WHEN Rose Cuison-Villazor was announced as the Co-Dean of Rutgers Law School in Newark early this summer, she became the first Asian American woman Dean at Rutgers Law School and the first Filipina American Dean of a U.S. law school.

“I’m proud, and I’m grateful for this, for the chance to lead, and I would not be where I am today without the help of many other mentors and friends who supported me along the way,” Villazor told the Asian Journal. “I’m extremely grateful to be in this position and excited to continue leading despite the challenges of the pandemic. This is a position that I hold dear to my heart, and I look forward to continuing to do.”

An expert in immigration and citizenship law, Villazor has served as the Vice Dean of Rutgers Law School in Newark since July 2019. She also is the founding Director of the Center for Immigration Law, Policy and Justice.

Rutgers-Newark Chancellor Nancy Cantor said that as vice dean, Villazor “proved herself to be a remarkably quick study and exceptionally talented organizational leader, mastering the breadth and depth of administrative responsibilities while remaining an extraordinarily productive scholar, teacher, and mentor.”

“She is perfectly positioned to carry forward the law school’s legacy of providing an excellent and inclusive academic environment that is rooted in social justice,” Cantor added.

A nationally-regarded legal scholar with an active record in social justice issues and the areas of immigration, citizenship, property law, and race and the law, Villazor has published in top legal journals including the California Law Review, Columbia Law Review, Michigan Law Review, and NYU Law Review, among others.

She is the founder of the Rutgers Center for Immigration Law, Policy and Justice and a frequent public speaker who has appeared on CNN and has offered commentary for several news outlets, including the New York Times, Washington Post, NPR, LA Times, and The Atlantic.

“It’s an opportunity to be a leader. This time of major challenges also presents opportunities to shape the law school, towards a vision of inclusivity and being welcoming to many different groups of people who don’t have access to legal education,” she explained.

She wants to leave with a vision of being inclusive and creating a pipeline to law school so that more people who didn’t have access to law school before could become lawyers and represent immigrants, marginalized individuals, or work in big law firms and become judges or politicians.

“So my role as a dean, for me personally is an opportunity to be visible and to show other people who look like me that they can also be in this position, and have a seat at the table to make some changes,” she added.

Nurturing her dream

“I must have been a senior in high school when there was a career day. And on this career day, there was a woman lawyer who came and I thought, ‘Oh, maybe I could be a lawyer,'” she recalled. “My parents are immigrants, and they had like many immigrants had experienced racism and exploitation in the workplace. So I knew that that was wrong, and I felt that maybe becoming a lawyer is the path I should take.”

When she went to college, Villazor studied political science and from there, she began thinking that law could be a path for her. She ended up going to law school at American University in Washington, DC and eventually became the first lawyer on both sides of the family.

She practiced law for four years in New York City, and as a civil rights lawyer, she represented immigrants who were experiencing discrimination in healthcare and access to hospitals to clinics because they didn’t speak English well, or because they’re undocumented.

Villazor then got a fellowship to work at Columbia Law School and that is where she made the transition to academia, From 2004 to 2006, she was researched and wrote about immigration law and human rights.

She became a law professor and her first teaching appointment was at Southern Methodist University School of Law in Dallas, Texas before moving to Hofstra Law School in Long Island. After three years, she moved to the University of California at Davis and stayed there for seven years.

In 2018, she joined Rutgers Law School and was appointed the Vice Dean in 2019. Last July 1, she officially became Co-Dean.

With her position as dean, Villazor hopes to be an inspiration to others.

She also wants to encourage more Filipinos, more Filipino Americans to go to law school and consider becoming law professors and becoming law school deans, administrators after graduation. According to her, it is important to go to law school, even if you don’t want to become a lawyer because it’s a study that helps you to be a critical thinker.

“It allows you the opportunity to eventually represent people who need your help with their liberty rights, with their houses, businesses and so it’s a great opportunity. It’s a great job and a career that that many Filipinos to this day are not really as invested in unlike, let’s say the medical fields,” she explained.

