Commenting on my previous essay entitled “Utang na Loob,” (published in the Los Angeles Asian Journal issue on July 29, 2020), a family friend wrote: “Why did Asians rise a bit higher than Blacks? Is it their thirst for a good education, a lot of self-esteem and pride in their heritage as well as close family ties that encouraged them to target a higher vision?”

To this, I am tempted to just give a short answer. The idea that Asians, particularly Filipinos, are “better” than blacks is a key ingredient of that kool-aid that we have been drinking as former colonial subjects. It is a wedge intended to divide us in the manner of “divide and conquer” from other communities of color.

As former colonial subjects of the United States, tutored via an American style educational system — which historian Renato Constantino singles out as the main reason for the miseducation of Filipinos — we have a baked-in inferiority complex about white Americans. So it feels good to hear that we are better than Blacks, and eagerly subscribe to the “model minority” myth.

This is the idea that Asians, despite a shared history of racial discrimination with blacks and Native Americans, have been able to overcome their marginalization due to a strong work ethic and family values. And have become America’s model minority.

When the idea was first proposed in the mid-1960s, amid protests for civil rights led by African Americans, it was intended to minimize the demands of African Americans, by saying: “Look, if Asians can rise above their oppression and marginalization, then African Americans can too — under the current system — if they adopt the values that make Asian Americans successful.” This is a well-worn but dangerous cliché that white privileged America has fomented upon blacks, and Native Americans to minimize their demands for equality. It is not only misleading, it drives a wedge between Asian Americans and African Americans. For Filipinos who have been miseducated into thinking that their culture is inferior to white western culture, it feels good to hear that there are others in America, Blacks, who are inferior to us. We eagerly and uncritically drink the kool-aid.

I do not dispute that our community today, exudes an image of success, and that on a per capita basis, we are doing better than African Americans. But I do not believe that we have overcome in the sense that our values have enabled us to transcend racial oppression and marginalization.

Let me explain. Statistically, our community now numbers over 4 million (2018 American Community Survey) yet the majority of our community (69%) are foreign-born or immigrants. This means that immigration played a huge part in shaping our community. Immigration is the selective recruitment of Filipinos where priority is given to the highly educated and skilled. We have heard of the term, “brain drain” where the brightest, most highly educated and trained Filipinos are recruited away from the Philippines to work in another country, such as the United States.

Through selective recruitment, aka immigration policy, more than 2/3rds of our community are among the most educated, most skilled, and the most motivated among Filipinos. They mostly come from middle-class families who can take advantage of educational opportunities in the Philippines, and leverage these for jobs abroad created by labor shortages in different sectors. My brother, a civil engineer and computer programmer with experience in the petrochemical industry, was able to immigrate with his whole family (wife and three children) due to a severe labor shortage of computer programmers to fix the Y2K bug, a couple of years before our calendars turned over into the year 2000. Around the same time, I met a group of Filipino teachers in science and math, fresh off the boat, so to speak, who were recruited to fill shortages of math and science teachers in Los Angeles County. These are not individuals who experienced racial bigotry growing up. They do not come from families who have been historically denied educational opportunities and jobs. And who had to struggle against discrimination, poverty, and a history rooted in slavery.

There is an ironic twist in our historical confrontation with American style white supremacy. At the turn of the 20th century, America sought to annex the Philippines as a colonial territory. Filipinos who had just declared independence from Spain resisted that effort. We lost that war. As a fig leaf for their intentions, the U.S. declared a policy of “benevolent assimilation.” This led, among other things, to the establishment of a nationwide system of public education, and the recruitment of thousands of white teachers to teach at these schools. Americans even established a public university, the University of the Philippines (1908) to give Filipinos access to American style higher education. Since the early decades of the 20th century, Filipinos were being given access to educational opportunities that were being denied African Americans by Jim Crow laws.

