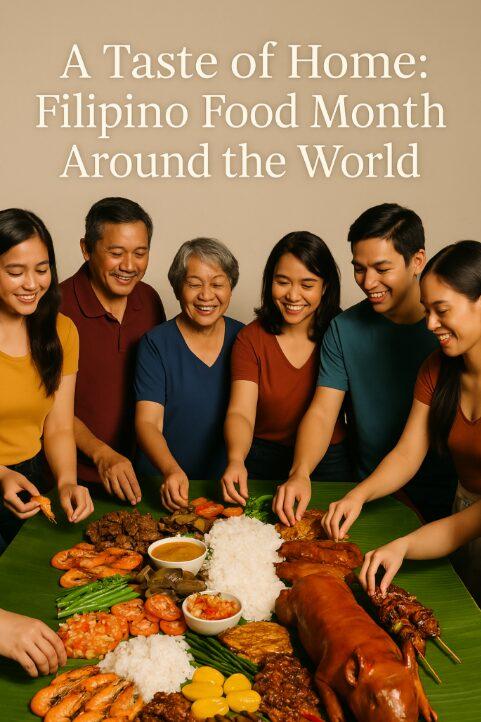

AS the summer comes to an end and temperatures begin dropping (climate change notwithstanding), it’s time to eke out summertime favorites, of which Filipinos, like Heart Evangelista, are all too familiar.

On Aug. 21, the Filipina actor and socialite posted a photo of the summer staple halo-halo, but it wasn’t just regular halo-halo: it was a gold flake encrusted, posh take on the classic icy treat, served specially for a close-knit group of friends.

Served at a dinner party in Los Angeles last month, the dish was the Rolls Royce of halo-halo. It was a creation from award-winning Filipino American pastry chef Sally Camacho Mueller who made the custom-made dish for the party’s co-host, Dion Ugbebor, chief executive of LA-based home care agency Intra Care.

“Halo-halo is just an amazing end to a meal because it’s very simple but really refreshing with the ice and mixed flavors, whether it’s the tapioca buko pandan, which is what I used, or gulaman (gelatin),” Camacho — a private chef and pastry consultant in Los Angeles — told the Asian Journal in a Zoom interview on Tuesday, Sept. 7.

What makes Camacho’s glitzy halo-halo perfectly fit for an upper-echelon crowd is not just the gold flakes that effortlessly varnish the dish, but the neat presentation and understated elegance of the dish, which is typically more slap-dash in preparation and flamboyant in color.

Halo-halo — which is literally “mix-mix” in Tagalog — comes from Japanese cuisine, specifically the kakigori (shaved ice) category of desserts.

The beta version of the beloved dessert consisted of boiled monggo (mung beans) cooked in syrup and served atop crushed ice and milk, but over time, more native Philippine ingredients — coconut sport, jackfruit, ube, plantains, ice cream, leche flan and pinipig (toasted rice) — were added to create a colorful concoction that is highly versatile to accommodate a wide range of palates, diets, and, of course, budgets.

“What resonates with me is thinking about the ways our moms and aunties cooked at home,” Camacho said of her approach to Filipino cuisine. Her special halo-halo was vegan-friendly and included ube ice cream that she made herself, coconut and cashew milk, nata de coco, azuki beans and, of course, the gold flakes.

Even among deep-pocket members of the international Asian community, Camacho’s blingy halo-halo was the star of the modest, yet luxe get-together. Evangelista — who is the daughter of a Chinese-Filipino restaurant tycoon, an heiress to a sugarcane plantation and cultural tastemaker in her own right — is just one of the many prominent guests at this dinner.

The charismatic co-star of Netflix’s “Bling Empire” and entrepreneur Kane Lim, who is close friends with Camacho, Ugbebor and Evangelista, was also present at the dinner that brought together its own mix of Asian cultures and backgrounds.

“[The halo-halo] kind of reminded me of a globe, like a blingy form of the earth,” Lim told the Asian Journal.

And Lim’s take on Camacho’s halo-halo isn’t far off from what the world actually looks like through the lens of his many mainstream cohorts.

