The journalist and activist explores the meaning of home, internal identity struggles and the power of speaking up in new memoir “Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen”

Two things happened to Jose Antonio Vargas after Donald J. Trump was elected the 45th President of the United States of America.

First, he found himself without a permanent residence. On the day after the election, on Nov. 9, 2016, Vargas was living in an upscale apartment building in Downtown Los Angeles. The building’s manager, with whom Vargas had a friendly acquaintance, texted him saying “I’m not sure what we could do if you showed back up here,” suggesting the likelihood that Vargas would be apprehended under Trump’s stringent immigration reforms.

“[James] Baldwin once said, ‘All safety is an illusion,’ and that never felt more real than that day,” Vargas told this writer in a recent phone interview. Vargas proceeded to move out of that apartment building.

The second thing that happened was a sudden flood of emails, tweets and messages from young, undocumented immigrants to Vargas, who for the last decade has become a reverberating voice in the fight for immigration reform and immigrants’ rights.

Across the country, the undocumented community feared for their futures in the U.S. and turned to the strong-willed, defying voice that Vargas lent in the national dialogue on these issues, and the 37-year-old writer and activist wanted to deliver in the form of a book.

Originally, he had planned on an issue-based book of the global impact of immigration policy, but his editor, instead, asked him to list out the top 10 most painful experiences of his life, “all of which had to do with lying, passing or hiding,” Vargas said in the interview.

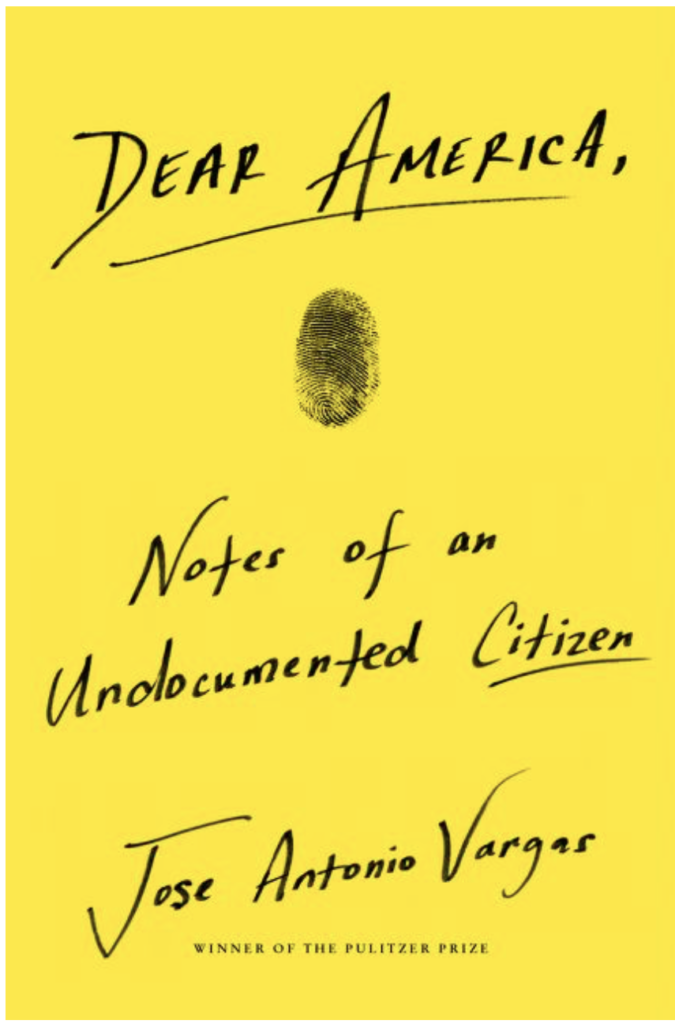

This became the foundation of his newly-released first book, “Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen,” a powerful, unmitigated memoir which has less to do with immigration policy and the politics surrounding it, but more to do with the psychological and emotional implications of living in America as an undocumented person.

Vargas has propelled his message through the affecting cogency of his journalistic writing (like in his 2011 New York Times essay in which he made public his citizenship status) and documentary filmmaking that thematically challenges social and political norms. He’s harnessed his message into founding Define American, a non-profit media and culture organization focused on immigrants and their stories rather than politics.

Vargas began “Dear America” after he left his downtown LA apartment and began his nomad lifestyle, staying with friends or renting out hotel rooms and Airbnbs. As he writes in the prologue, the book appeals to the feeling of homelessness and living a life where he had to hide from the government and lie about his citizenship.

But this time around, Vargas wanted to strip the story of policy jargon and political rhetoric and put together a narrative with language that’s “more accessible and relatable” to relay a more human element of an oft-dehumanizing topic.

“After twenty-five years of living illegally in a country that does not consider me one of its own, this book is the closest thing I have to freedom,” Vargas writes in the book’s prologue.

