COOKIE Hiponia Everman took to heart what Toni Morrison once said: “If there’s a book you want to read, and it hasn’t yet been written, then you must write it.”

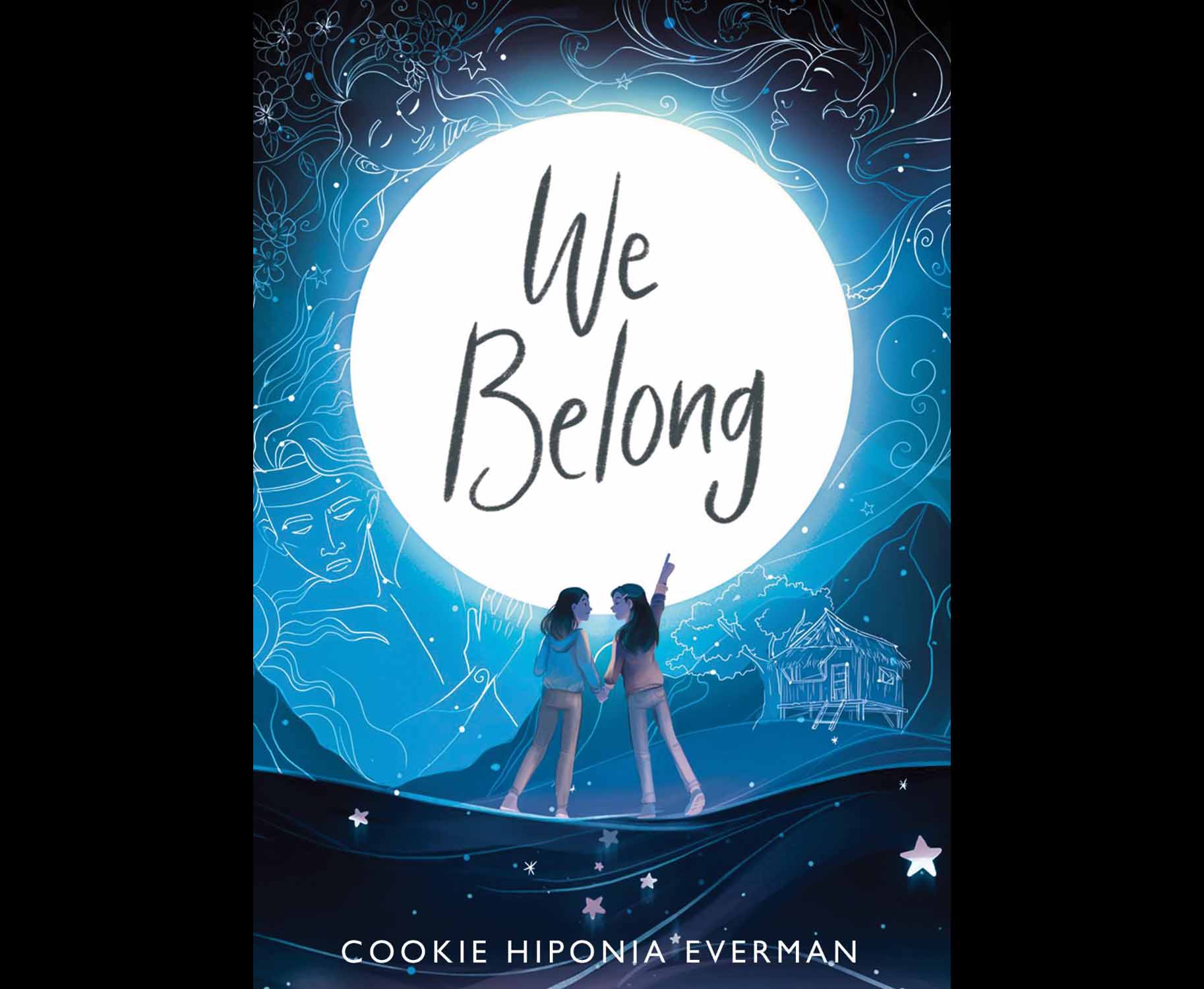

That book is now out and it is called “We Belong,” Everman’s debut novel which delves into and reflects her family’s experiences. Her story ties together Tagalog mythology and tidbits of Filipino culture and history, aiming to fill a gap in children’s literature about the Philippines.

In her past life, she was a video game editor and managed an editorial team to ship back-to-back video game titles on tight deadlines. She is now her own boss and a full-time writer whose poems have been published in several literary journals.

“It’s been surreal,” Everman told the Asian Journal. “I’ve learned to rely on little rituals like my morning coffee and breakfast, afternoon naps, snuggles with my kids to talk about their days, and a pseudo-bedtime for myself where I lie in bed and end up scrolling the internet for a couple hours.”

Everman, who was born in the Philippines and immigrated to America when she was nine years old, wrote her book for herself and her kids, and for all the kids like her who never saw themselves in books. She lives near Seattle with her two daughters.