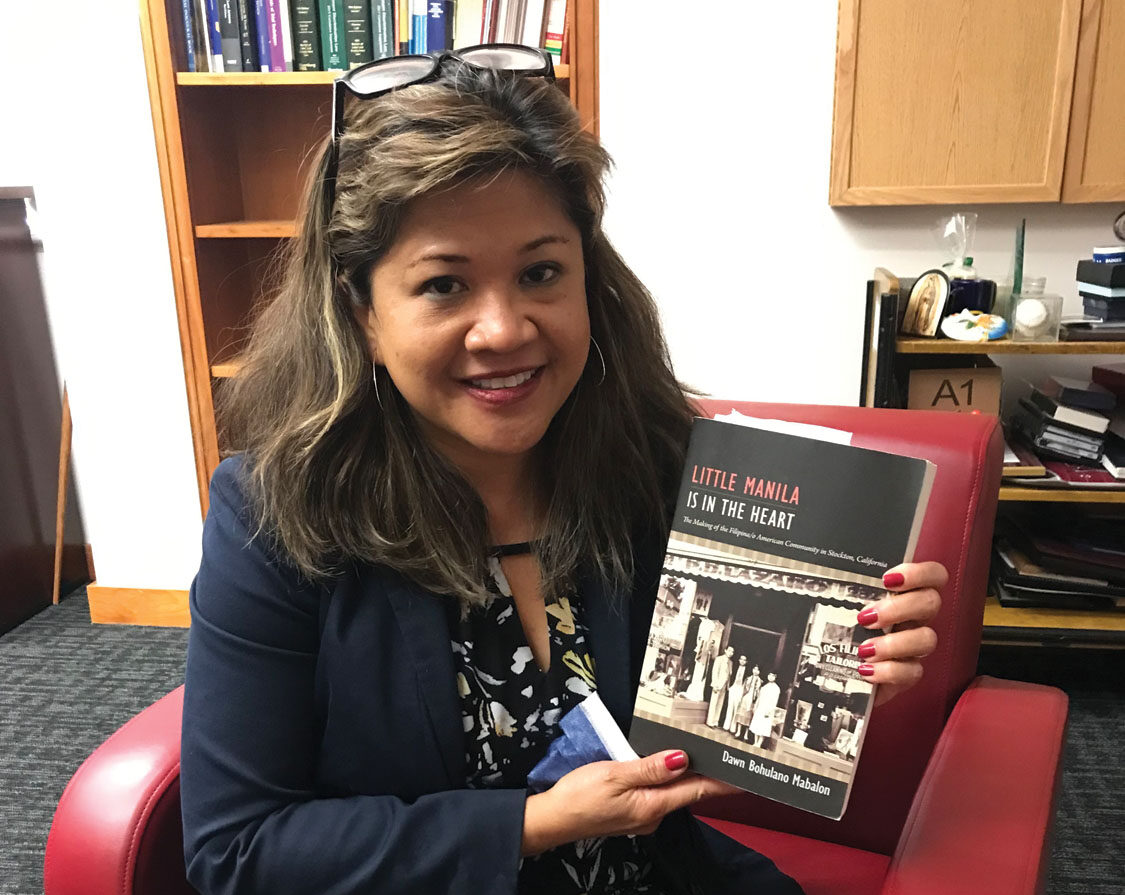

Co-editor of two books, The 1965 Immigration Act: Legislating a New America (with Jack Chin) and Loving v. Virginia in a “Post-Racial World”: Rethinking Race, Sex, and Marriage (with Kevin Maillard) published by Cambridge University Press, Villazor is also co-author of leading casebooks on immigration, race and property law.

She has testified before Congress and the California and New Jersey state legislatures. In 2011, she received the Association of American Law School’s Derrick Bell Award.

