by Anna Gorman

AS he grew older, Dale Kunitomi paid closer attention to his health — and to his doctor’s advice. When he noticed rectal bleeding in 2010, he went to see his physician, who ordered a colonoscopy.

The diagnosis: colon cancer.

Kunitomi, now 74, underwent surgery, radiation and chemotherapy — and now he has been cancer-free for seven years. “The things that are said about early detection and living a healthy lifestyle are important,” said Kunitomi, a resident of Ventura County, Calif. “You are foolish if you don’t pay attention.”

Californians are living longer with most types of cancer, due to earlier detection and more effective treatments, according to new research from the University of California-Davis. But racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities persist, the report found.

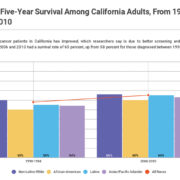

The study, published this week, shows that 65 percent of people diagnosed with cancer between 2006 and 2010 survived five years or more from the time their disease was discovered, up from 58 percent for those diagnosed between 1990 and 1994. The researchers drew from data on 1.4 million California adults diagnosed with 27 different kinds of cancer. They found improved survival rates for patients with all but five types of cancer.

Non-Latino whites had the highest five-year survival rate for all cancers combined, followed by Latinos — though Pacific Islanders and Asians, like Kunitomi, had the highest rates for 13 of the cancers studied, including breast, colon, liver and lung. African-Americans had the worst overall prognosis.

The California numbers echo a national trend of significant improvement in cancer survival, one also tempered by racial and ethnic disparities. A recent analysis in the journal Cancer, which relied on death rather than survival rates, found a 26 percent decline in cancer mortality in the United States between 1991 and 2015 — translating to nearly 2.4 million cancer deaths avoided. The study showed mortality rates declined for all the major cancers, including breast, colorectal and prostate.

Dr. Otis Brawley, one of the authors of that report and chief medical and scientific officer of the American Cancer Society, attributed the improvement to better screening, detection and treatment — and a decline in smoking. He said cancer deaths likely would drop even further if there were more equal access to prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the UC-Davis data show that poor Californians don’t live as long with cancer as those of greater means. About three-quarters of the patients at the highest socioeconomic level, with all cancers combined, survived five years or more. Just over half the patients at the lowest levels lived that long. Age was also a major factor: The younger patients were at the time of the diagnosis, the better their chance of survival.

Separate research from UC-Davis, published in 2015, showed the impact of health insurance status: Uninsured patients and those on Medi-Cal — California’s version of the federal Medicaid program for low-income people — had worse cancer care and outcomes than people with private insurance.

The research published this week showed the most critical factor in survival was finding the cancer early, which the report said underscores the importance of screening. One hundred percent of breast cancer patients survived at least five years if their disease was detected at stage 1. Only 28 percent of patients lived that long if their cancer was found when it was at stage 4, the most advanced stage. Most types of cancer show similarly stark disparities.

Stages, which depend in part on the size of the tumor and whether the cancer has spread, are a gauge of how serious the disease is.

“The earlier things are picked up, the more likely it is that treatment is successful,” said Dr. Kenneth Kizer, senior author of the study and director of the UC-Davis Institute for Population Health Improvement.

Cancer screening and treatment for African-Americans lag behind other racial and ethnic groups, said Dr. Nancy Lee, who is on the board of Black Women’s Health Imperative, a national organization that seeks to improve the health of black women. Long-standing and sometimes unrecognized bias in the health care system disadvantages black patients in a way that can compromise their medical outcomes, said Lee, who previously led the cancer division of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

White women in California are more likely to get breast cancer, the most common cancer among women, but black women are more likely to die from it, the UC-Davis report found.

Bobby Smith’s wife, an African-American, died 13 years ago after her breast cancer moved into her lymph nodes and eventually metastasized to her brain. Smith said he doesn’t believe doctors gave her all the information she needed to make the best decisions about her treatment. “Health care professionals treat and serve people of color differently,” said Smith, who lives in Los Angeles.

The UC-Davis report used data from the California Cancer Registry, a repository of data on cancer patients dating to 1988 that contains information on patient demographics, diagnosis, initial treatment and outcomes.

The rates reported in the study measure “relative” survival, which represents survival in the absence of other causes of death. The study showed patients with prostate, breast, melanoma and uterine cancers had among the highest survival rates: More than 80 percent of them lived at least five years after their diagnosis.

Survival did not improve for patients with some cancers, including bladder, cervical and testicular. And fewer than 20 percent of patients with cancers of the lung, liver, pancreas and esophagus lived past five years.

For breast cancer patients, five-year survival improved from 85 percent among those diagnosed between 1990 and 1994 to 90 percent among those diagnosed between 2006 and 2010.

The patterns were similar for lung cancer, the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in California and the leading cause of cancer deaths nationwide. The disease tends to be diagnosed late, and patients with stage 4 cancer had just a 4 percent survival rate after five years.

Kizer of UC-Davis said new treatments offer great promise for cancer patients, but how much money they have and who their insurers are may well determine whether or not they reap the benefits.

Cancer is hard enough for people with means and education, said Susan Lasker Hertz, 61, a Colorado nurse who was diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer in 2009 and then developed leukemia three years later. Hertz, who is now in remission from both cancers, said her knowledge and experience helped her navigate the health care system and get treated quickly after her diagnosis. But it wasn’t easy.

“I am an educated, white, highly knowledgeable health care professional,” she said, “and it is still overwhelming.”

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation.