Unpacking the Filipino community’s rocky relationship with mental illness acceptance

HISTORICALLY, the study of mental illness has often been referred to as “abnormal psychology.” But according to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1 in 4 people suffer from a mental or neurological disorder in their lifetime, making mental illness far more common than what is suggested by its name.

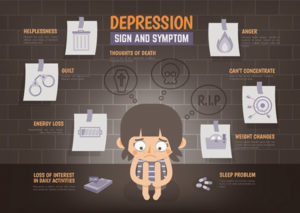

First and foremost, mental illness is exactly that: an illness. Rather than an ailment or injury to the physical body, it’s a broad range of conditions that can affect mood, thinking, productivity, relationships and behavior. But when it comes to mental health, many of us don’t treat it as an illness that needs professional medical care because of the stigmas still associated with mental disorders.

According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, more than 2.2 million Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) live with a diagnosable mental disorder.

Although Asian Americans report fewer mental health concerns, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 18.9 percent of Asian American high school students report considering suicide compared to 15.5 white students; 10.8 percent of Asian American high school students said they attempted suicide compared to 6.2 whites.

Among Filipinos, like many other cultures, mental health a dicey topic that is often ignored or packed away for fear of indignity and embarrassment within their circles. Even as many Western cultures have rallied for more awareness of the gravity of mental health, the stigma surrounding mental illness among Filipinos persists.

But just because it’s not being talked about doesn’t mean it’s not happening.

A 2014 report from the Asian American Journal of Psychology found that 13.6 percent of Filipinos are diagnosed with depression, and the CDC found that Filipina mothers are more likely to have “acute depression” and young Filipinas are “more likely” to have suicidal ideations.

So knowing all these facts and figures, it’s safe to say that mental health is an extremely important topic to discuss, without judgment, among the Filipino-American community.

Whether it’s depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder or familial and relationship struggles, mental and emotional challenges are treatable and individuals with mental illness are able to continue to function in their everyday lives.

There are a wide variety of professional mental health services available, and therapy and counseling are often the first steps people take when trying to handle the mental and emotional challenges they face.

Filipina-American Lea Mendoza is a licensed marriage and family therapist (LMFT) based in Orange County, and she says that the goal of therapy is to help carefully sort out her clients’ lives and to redirect ways of thinking that are narrowly-tailored for each client’s unique needs.

“It’s like a car tune up. You need an oil change because the oil gets gunky, but with the challenges of life, you forget about it,” Mendoza shared in a recent conversation with the Asian Journal. “It’s the same with healthy coping skills when life gets really tough, so you need a gentle reminder of those so you can go back to living your life comfortably.”

Saving face within the community

Within the Filipino community, the stigmatization of mental disorder correlates to fear of judgment from others. It’s not an open conversation Filipinos are wont to have with family and friends because, to admit that they or someone in their family is struggling mentally, would reflect badly on them, which often stops them from seeking professional help, according to Mendoza.

“As Filipinos, we were taught and raised to keep a good face,” Mendoza shared. “Put on a good front and save face and no matter what, shut up and don’t tell anyone about any challenges going on because that’s a reflection of weakness.”

She says, when it comes to Filipino parents with a child who is struggling, “it’s always about, ‘Oh, what are people going to think about me?’ but it’s never about, ‘Oh, my poor child, how can I help my child?’”

Although the potential for shame as a barrier for seeking mental health services isn’t unique to Filipinos, it’s a pervasive reason that stops many Filipinos from seeking professional help for treatable mental illnesses.

Relying solely on religion

Another common reason why Filipinos don’t actively seek out mental health services is the fact that Filipinos are extremely religious. The “bahala na” mentality is pervasive among Filipinos who solely entrust their fates to prayer and God, but Mendoza says that you can’t rely on religion without faith and you can’t have prayer without action.

“If you’re just religious, especially in the Catholic faith, you’re just doing those rituals and up the ante when things aren’t going well, so for those people everything is about prayer, but I don’t think they really connect the dots between asking and doing,” Mendoza said. “Do something to make your life better. Do something to improve your health. You can pray to God asking Him for good health but you’re doing things that don’t improve your health.

Mendoza acknowledges that faith, spirituality and prayer are important to many Filipinos, but depending on those sources to fix all of life’s problems won’t always help and, at that point, it might be time to take action and seek professional help.

“It’s like drinking acid and asking God for a miracle and then getting angry that your insides are burning,” she said. “If it’s important for you to pray, then yes, pray, but you can’t rely on that.”

Parental influence on children’s behavior

Like many LMFTs, Mendoza sees many children and adolescent clients who were brought in by their parents who think there is something wrong with their child, which she a says “is a signal to all therapists that the children aren’t always the problem.”

“It’s the environment. What are they taught? What kind of behaviors do they see? If a parent screams and yells, why do they expect their children not to do the same?” Mendoza says.

But when is the right time to seek professional services? Mendoza says that parents should keep an eye on their children’s behavior, and when things seem to be going awry, then they should have a gentle, judgment-free conversation with their children, who may have fear of reproach if they open up to their parents.

“A person usually has a baseline for their functioning. Sometimes they dip in their functioning — and everyone gets sad or nervous or anxious here and there — but if it’s so significant that the symptoms are causing problems or difficulty at school, work or with friends, then that’s when they might consider professional help,” she said.

It’s not easy to change societal attitudes about mental health overnight, but recognizing that things like depression, anxiety and trauma are illnesses rather than flaws in character is the first step to acceptance.

Mental health, just like physical health, are the main pillars of overall wellness, and it’s something Filipinos should take seriously, especially if it applies to your children, Mendoza said.

“If we’re so averse to the phrase mental health, why don’t we just change that to ‘total well-being?’” she suggested. “If your child is not thriving, it doesn’t matter what the issue is, doesn’t your heart go out to that child instead of saying, ‘tough it up and move on.’? Being tough isn’t necessarily helpful in every single scenario. There are children who bounce out of challenges right away, but there are those who need more help.”

She added: “So look at your child without comparing them to others, and if you see they are having problems, have a conversation with them, and if you can’t figure it out, don’t put judgment on them. Ask for help because there are so many resources available now. There’s no shame in asking for help.”