“Harana, as the song introduces, is an old Philippine tradition of courtship in which a man bears his heart in song to a woman (and sometimes vice versa), while standing underneath her window at night.”

“Harana, as the song introduces, is an old Philippine tradition of courtship in which a man bears his heart in song to a woman (and sometimes vice versa), while standing underneath her window at night.”

WITH Valentine’s Day approaching, we look back at a Filipino tradition that illustrates one’s love in the form of romantic songs.

In 1997, Filipino band Parokya Ni Edgar came out with a song that would become one of the Philippines’ most popular love songs to date.

The song describes a scene in which a young man in old faded jeans, carries roses, and nervously prepares to serenade a lady he likes in the cold and star-lit night, hoping she’d fall in love with his song and him.

The chorus, like the opening lines of the song, asks in Tagalog, “Uso pa ba ang harana?” (“Is harana still in style?”)

While the sound is one reminiscent of 90’s MTV, the song was meant to encapsulate the awkwardness, vulnerability, and even transparency felt by previous generations of Filipinos who wooed significant others through serenades.

Harana, as the song introduces, is an old Philippine tradition of courtship in which a man bears his heart in song to a woman (and sometimes vice versa), while standing underneath her window at night. Its music — unlike the Parokya Ni Edgar song — featured sweet habanera rhythms and impassioned lyrics.

While it’s difficult to pin exactly when harana first began in the Philippines, the practice is believed to have started in the 1800s and was influenced by Spanish folk songs. By the 1930s, it reached its peak across Philippine provinces.

However, the tradition has become nonexistent, remembered only by those who have been fortunate enough to experience or engage in harana, or learn about it growing up.

Critically acclaimed classical guitarist Florante Aguilar was among those who heard about harana while growing up in the Philippines’ Cavite province in the 1970s. This encouraged him to learn more about the music form after being away from the Philippines for 12 years.

“During fiestas, our neighbor’s gardener who was a bandurria player, would get together with his friends and play rondalla and harana music in his shack by the gardens,” recalled Aguilar.

He himself got involved in the local music scene as a child, which gave him even more insight into the Philippines’ unique music scene.

“I was 9 years old and I remember being amazed at how everyone played different instruments — octavina, the laud, double bass, even a banjo,” said Aguilar, whose instrument of choice back then was the octavina, a guitar-shaped Filipino instrument.

“It was only when I got older did I realize what a privilege it was to be part of this circle,” he added, noting that many in the group were in their 60s or 70s. “I felt like I got a pretty good glimpse of history, kind of like a time machine.”

Remembering a dying tradition

Strike up a conversation with any Filipino who experienced harana’s golden age, and they’ll likely light up with stories of how either they wooed their significant other as a haranista, or were wooed themselves.

In the award-winning 2013 documentary “Harana: The Search for the Lost Art of Serenade,” Aguilar met with people who reminisced on the days they met their spouse through harana.

One woman, Liwayway Espino, talked about how she never minded when haranistas would disturb her sleep, and how news of one being serenaded would quickly become the talk of the town the next morning.

“This is the experience I will never forget from my youth,” said Espino.

Aguilar’s most significant encounters during his search for harana were when he met three men considered to be expert haranistas in their communities.

There was Felipe Alonzo from Ilocos Sur, who grew up in the 1930s, learned the guitar himself, and eventually began recording Ilocano haranas for Villar Records.

Then there was Celestino Aniel, born in 1946 in Cavite, who learned songs by artists like Ruben Tagalog and Larry Miranda through the radio. His singing style has been described as being similar to American crooners Perry Como, Nat King Cole, and Bing Crosby.

Also born in 1946 in Cavite was Romeo Bergunio who was a winner of his town’s harana competition. Bergunio learned harana songs — including never before recorded songs — from his father and grandfather.

The three joined Aguilar in performing as the Harana Kings, traveling around the Philippines to reintroduce original harana love songs to Filipinos including to a young man in the historic city of Vigan.

Capturing a real harana on film, the Harana Kings helped the young man named Brian court a classmate of his by performing “O, Ilaw” (“Oh, Radiant Light”) to her and later her parents.