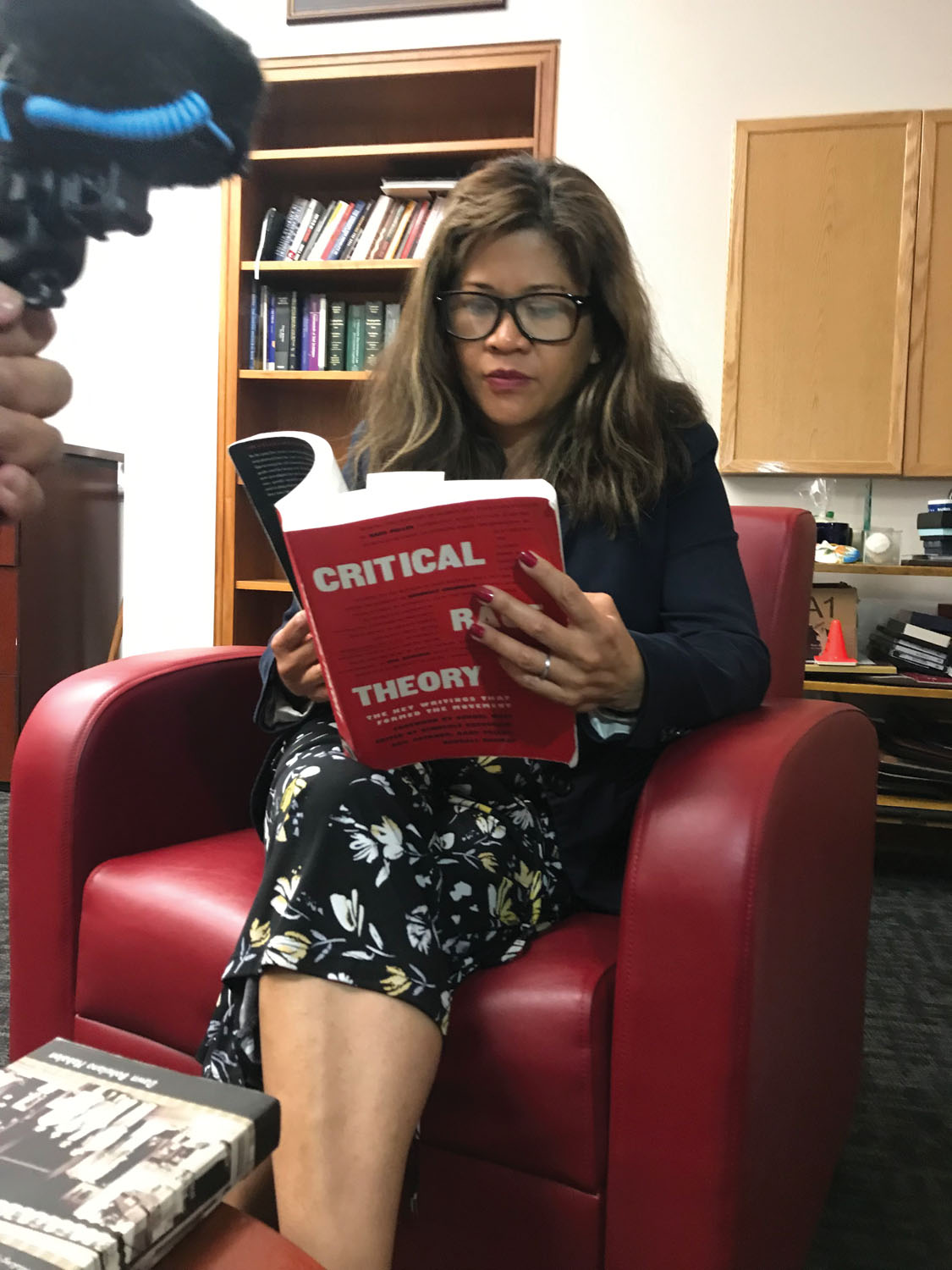

Critical Race Theory

Professor Villazor teaches, researches, and writes in the areas of immigration and citizenship law, property law, Asian Americans and the law, equal protection law, Immigration Law, Estates in Land and Future Interests, and Critical Race Theory, Her research agenda explores legal structures and systems that determine membership and sense of belonging in the United States.

She has taught critical race theory many times since she began teaching in 2006.

“We know that there are racial inequities, what are we going to do about it. Critical Race Theory asks those questions. We’re critiquing the law by taking a step back and say ‘Well, who passed these laws? What were they thinking at the time? And then what impact did it have when they passed these laws,” she explained. “And we can see through CRT that the law has not been neutral, the law has led to the subordination of people of color, of women, of immigrants, and then the next question is what do we do about it?”

However, due to misinformation, disinformation, and the proliferation of fake news, the concept of critical race theory became highly politicized.

When she sees in the news these parents who are protesting outside of school boards saying ‘don’t teach CRT to my children,’ she is in disbelief.

“First I was thinking, are they even teaching that, because that’s great if they are. And if they are teaching that, then that’s just wonderful because the history of the United States is not some glorious history as we know it,” she said. “The Philippines was colonized, Filipinos were denied citizenship, nobody knows it and critical race theory unearthed all that and says this is part of our history, and it’s important for our children to know it, or that to be taught in college and law school.”

Giving back

“I never thought I would become a dean, I just wanted to be a law professor. I also didn’t think I could become a law professor but I had mentors in law school,” she shared. “I’m an immigrant, and it’s not easy to be an immigrant, anywhere, particularly in the United States so in seeing from my own personal experience, my parents and other people around me, I’ve seen the role of law in shaping, all of those experiences.”

She is thankful to everyone who gave her a chance and opened doors for her. Without the women law professors, she wouldn’t have thought about pursuing what would become her vocation, and they gave her that impetus, served as her references, and then helped her to get the Human Rights fellowship at Columbia.

At Columbia, she had other mentors who then vouched for her and helped her to get her first teaching job.

“And so I think my path shows that it really does take a village to believe in you to help you and to lead, to help get you someplace. My goal now, I’m committed to helping college and high school students who think about becoming a lawyer. It’s my way of giving back,” she said.

“I would not be where I am today without my family. My husband is also a lawyer and so he and I have to make sure that we support each other’s careers,” she added.

Aside from the deanship. Professor Villazor is also busy with her current research projects which examine the extent to which states, cities, churches, and non-state actors such as universities and churches provide “sanctuary” to undocumented immigrants and refugees.

She is also working on two book projects: one on Asian Pacific Americans and the Law (forthcoming at NYU Press) and the other on Property Law and Race (forthcoming at Carolina Academic Press).

To de-stress, she gets together with friends who are not lawyers, because “it’s just fun to be able to hang out with others and not talk about the law”. She sometimes plays the ukulele. And of course, the occasional karaoke.

“I mean, you know, how could you not do karaoke?” she said.