.”

Mendoza — who helped mobilize the Filipino American community following the reignition of the Black Lives Matter movement this past June — described a present-day Filipino American community that is slowly but surely becoming privy to the various ways that bureaucracies and systems of power subjugate communities in America.

“I think people are realizing that when the Black community is under attack, when the LGBTQ community is under attack and when the immigrant community is under attack, that means we are all under attack,” Mendoza remarked.

As previously discussed in the Asian Journal, the “post-racial America” myth paints the now as an unprecedented period of equality across all demographics, conflicting with the grim realities of Black Americans, immigrants and other communities.

For the past several months, Filipino American community leaders, including those in FANHS, have been working to mobilize the nearly four million Filipinos in the U.S. to participate civically, but Filipino American History Month provides an opportunity for Filipino Americans to examine the community’s close relationship with social justice and political activism.

“I think people are recognizing that we all have a place in the movement for social justice, whether it is on the front lines providing medical aid to protestors to being behind a computer screen educating our community,” Mendoza said.

A (very) brief history of Filipino American social justice

Celebrated every October to commemorate the landing of the first Filipinos in America in October of 1587, Filipino American History Month was first designated and recognized nationally in 2009.

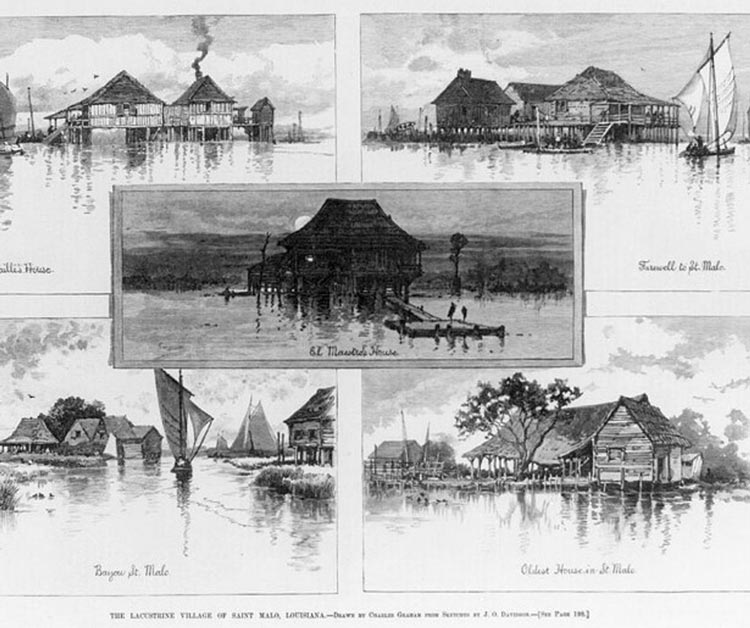

Filipino Americans are the second-largest Asian American group in the U.S, a group that has exponentially grown since the first North American settlement of Filipinos in 1763. These were swaths of Filipinos who were forced into enslavement during the Spanish galleon trade who escaped and established settlements across the Louisiana bayou, eventually dispersing throughout the country.

By the 20th century, the West Coast became the most popular point of settlement (by then, a part of the U.S.), coinciding with a changing of colonial guards when the Philippines became a U.S. territory.

As a pawn for two consecutive colonial powers — Spain and then the U.S. — sovereignty wasn’t just an issue of national political autonomy; it also became about the right to be recognized as a community that has a place in the United States.

Immigration to the U.S. from the Philippines flourished from 1900 to 1934. Filipinos became U.S. nationals when it was realized that Filipino workers could fulfill the demand for cheap labor in agriculture, cannery and domestic servitude.

But Filipino immigrants of the manong generation faced intense racial discrimination prompted by changing immigration policies, anti-miscegenation laws (the prohibition of interracial coupling) and oppressive labor laws that kept wages low and conditions nearly unlivable.

This prompted a wave of workers strikes and demonstrations, most prominently led by fabled Filipino organizer Larry Itliong, the godfather of the labor revolution that put Filipino American activism on the map.

Fast forward to the present when the world is plagued by intense political division, fights for racial justice and, of course, a literal plague when social justice once again comes to the fore of collective consciousness.

The wound of the martial law era in the Philippines remains fresh for stateside Filipinos and their American descendants as a reminder that progress isn’t linear, that tyranny and loss of basic freedom and rights occur in a domino formation.

Especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic that has disproportionately affected front line health care personnel, communities of color and essential workers (which prompted weak government response), the need to participate in meaningful activism has never been more dire.

Moreover, thousands of anti-Asian hate incidents have been reported by Asian Americans across all cultures, prompting the question over whether or not America is truly welcoming of all races and ethnicities, Mendoza noted.

“We’re seen as the perpetual foreigner, so regardless of where this virus came from, this rhetoric will always come back to haunt us. And we should never throw our Chinese brothers and sisters under the bus and be like, ‘We’re not Chinese.’ [Racists] don’t care about that,” Mendoza said.

A more inclusive future

One way that Filipinos can manifest social justice efforts into their daily lives is to become a beacon of information on these pressing topics and to marshal the people in their lives to get involved, whether that’s through phone banking, volunteering for campaigns or even simply voting.

Filipino Americans for Joe Biden — made up of key Filipino Democratic volunteers across the country — is currently making its last-ditch efforts to drum up support for Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, who has been characterized as an antidote to the current administration.

A 2020 Asian American Voter Survey found that Filipinos are the second-largest Asian American group to support President Donald Trump, a leader who has stirred antipathy from Democrats, Republicans and moderates alike for his restrictive social policies and his efforts to scourge basic constitutional rights, as the Asian Journal recently reported.

The admiration many of these Filipino Trump supporters have for the current administration is rooted in a warped view of rugged individualism and American exceptionalism that neglects the basic need for community-centered, inclusive solutions.

According to Mendoza, the key to cultivating a successful social justice force — especially one that stands the test of time and isn’t built upon superficial and performative means of activism — is relationship and community building and finding which social justice avenues are the right ones to follow.

If you’re immunocompromised and can’t attend a protest, you can use the internet and telecommunications to participate in specific movements and causes. Donating to reputable charities or financially supporting those who are able to take their activism to the streets is another way to rally behind a movement. Using your specific talents, whether it be graphic design, writing, videography or any other creative outlet, is another way to participate.

But the strongest impact comes from educating yourself and others, especially family members, about the nuances of issues like police brutality, voter suppression or immigration reform.

Whatever form your chosen mode of activism takes, Mendoza emphasized the potential of the Filipino American community to build a future that is more informed, civically engaged and inclusive of all races, ethnicities, genders and bodies.

“We need to ground ourselves in the legacy that we all hold on this stolen land. When it comes to social justice because we have always been here and a lot of the times we’ve been erased from those stories, so it’s important for us to remember and to uplift all those who have come before and who will come after that fight for social justice for all communities,” Mendoza added.