The renowned best-selling writer talks about her release “Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion” and how the COVID-19 crisis props up capitalist structures

WITH the year more than halfway over, the maelstrom that is the year 2020 continues to impose an unabating state of dread underscored by confusion, anger and despair.

A year that began with the plausible fear of nuclear war with Iran to the awareness of a new mystery virus that catapulted a full-blown pandemic that has, unless you’re a penguin in Antarctica, turned the world upside down. With more than 150,000 people dead (and counting) from COVID-19 and the further politicization of the virus, which by its nature is apolitical, doesn’t show much hope for the future.

Civil unrest continues to ravage the United States following the re-emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement that has Americans across the country reconfiguring the ways in which systems and institutions slight people of color, especially Black Americans.

And, all of this is occurring in a generation obsessed with personal branding, a culture that espouses a very narrow view of wellness and success through algorithms and optimization: the corporatization of self-care, the transparent way that capitalism has monetized “being yourself,” and an attention economy that pushes a toxic image of productivity.

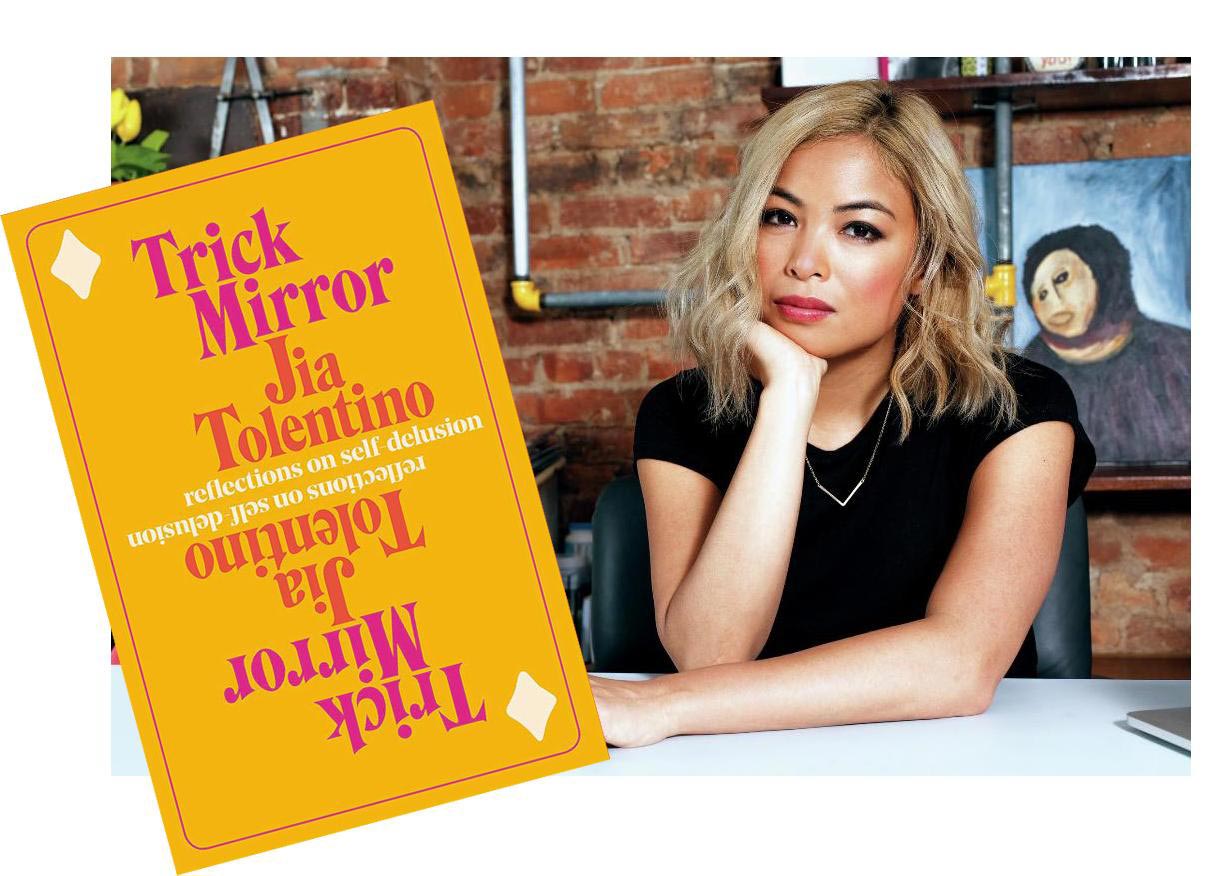

These topics form the foundation of the popular New York Times bestseller, “Trick Mirror: Reflections of Self-Delusion,’’ by celebrated Filipina American writer and journalist Jia Tolentino of The New Yorker magazine, who last week embarked on a second book tour to celebrate the release of the paperback version of her debut book.