“It was so genuine and Brian was so painfully shy,” said Aguilar. “I think it’s very rare to capture that shyness born out of being in love, and it was really brave of him to let us do the serenading for him,” added Aguilar. “Imagine going under the window with a bunch of old men in tow, he could have been easily laughed off. He was really game and it shows the length he’d go to express himself to the girl.”

‘Not just any love song’

It’s undisputed that Filipinos have and continue to be fans of love songs, and even the dedicating of love songs. This is evident by the songs at the top of Filipino charts today where almost all have to do with expressing strong feelings for another.

However, harana music is not just any love song, explained Aguilar. A traditional harana song itself has very particular characteristics.

A crash course in harana would highlight that truly authentic haranas are marked by a distinctive style or “stamp of authenticity” as Aguilar once wrote. For one, the haranas follow a 2/4 habanera rhythm. This differs from the 3/4 timing of another traditional form of love song, the kundiman.

When it comes to arrangement, haranas begin with a solo guitar introduction, followed by verse one and verse two, another solo guitar in the middle, then back to verse two until the end. Some flexibility allows short exchanges between voice and guitar in the middle of the song.

Another way to distinguish a true harana song is to look at its lyrics.

“A good clue is in the lyrics, which places the singer right in the middle of serenading,” said Aguilar.

Harana lyrics also use pure and archaic Tagalog words no longer used in everyday conversations.

Classic examples of traditional harana songs are Ruben Tagalog’s “Dungawin Mo,” “Hirang” (“Look Out the WIndow, My Love”), and “Kay Lungkot Nitong Hatinggabi” (“How Sorrowful is the Night”) — all of which are accompanied by a guitar or two.

Harana also adheres to a certain process that emphasizes the formality of the practice. The first stage is the Panawagan or announcement that the haranistas are outside the window. This is followed by the Pagtatapat or proposal, which takes place inside the house, and only if the serenaded opens the window and is invited into the house. Following the proposal may something be the Panagutan, or response by the serenaded, and then again by the haranistas. The final stage is the pamaalam, or the farewell.

Modern ‘haranistas’

While the days of true haranistas may exist today only in movie scenes, or reminiscent stories, the practice of serenading loved ones thrives, but in a more modern way — booked online and delivered to loved ones along with flowers, chocolates, and even teddy bears.

In Cebu, a company called Harana.ph has been offering serenading packages to Filipinos for over six years. Watch any of their videos and you’ll see heart-felt reactions of loved ones reveling in the Original Pilipino Music (OPM) songs being sung by talented singers.

“We basically have three packages, including our Premium Package where the singer is a voice coach of one of the most popular TV shows in the Philippines,” said Jane Soco, Harana.ph’s managing director.

Their services have proven to be most popular outside of the Philippines by customers looking to find a unique way to show their appreciation for loved ones back home.

“Eighty-percent of our customers are Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) who are unable to be with their loved ones during special occasions like birthdays, anniversaries, and Valentine’s Day, said Soco.

When it comes to song requests, OPM songs like “Ikaw” by Yeng Constantino are among customer favorites.

Unending love for ballads

While there’s no telling whether harana will find its way back into the hearts of future generations, there’s no question that Filipinos will continue to have a sweet spot for “hugot” inducing songs — songs that tug at the emotions.

“I submit that the Filipinos’ penchant for sad and pensive songs is a manifestation of the primeval kundiman sentiment,” said Aguilar. “It’s a direct result of the national affinity for sad songs dating back to pre-colonial times.”

