By Cid Reyes

OF certain artists, it can be said that they paint with such joy and exuberance as if abstraction had never been discovered, as if their hands were the unconscious mind plumbing the depths of some heretofore hidden well of forms and colors never beheld in visible reality.

So stirred and thrilled is their spirit that they take to abstraction like a duck to water, buoyed up by a sensibility clearly in its nascent stage.

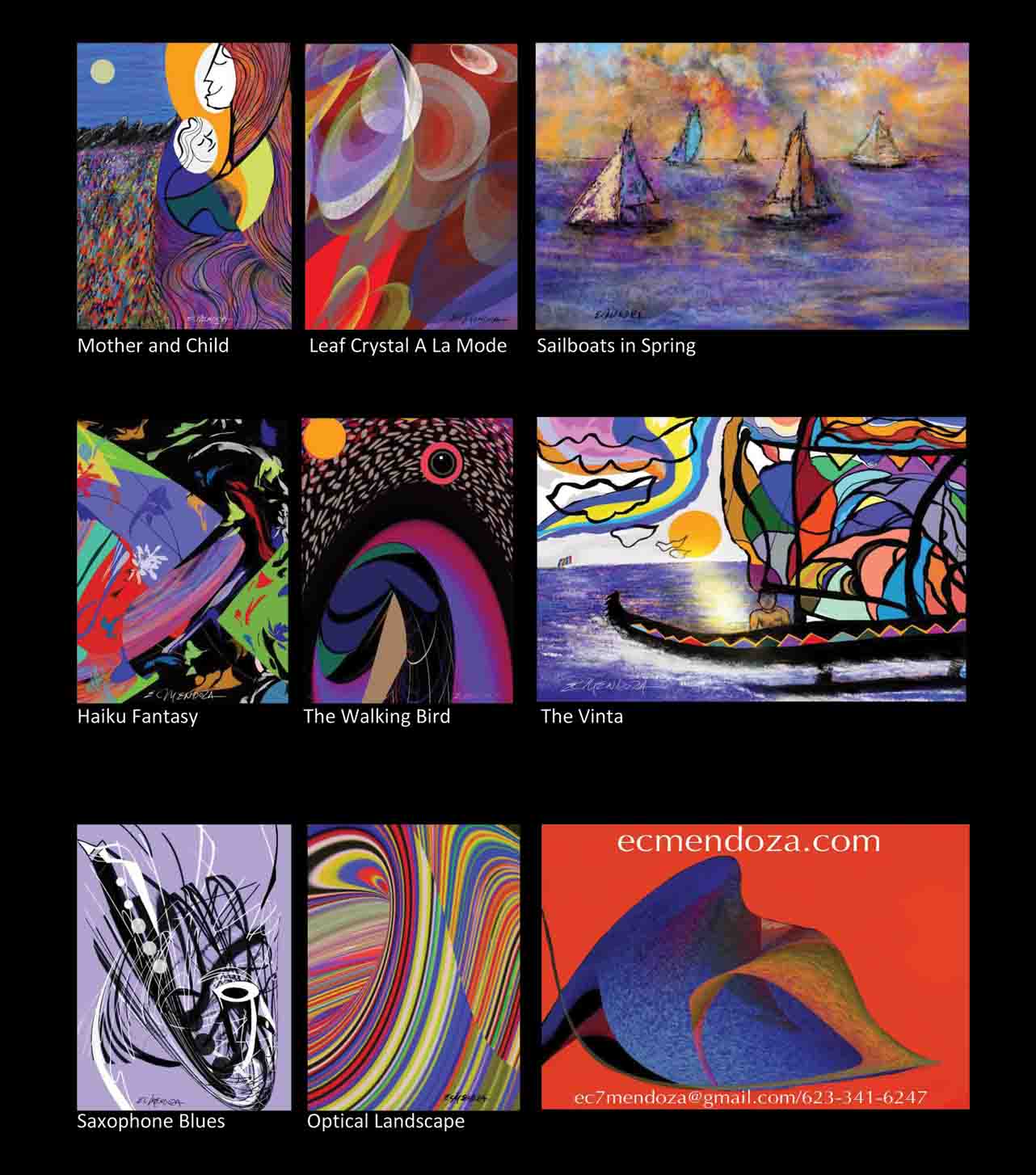

Filipino American artist Errol Mendoza is one of them. Considerably a late starter in the active practice of artmaking, Mendoza is now painting as if there were no tomorrow. To be sure, while the triggering impulse is to make up for lost time, he can only trust his instinct as he voyages into the unknown.

Giving free rein to instinct

Mendoza is propelled by the immediacy of the moment and, being innately adventurous and venturesome, he was not anxious about finding a distinct style for himself, knowing that it will emerge naturally through his choice of themes and subject matter. Will he be derivative or will he be eclectic? Neither it seemed was his concern. He would instead choose a subject, universal ones such as nature and the seasons, time of the day, emotions and feelings, music and, intriguingly a personal predilection, digital technology. Mendoza decided that he would simply give free rein to his instinct, giving no opposition to where color and form would lead him.