A self-confessed giant book nerd, Everman and her daughters were at the library a lot and she would always look for Filipino or Tagalog books for them. They found many books that are now family favorites like “Cora Cooks Pancit” by Dorina Lazo Gilmore, but there were no books that spoke to their experiences as hapa kids.

“A lot of the immigrant stories I had read that were written for kids focused so much on the suffering and the trauma of a refugee story or an undocumented migrant story, and while those stories are valid and deserve to be told, the stories of highly educated immigrants who may be doctors or executives in their homelands leave those careers only to become McDonald’s cashiers or Uber drivers in America, working three to five jobs at a time just to survive, also deserves to be told,” she shared.

And that is exactly what she set out to do.

During the first year of drafting the book, she was still working as a videogame editor full-time and raising her two daughters. She wrote chapters of the book on the bus, on coffee breaks, at lunch, during boring meetings, on the back of grocery store receipts while waiting in the parent pickup line after school, on the margins of her hula notebook next to drawings of hand gestures.

It took her about two years from the time she wrote the outline to the time she turned in the manuscript to her editor. She bought herself a bottle of expensive Scotch to celebrate when she turned it in.

Timely title

Saying that she is actually “really bad at titles,” she admitted to stealing them from songs.

“I stole the title ‘We Belong’ from the Pat Benatar song, but I think the first lines of the chorus speak to the themes of the book: ‘‘We belong to the light, we belong to the thunder / We belong to the sound of the words, we’ve both fallen under,” she explained. “As immigrants to this country, we all struggle to belong to it, in whatever fashion. To me, the words ‘we belong’ mean that we belong wherever that light hits, wherever there is thunder, wherever the sound of spoken word moves us. Nobody can tell us where we belong, only we can do that.”

The title resonated more to her and evoked emotions when she realized the cases of anti-Asian hate in various cities across the United States earlier this year continued to grow.

It hit close to home when she saw the case of Vilma Kari, the 65-year-old Filipina who was attacked and kicked in New York with her attacker screaming at her: “You don’t belong here!”

“It made me feel sick to my stomach to think that a Pilipina elder, someone who looks like my mom, was so viciously attacked. It stirs thoughts of violence in my bruised heart,” she shared. “It’s funny; people have also asked me if I knew that my book would come out during a time when anti-Asian hate crimes are on the rise and Asian American and Pacific Islander folks on the diaspora are desperate for people to recognize their humanity and not kill them.”

Everman said that maybe the real question we should be asking is: why is it that a book I mostly finished writing two years ago, part of which takes place almost 40 years ago, reads like it was written two weeks ago and took place yesterday?

“Asian Pacific Americans built this country; we belong here just as much as everyone else does. We’ve certainly earned our place, and continue to earn it with blood, sweat, and tears,” she added.

Everman has come to terms with the fact that she released a debut book in the middle of a global pandemic, which means a book tour is definitely out of the question, which also means that she has to hustle harder to promote it.

“It’s nothing like I imagined it to be. In some ways, it’s been way better than anything I could’ve dreamed,” she said. “The biggest learning is that writing the book is only the very first step. Writing a book is the fun part; the real work is in promoting and essentially hand-selling it so I can make sure I can keep writing more books.”

In the weeks after the book’s release, she drove around the Seattle Metro area and suburbs to sign books at independent bookstores and donate books to Little Free Libraries and the Filipino Community of Seattle’s Community Center.

She is also busy writing another middle-grade book, not told all in free verse but told in text messages and journal entries, which is the vernacular of the 12-year-olds she knows.

“It also has a Pilipino American protagonist and weaves Pilipino mythology and a touch of poetry in the telling because I can’t help it, but also because it’s the best way I could think of to tell the story I’m telling,” she shared.

Memories of PH

Everman was nine years old when she moved from the Philippines to the United States. The last time she visited the country was in 2001, when her family took her oldest niece there for the first time.

Her fondest memories of growing up in the Philippines made it to the book, from catching frogs in the creek at Ayala Alabang Village, to playing with her barkada and cousins, to taking nightly walks with her dad Cesar or her Lolo Andring in Makati City.

“I also have fond memories of standing at the front gate with my Kuya to wait for the taho man. We had our own cups and a full 8 oz cup cost one piso. My brother once tried to get the taho man to fill a bigger cup, and the taho man did, but then he was all, ‘‘Dal’wang piso yan, boss,” she reminisced.

The narrator in “We Belong” is Elsie, named after Everman’s favorite auntie. Tita Elsie is the elder sister of her mom Florecita.

Through this book, she hopes to be able to share not only to her children but to the world as well, the monumental sacrifice her parents made to leave everything they knew and everyone they loved to give their children a better life than they had.

“The most important lesson my parents taught me was that I had to believe in my dreams and work hard to achieve them, no matter what anyone else says,” she pointed out.

With her debut book, Everman has achieved one of her dreams, and along with it, a compelling and all-too-rare story about an immigrant parent sharing her journey and childhood with her children.

Correction: A previous version of this article had a factual error about Everman’s family. We apologize for the error.