IN the inclusive rider era of Hollywood, it’s almost become a pedestrian party line to pledge support for diversity but the actual outturns thus far of that proclamation still leaves more to the imagination.

But the world of animation — a space governed by entertainment bigwigs, Disney, Pixar and Dreamworks — is a space where anything goes, and the effort to diversify is evidently much easier when characters can be drawn whichever way, new fantastic worlds can be rendered from pure imagination and voice talents don’t typically have to contend with the marketability factor in casting.

Little do many of us know that behind such cherished films like “Zootopia” and “Wreck-It Ralph” and TV shows like the cultural behemoth “Avatar: The Last Airbender” are Filipino American animators who have established fruitful careers as animators, storyboard artists and, most recently, directors.

Rise Up Animation, an initiative created by people of color in the animation industry, was co-founded by Fil-Am animator Bobby Pontillas, whose credits include contemporary Disney classics such as “Wreck-It Ralph” and “Big Hero 6.”

The initiative’s objective is, simply put, to buoy up aspiring animators of color and uncover their potential. In the year of COVID-19, the Rise Up Animation’s offerings of programs and workshops are, like most things these days, limited. But the organization — which has partnered up with various Disney properties — has been hosting talks with some of the biggest veteran animators in the game.

Among those animators include Filipino American talents such as Pontillas, Josie Trinidad, John Aquino, Ian Abando and Bobby Rubio, all of whom have worked on an entire generation’s worth of nostalgia and developed enough career longevity to become formidable forces in the push for Filipino visibility and recognition in animation.

“It’s quite an honor to be in the presence of directors and Filipino artists whom I admire and look up to and it’s great that we are in this time and space where our work is being recognized,” Pontillas said in a special “Filipinx Directors in Animation” panel with Trinidad, Abando, Rubio and Aquino on Thursday, Aug. 6.

Since its inception, Disney set the blueprint for animation, and like other kids, Aquino acknowledged Disney’s role in fueling his early interest in drawing. But Aquino — like Rubio and Abando — was more influenced by comic books, particularly those of Will “Whilce” Portacio, who created works on popular superheroes like the X-Men, The Punisher, Iron Man and Spawn, to name a few.

Like the other artists on the panel, Aquino knew early on that he would lead a life in illustration, a dream that led him to Walt Disney Animation Studios. As a crucial figure in its visual effects and animation departments, Aquino has worked as a modeler for some of the biggest hits to come out of Disney and Pixar of the last decade: “Tangled,” “Wreck-It Ralph,” “Frozen” and “Frozen 2,” “Big Hero 6” and “Moana.”

Though he’s celebrated major achievements in his professional life, Aquino acknowledges his mother as a key motivator that has gotten him to the point he is now. His mother, who contrasted the Dragon Lady stereotype of Asian mothers, championed the artist’s dreams.

“She encouraged me to do whatever brought me joy and she always supported me, and I think that kind of [parental] support goes a long way for Filipinos who want to pursue careers in the arts,” Aquino shared.

For these artists, the shared goal of establishing a cultural foundation for Filipino animators may be an uphill journey, but it’s a battle that they don’t plan to quit. And that tenacity, coupled with the inherent desire to share personal stories through animation, is what prompted a crucial milestone in 2019.