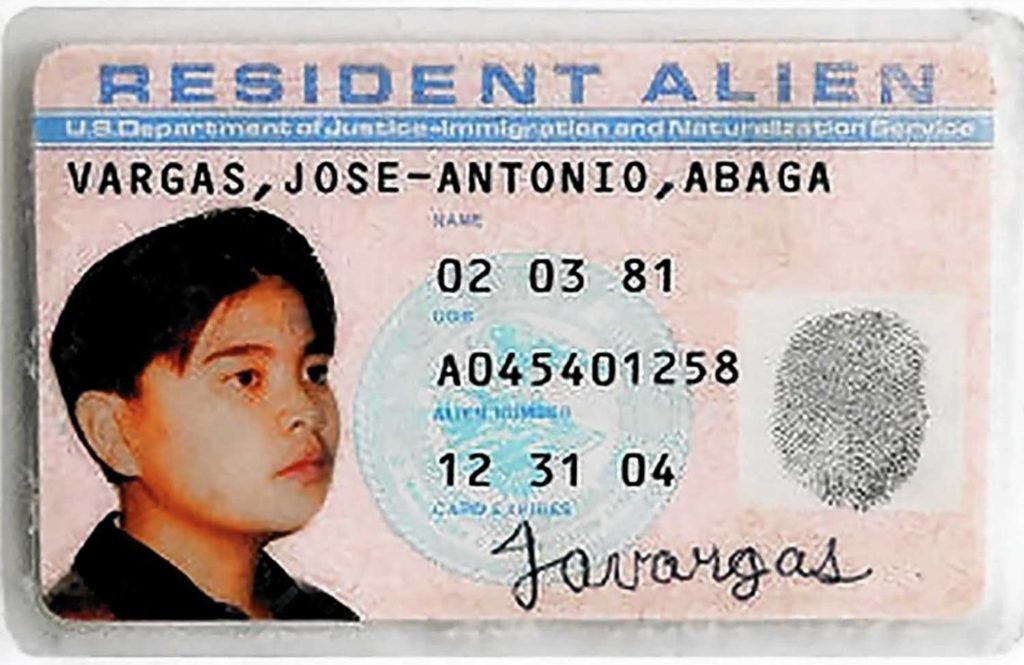

In the book, Vargas details — through succinct, but stirring chapters — his mother sending him from Antipolo, Philippines (where he was born) to Northern California in 1993 to live with his lola and lolo. He recounts the shock and horror he felt as a teenager when he found out that he was undocumented and how coming out as undocumented was more difficult than coming out as a gay man.

For those of us who haven’t gone through life as an undocumented immigrant of color, it’s difficult to imagine the emotional rigmarole that comes as a requisite for undocumented peoples in an America where the emergence of nativism and xenophobia continues to manifest itself in the ugliest ways.

“Dear America” delivers a perspective that has endured institutionalized and socialized racism and internal struggles and identity crises as an undocumented gay immigrant of color.

“The book is kind of owning up to my own depression that I don’t really talk about. I wanted to create something relatable, but I wrote the book, really, for myself, and it’s probably the closest I ever got to going to therapy,” Vargas quipped in our interview.

Impactfully, he references his literary idols — celebrated black American writers Toni Morrison and James Baldwin and legendary Filipino-American writer and poet Carlos Bulosan — writers of color who, unapologetically, claimed their identities and reverberated their truths through their writing — and, it’s evident throughout “Dear America” that he’s following suit.

He began writing the book at the dawn of 2018 and chronicled the invisible existence he’s lived throughout his life as the Trump administration rolled out its most controversial immigration measures.

“We are flooded with news about immigration, and sometimes the media makes it seem like all of this is happening all at once, but the reality is that Trump is only the culmination and manifestation of every bad policy on immigration. This did not happen overnight,” Vargas says.

When news came out that migrant families were being separated at the border in the early summer, he was simultaneously recounting his own detention long before Trump’s election, in the summer of 2014 when he was detained with young Hispanic boys in a jail cell in south Texas, when “the media didn’t care and there were no hashtags or marches to bring families together,” he laughingly tells me.

In this poignant chapter, Vargas details the language barrier between these boys and him and the desire to assure them colonialism was the root cause of the unjust, inhumane immigration practices that America, a country founded by immigrants, has adopted.

“If I spoke Spanish, I could have told the boys that none of this was their fault,” Vargas writes in the book. “I could have made sure they understood — even if most Americans do not — that people like us come to America because America was in our countries.”

The physical book, itself, also emphatically represents Vargas’ claim of identity and voice with the handwritten cover title and byline, Vargas’ fingerprint as the cover art and the bright, Pantone yellow book jacket that represents the given color of the Asian race.

In a chapter called “Filipinos” he writes, “Filipinos fit everywhere and nowhere at all,” and despite the rich presence of Filipinos in American history, the struggle of Filipinos in America to feel at home and to feel a sense of belonging is ubiquitous.

In our interview, Vargas notes the present reckoning of Filipino-American writers like Noel Alumit and Elaine Castillo who are “redefining and claiming” the Filipino identity in the 21st century. In many ways, “Dear America” is an introductory call to Filipinos in America — undocumented and otherwise — to stake a claim to the Filipino-American identity and understanding how we got here.

At the time of publication of “Dear America,” Vargas is 37 years old, one year older than his mother was when she dropped him off at the airport in the Philippines.

On Sept. 25, on a speaking tour for his book at University of Southern California, Vargas requested that he record the audience singing “Happy Birthday” to his mother, who turned 61 years old that very day. Vargas has not seen his mother in person since that day at the airport 25 years ago.

Publicly, Vargas is a fierce, outspoken advocate for the humanization of the immigration conversation. But on that day at the Bovard Auditorium recording a crowd of strangers wish his mother a happy birthday, his demeanor softened and a modest, faint smile formed on his face.

At that moment, Vargas wasn’t an activist or a writer. He was the son of a Filipina who risked family separation for the success of her anak.

“Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen” is out now.

After 25 years, he continues to milk his undocumented status as an illegal alien. People with less talent and opportunity than he has have been able to gain legal status yet Vargas with all his connections and talent seems to enjoy being an illegal alien and make money off it. If he gains legal status he would no linger be relevant in the illegal alien community as he would be just like the rest of us.

would love to read the book..had the chance to read Carlos Bulosan’s book,great experience..