Since the 2018 film adaptation of Kevin Kwan’s “Crazy Rich Asians,” representations and depictions of unbelievably wealthy Asians and individuals of Asian descent have become more in-demand, showcasing the opulence of old and new money through reality shows like “Bling Empire,” “Singapore Social” and “The Fabulous Lives of Bollywood Wives.”

What separates these real-life crazy rich Asians from other one-percenters is that there isn’t a sense of passivity or careless swaddling of wealth. Lim, 33, is the son of an oil tycoon who raised him to be self-reliant.

In an interview with Voyage LA, Lim said that advice, and a “small loan” from his father, allowed him to invest in stocks and to found Kix Capital, an international holding company that says it has “investments in real estate, biomedicine and renewable energy.”

But what Lim is perhaps most known for is his personal investment in fashion, a move that he parlayed into becoming a luxury influencer. A quick scroll down Lim’s Instagram page yields a lush lookbook of Alexander McQueen, DSQUARED, Christian Louboutin, Hermes and other names that belong on Rodeo Drive.

Similarly, the contemporary Filipino food scene in LA is part of the “boba liberalism” rubric, a larger strain of Asian American elitism that engages in trendy liberal sociopolitics but merely results in superficial, passive solidarity.

The inundated images of Asian wealth and luxury do appeal to the broader call to Asian representation in mainstream media, but it is impossible to ignore the other side of the Asian American experience in 2021.

Fashion and food are efficient ports of entry to Asian culture, but what are the effects of those ports being overtaken by the richest of the rich? How does the notion that all Asians are “well-off” ultimately affect the vast communities of Asians who are not?

The unfathomable wealth displayed through the onslaught of content featuring jet-setting, haute-couture-donning reality stars — as well as the model minority myth — belies the reality of a vast majority of Asians, particularly of Asians who live in the United States.