A voice of a generation, Tolentino’s book navigates and tries to make sense of the ways that systems of power exploit people’s insecurities — or, in more nefarious cases, procure such insecurities. And, to be a millennial or a Gen Z-er in 2020 is to be a case study of a digitized world that seeks to prop up more and more funhouse mirrors that further distort the self into oblivion.

And during a global pandemic that has people depressed, angry, confused and frustrated while quarantining in their homes, it is perhaps the most opportune moment for this distortion to reach unprecedented levels of influence.

“One of the things that is really important for people that were sort of raised on the internet, whose industries are being shaped by the internet and people who could use the internet para-professionally is separating the internet’s incentives from your own,” Tolentino explains in a virtual interview with Rabbi Aaron Potek of the Washington, D.C. synagogue Sixth & I on Monday, July 20.

“Trick Mirror,” which was released in August 2019, comprises nine sweeping essays that intertwine relevant critique of these deeply rooted cultural issues (and the ways they con people into delusion) and Tolentino’s personal life and her upbringing as the daughter of Filipino immigrants in Houston, Texas.

The densely-packed book remains a modern Bible, a thought-provoking salve to the confusion many felt after the 2016 election for an entire generation that grew up in a world rocked by war, financial crises and surveillance capitalism.

But the point was never to categorically answer questions because, as Tolentino points out, that’s almost impossible. Particularly, the point isn’t to denigrate the emergence of the internet and social media. The first chapter of “Trick Mirror,” called “The I in Internet,” is a sweeping critique of how the modern computer became a vehicle for nefarious business practices and for people to present a particular brand of themselves.

The internet’s incentives, Tolentino says, are “to make us feel as if it’s normal to self-broadcast to an audience that is hypothetically increasing indefinitely until the end of time” and that the top most influential properties on the internet “want us to use it compulsively and wants us to feel superior to other people and wants us inferior enough that we get more addicted that way.”

Tolentino points out that in her writing and reporting of the internet, “I have tended towards the critique because the utility side is so obvious.”

She continues, “It’s magic and really parts of it are incredibly wonderful and especially now during the protests, the whole world is changed because of the way that videos of police brutality were all over the internet and completely unavoidable in a way that has really changed the conversation and the whole discourse around policing and racism in a way that’s really incredible.”

In-community discourse on racism, many of which wouldn’t have occurred without the internet, Tolentino says, is also one of the things that have sparked from the protests and the movements for police abolition. Anti-Blackness within the Asian American community, on which the Asian Journal has previously reported, is pervasive and relevant to nearly every Asian community in the United States.

Understanding what it means to be Asian American, however, is the first step to unpacking the community’s (and the specific cultures that exist within that broad term), tenuous race relations, especially with the Black community.

“One of the most salient parts of being Asian American is that knowing you’re kind of an invented group identity and, for me, learning that I could benefit from the same systems that were punishing me at the same time,” Tolentino says, pointing out the radical origins of the term “Asian American,” which was first documented in 1968 by a coalition of Asian American college as a response to the labor strikes and civil rights battles of that time.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made it more difficult to engage within the community in a meaningful way, but understanding the origins of Asian American solidarity movements and the history of Asians in the United States is a start, Tolentino says.

Many Asian Americans today are grappling with the desire to stand in solidarity with Black Americans who are calling for systemic change while also fighting for their own respects in a time when anti-Asian sentiments are also rampant due to the false association between the COVID-19 virus and the Asian community.

As Tolentino writes in her book, social media has perfected the ways it encourages people into adopting hasty, fallacious ways of thinking, that more than one thing can be true at once: Black Americans are being slighted in ways that the Asian community is not, and the Asian community is also facing its respective slights, Tolentino shares.

“I find a lot of grounding in just the actual history of how you know this term of Asian American was meant to be a radical term and it still can be, especially for young people,” Tolentino offers. “It feels like that this is a weird position on the bullshit racial hierarchy of the United States where you have an advantage that you can use on other people’s behalf, but it doesn’t mean you have to ignore whatever you face in your own life.”

“There’s such a long tradition of Asian solidarity within the civil rights movement that now it’s the time for our own version of that,” she remarks.