High-spirited playfulness

As it turned out, the engine that would drive Mendoza’s composition was a conflation of motion, movement, dynamics, rhythmic pattern, flux, flow, fluidity, unrest…Yet all these would be tempered by the grace of lyricism and a high-spirited playfulness. In works like Fields Unfolding, An Ode to the Wind, Into the Woods, and Leaf Crystal, one senses a current of movement and counter-movement, the swirling lines pulled relentlessly in shifting directions. The music-inspired works, like The Trio, The Pianist, Saxophone Blues and The Gypsy Violinist are marvels of fragmentation, shards of planes that are themselves thrown into rhythmic syncopation.

Recollecting dance

And if music, the art of sounds in the movement of time can inspire Mendoza, so much more can dance, regarded as the most perishable of the arts. Martha Graham herself confirmed that dancing is essentially of the moment and nothing is left but the pictures and the memories. And in Mendoza’s paintings titled The Tango, Op Ballet, The Rite of Spring, and Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana Ballet, the artist’s recollection of certain dances leaps off the canvas surface, ricochets around its space, and through spinning lines and driven angles, the viewer can feel the impulse of the bodies’ poses, the gestures of hands and feet, and those applause-generating pointes.

From something so innately lyrical and graceful, Mendoza can just as easily shift to the automated and technical: computers, robotics and machinery electronics. The computer circuit boards that are transfigured in Microchipped and Within a Pixel advert to painting’s capacity to work hand in hand with digital technology.

Framed tableau

Interestingly, Mendoza’s penchant for painting in diptychs and triptychs suggests a voraciousness for space, implying that the forms contained in one work irresistibly needed to extend themselves onto the next of the series, such is the energy and vitality and fertility of the still aborning forms. In triptych and quadriptych works like Fleur, Haiku Imagined, Memory of a Mist, Unfinished Sky, Sand Dunes in Time, Linear Mythology and The Color of Sound, they are framed by the eye as a tableau, though each one has its own distinct identity and can very well stand on its own.

A romp and a prance

And while Paul Klee defined a line as “a dot taken for a walk,” it seemed that Mendoza had meant to outdo the Swiss master. Indeed, he had taken a dot for a romp and a prance, twisting and spiraling, streaking and charging, in wild hoops and convoluted coils, as the bounding lines transformed into a myriad of shapes and contours. Mendoza’s quirky and zany and jazzy lines are best appreciated in works like Linear Regatta, At The Beach, The Mountain Resort, and — as a bow to his country of origin, the Philippines, The Vinta, those colorful sailboats in the tropical archipelago’s largest island of Mindanao. All these works are an eyeful, leading one to think that Mendoza had taken his lines out on a holiday.

Arcadian realm

The advantage of Mendoza is that he has not yet fallen into mannerisms, idiosyncrasies and eccentricities — alas, vices that are engendered and encouraged by newfound fame and fortune. For artists like Errol Mendoza for whom artmaking is a joint venture with his instinct, visual intelligence and frisky imagination, abstraction can be generous, opening up the bliss of its arcadian realm.

“Look in the Mirror”

A popular quotation goes: “Look in the mirror…That’s your competition.” More appropriately for an artist, it should be: “Look at the canvas…That’s your competition.” Optimistically, an artist’s best work should be his next. For only in “conquering” his pictorial space will an artist prove his mettle. Art competitions, of course, are the traditional arena where art gladiators battle it out. In Glendale, California, where Mendoza is based, the century-old Glendale Art Association has been host to such competitions, and where Mendoza has avidly participated. To date, he has won First Place, four times; once in Second Place; and three times in Third Place.

The Walking Bird

Incidentally, another cause for celebration is the choice of an Errol Mendoza artwork as the cover illustration for The Walking Bird, the “collected words” of the British poet M. F. Gordon. Presciently, the title poem conveys a knowing tone, bearing the lines:

Why the need

To paint a dot.

It will only

dry.

Crack with

a sharp sting

crumble,

following me

to earth.

In contrast to Mendoza’s unmistakably jaunty way of composing a painting, Gordon’s tightly columnar length of lines, sustained unwaveringly throughout the entire book, betokens a disciplined spirit and a solitary approach to poetry. For some reason, the reader will perceive that these poems are the equivalence of the journals of a reflective and observant man, given to noticing and finding revelation in a Cheshire cat, a girl’s blouse, his bank account, a bathroom door unlocked, the gathering lines on the poet’s aging face, a one-night stand, and sleeping in public. While the diction is colloquial and informal, Gordon’s poetry, while restrained and reserved, is rich with an awareness of human intimacies (When you/ undress/ or dress,/ as if I’m/ not a man) and failings (Sad man,/ sitting/ at a bar…Never fulfilled./ Only refilled,/ glass after glass.)

When British poet M. F. Gordon and Filipino American painter Errol Mendoza meet on the cover of The Walking Bird, something universal this way comes.

* * *

Cid Reyes is the author of choice of several Filipino National Artists. He has written over 40 art books and numerous reviews and exhibition essays. Reyes received a “Best in Art Criticism Award” from the Art Association of the Philippines.

What joy to revel in Errol Mendoza’s beautiful paintings, an experience made even more meaningful and valuable by Cid Reyes’s erudite, insightful, and eloquent essay. Thank you, Asian Journal, for gifting the reader’s mind, heart and spirit with this delightful melding of colors and forms with words and verbalized ideas.