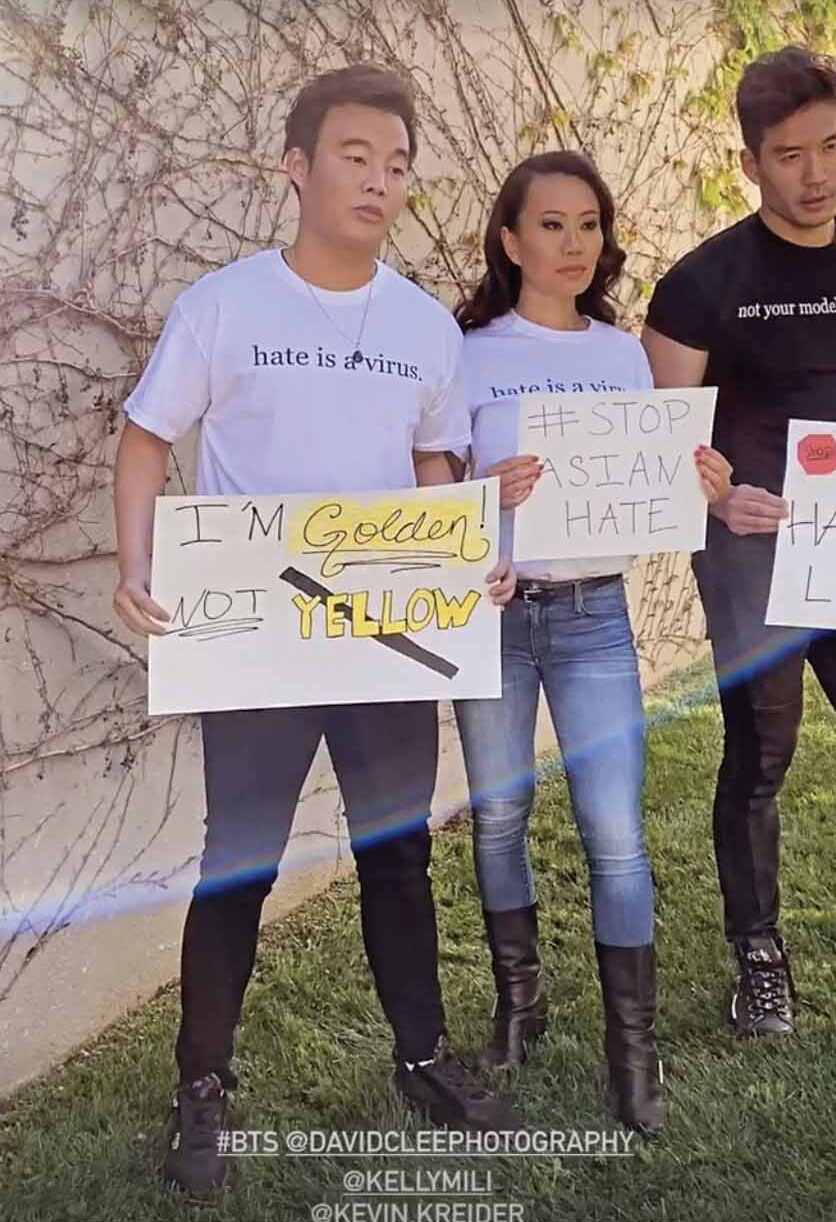

At a time when the country is reckoning with its history (and present) of discrimination toward the Asian American community, finally acknowledging and advocating for the invisible masses of the community has never been more urgent.

Income inequality has risen overall since the 1970s, but that wealth gap is greatest among Asian Americans, according to a 2018 report from the Pew Research Center, which analyzed available government data.

The standard of living for Asians at the top 1% of the economic ladder skyrocketed over the past 50 years as Asian Americans went “from being the most equal to being the most unequal among America’s major racial and ethnic groups,” a trend coinciding with the vast displays of luxury propagated by things like media representations of insanely affluent Asians, gold-encrusted desserts and the persistence of the model minority myth.

The income of Asian Americans at the 90th percentile doubled from 1970 to 2016; middle-class Asian Americans saw a 54% increase in income while Asians at the 10th percentile increased by only 11% over the same time period.

The surges of Asian immigration in the latter half of the 20th century brought an overwhelming diversity of cultures, religions, languages and circumstances. In addition to family reunification programs, refugees from Cambodia, Vietnam and other oppressive regimes came to the U.S. in droves with little to nothing to their names.

Now, Asians have the widest wealth gap among other racial groups as of 2018 — and the data has yet to be collected from Asian Americans and Asian immigrants affected by the pandemic and the dramatic increase of anti-Asian hate crimes.

To date, more than 9,000 reports of anti-Asian harassment, assault and discrimination by Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) have been recorded to the Stop AAPI Hate tracker since the beginning of the pandemic, a movement that expedited the long-ignored concerns of the wider Asian American community.

“I think we as a culture in past generations, we don’t really speak up and I think it’s time to speak up,” said Lim, who, over the past year and a half of pandemic, has used his platform to support health care workers and campaign for the Stop AAPI Hate movement.

Lim, who shared that his grandparents were poor migrants from China who came to Singapore “with nothing,” admitted that the wealth divide among Asian Americans was a blind spot in his work but that he feels motivated to use his platform for inclusivity among Asian Americans of all income levels.

“This is when I need to remind myself on how we can help [our community] more, like I just talked to my developers the other day and I’m like, ‘Hey, what about Asian communities? How can we include them more in our projects?’” Lim said.

“I think this is a new era when people are standing and saying, ‘No, that’s enough.’ It’s time to stop and talk about it and let’s approach this and find solutions,” Lim added.

When it comes to unifying the Asian American culinary community, Camacho shared that among Filipino cooks, chefs and restaurateurs, there’s an active understanding of their place in the rich history of Filipino cuisine.

“I think we all know the struggles and what our food has been through and what it can be and what we’re all trying to do,” Camacho said of the “brotherhood and sisterhood” of Filipino chefs. “From my experiences, I believe that everyone is trying to lift each other up and help each other the best we can whether it’s through collaborations to promoting each other.”

And one of the ways that the community of chefs and restaurateurs has been collaborating is through dinner parties like the one that Ugbebor hosted in 2020.

“Everything I do with my culinary talent is always from the heart, it’s always from passion,” shared Camacho, who also partnered with other LA bakers for a Stop Asian Hate fundraiser in April. “I’m so blessed for individuals like Dion and Kane and to be on this platform of making a dinner like this; it’s these relationships that really help raise awareness for our communities and remind us that we need to use our talents to give back.”