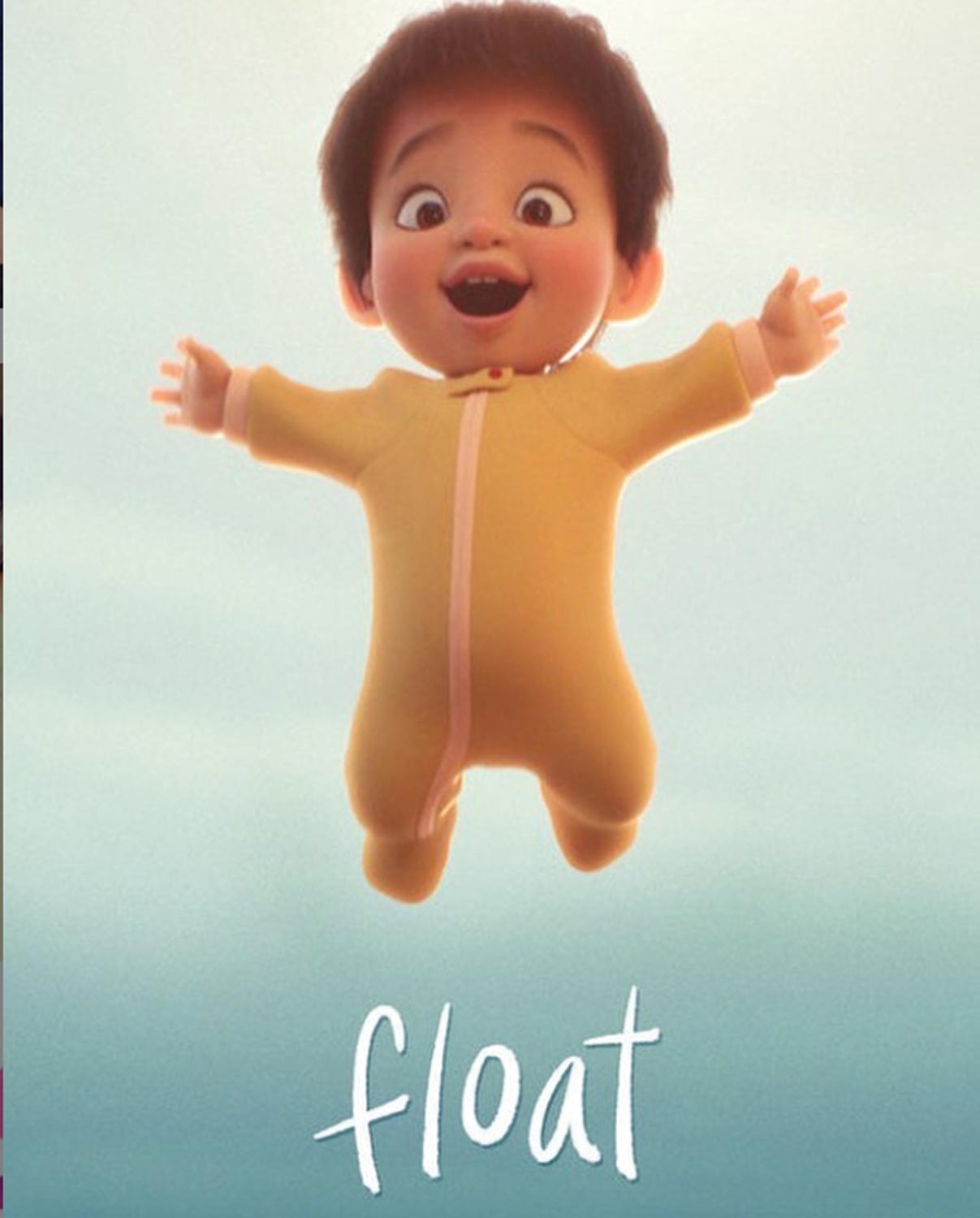

“Float,” Rubio’s directorial debut about a Filipino father with a son who can float in the air that was released on Disney+ in November, was the first-ever animated short featuring CGI Filipino characters.

With a running time of only seven minutes, “Float” beautifully tells a heart-warming story that was inspired by his own experience as a father with a son on the autism spectrum. In the story, the father struggles with showing his son’s special abilities to the world, afraid that the son will be subject to ostracization. Eventually, the father realizes that the son’s unusual ability is not a hindrance, but a gift.

A gift, too, is the short film’s expansive relatability and universality, said Rubio, who also worked as a story artist on Disney and Pixar’s “Inside Out” and “Monsters University” as well as the wildly popular Nickelodeon series “Avatar: The Last Airbender.”

After two decades of working on various Disney projects (Rubio’s first animation credit was on the 1995 film “Pocahontas”), Rubio began storyboarding “Float,” which was directly inspired by his son’s autism diagnosis in 2010.

| Photo courtesy of Pixar

“The floating was a metaphor for me. It was supposed to be a story about autism, but then I saw that it could mean other things and could represent any kind of difference like gender difference, racial difference,” he noted. “I also heard Filipinos suggest that they thought it was a metaphor for assimilation, that the boy was trying to embrace his Filipino heritage but the dad was, like, ‘No, you’re American,’ and tried to stifle his Filipinoness.”

Rubio added, “That’s important because it’s like, I don’t have to assimilate and I could accept and embrace my culture. [When I heard this interpretation from Filipinos] I felt so grateful that my story could be seen that way, and I’m so thankful for all the love and support that the film has gotten.”

If “Float” is the foundational genesis of emerging Filipino stories in the mainstream, then the future is boundless, which Rubio’s fellow Disney animator Trinidad acknowledges.

Trinidad, a second-generation Filipino American, grew up in Oxnard, California and, like Aquino, had parents who were “very supportive of the arts.” The moment that she knew animation was in her future was an early viewing of Disney’s “Robin Hood” when she was a young child and realized that cartoons were drawings that were created frame by frame.

What followed was her entrance into CalArts and employment at Disney in the early aughts when animation went from a strictly 2D medium to one that now employs CGI and other technological advances.

At Disney, Trinidad wears many hats, providing voices in various Disney and Pixar films to working as a story artist on award-winning films like “The Princess and the Frog,” “Tangled,” “Zootopia” and the “Wreck-It Ralph” films. But, now more than ever, Trinidad feels emboldened to share Filipino narratives through her art.

“I want to show that it’s beautiful and very, very unique and complex and that it’s not a monolith,” Trinidad remarked.

For her work as a story artist on the 2016 hit “Zootopia,” Disney sent Trinidad to the Philippines to gather inspiration for the film, which would later win the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. While in the Philippines, she visited De La Salle-College of Saint Benilde and the animation studio Toon City in Mandaluyong.

“I’ve just been floored by the Philippines. There’s so much talent there and so many different storytellers and filmmakers that I have just been so impressed by and that makes me very, very proud,” Trinidad shared, punctuating the reservoir of talent and artistry within the global Filipino community.

The artists who shared their enthusiasm for diverse story-telling on Thursday emanated excitement over the future of animation, even taking asides to brainstorm Filipino-centric stories they could tell.

But the reality is that, even though an animation department and writers’ room could be diverse, nothing will happen unless power dynamics change within studios like Pixar and Dreamworks and, especially, in the corporations that own them like Disney and NBCUniversal.

Abando, who is a story and storyboard artist at Dreamworks (and has worked with Laika Studios), pointed out that studios are often guided by profits and marketability over cultural impact and narrative innovation. This, he remarked, is what leads to sequels of sequels and reboots (and then reboots of those reboots).

“Studios are always trying to look for the next thing to kind of riff from, the next thing that [they can foresee] will be successful,” said Abando, whose credits include “Despicable Me 2,” “The Emoji Movie” and “Trolls.”

“It’s like, you have all this room and you buy all these properties that are about people that aren’t like you, but why aren’t any of those people on your team? Why do you strip away all those things that you think scare your audience away?” he pondered, noting that pushing projects based on the premise that they showcase diverse talent and storytelling should be “enough” for studio executives to greenlight those projects.

But, at the same time, Abando rejects quotas and tokenism in Hollywood, or the notion of shallowly telling diverse stories without the intention of taking those projects seriously as forms of art. In other words, studios should recognize that both ideas — that Filipino animators should be uplifted and their art should be valued as universally-relevant stories — are simultaneously true.

“I appreciate people like you, Bobby [Rubio], who can be 100% true and not be afraid of being rejected because people want to be as personal as possible and be seen, and I think that lack of precedent in [the animated] industry isn’t understood,” Abando said, adding that he hopes that animation will be valued more as an art form rather than just juvenile, escapist entertainment.

He added, “People are like, ‘Oh, it’s just animation,’ but to us, this is our culture as much as being Filipino is our culture. I take animation culture very seriously and I hope to see it elevated to being appreciated as a film and real art form.”