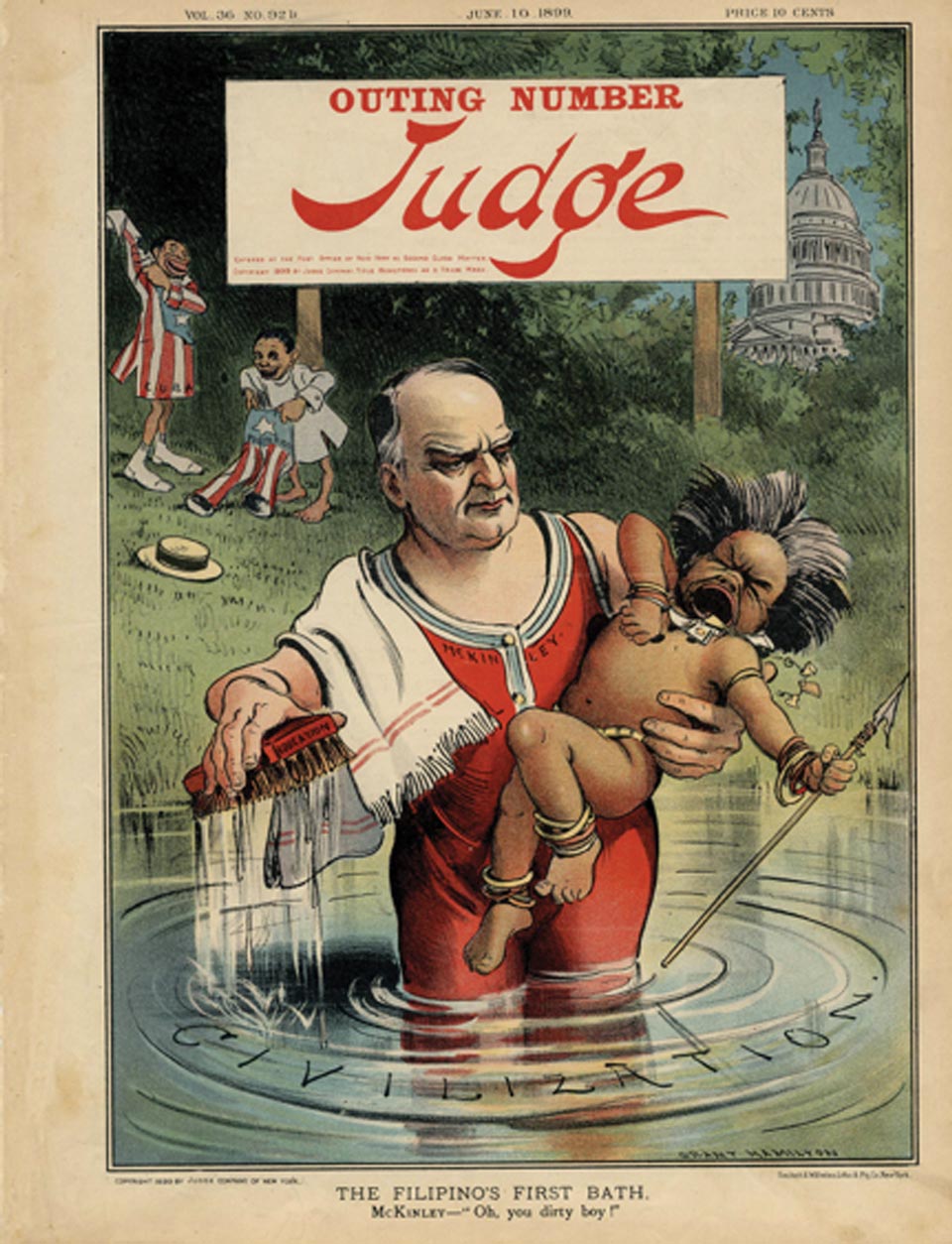

To be sure, the policy of Benevolent Assimilation was racist at its core since it presupposed that we were subhuman, illiterate savages no different from African Americans. Ample evidence of this is provided in a book, which I co-authored, “The Forbidden Book,” a collection of editorial cartoons from the Philippine-American war period. Contrary to our depiction as subhuman savages, by mainstream American media of the period, we had an educational system that included the University of Santo Tomas, a European style university founded 30 years before Harvard. We had painters like Juan Luna who were winning awards in Europe, writers like Jose Rizal, whose work was admired even by the Spanish. His two novels, “Noli Me Tangere” and “El Filibusterismo,” were unfortunately thought to have incited the rebellion against Spain, and Rizal was arrested and executed him for them.

The American style educational system did turn us into docile colonials for American purposes, a model minority that they could hold up against African American demands for freedom and equality.

This disparate treatment between African Americans and Filipinos, plus the selective recruitment of Filipinos via immigration, is largely responsible for the disparate conditions between Filipino and African American communities today. The wedge created by the model minority image enabled Filipinos to occupy that liminal space between white privilege and white supremacy, African Americans meanwhile continued to be kept across that border defined by white supremacists.

Filipinos in America have been spared the worse effects of white supremacy by our initial resistance against white America’s efforts at empire. But we have a brotherhood with African Americans that extends back to the Philippine American war when black soldiers broke ranks with their white counterparts and defected into the Filipino rebel army.

One such noted soldier is David Fagan, of the 24th Regiment of the U.S. Army. Fagan’s heroic exploits with Filipinos even drew notice from the New York Times. He was our “General Lafayette,” in our war against American imperialism.

Our robust presence here today, where our communities are able to flourish in the space opened up by historic civil rights legislation passed in the 1960s, is owed to African Americans and their allies who dared to confront racism and white supremacy. We have to be critically wary of suggestions that it is our family values and work ethic that set us apart from African Americans. Those are the myths in that kool-aid calculated to divide us from other communities of color.