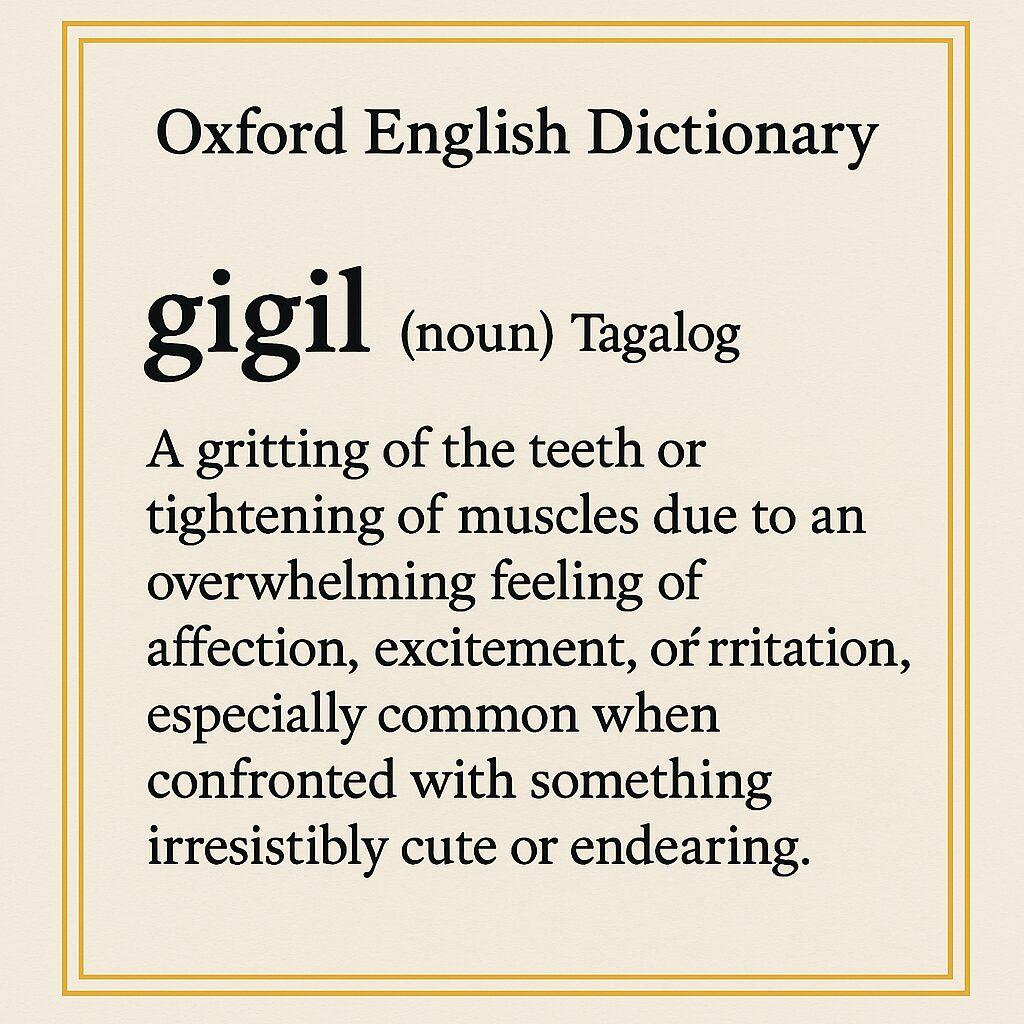

“We believe that music is a language we can all speak and understand,” said Soco. “Since Filipinos are known to be one of the most talented people in the field of music and continuously indulge in enjoyable recollections of past events in our lives, we still get ‘kilig’ whenever we see someone serenading their loved ones.”

“Kilig” is a Filipino term that describes the feeling of romantic excitement.

“Celebrating special occasions in the Philippines will be more fun with a little twist of harana,” added Soco.

And for those interested in learning more about the country’s unique past tradition of harana, Aguilar encourages people to listen to some of the great original harana compositions by artists like Ruben Tagalog.

And of course, there’s the Harana Kings’ album “Introducing the Harana Kings” which features 14 tracks recorded by Aguilar, Alonzo, Aniel, and Bergunio.

hi, great article. i’ve learned so much reading through this. what stuck me the most was this quote right here: “I submit that the Filipinos’ penchant for sad and pensive songs is a manifestation of the primeval kundiman sentiment…It’s a direct result of the national affinity for sad songs dating back to pre-colonial times.” it’s just crazy to realize that our collective past as Filipinos has a direct effect on me today, not only does it influence the type of songs i like, but also shapes my way of thinking.