Bini in 2024 (left to right): Stacey, Aiah, Colet, Gwen, Mikha, Sheena, Jhoanna, and Maloi

By 티비텐, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=151979473

In smoky karaoke bars, Manila traffic jams, and diaspora homes across the globe, Filipino music has always played in the background—comforting, familiar, and deeply emotional. From the sentimental chords of ballads to the rhythmic warmth of folk, the Philippines has long been a nation defined by its love for song.

But in the 2020s, a different kind of sound began shaking the speakers: faster, sharper, synchronized, and unapologetically modern. Enter P-pop, or Pinoy Pop—a genre and movement that’s not just remixing global pop formats, but asserting a new generation’s sense of self, identity, and ambition.

And at last, the world isn’t just listening—it’s watching with curiosity, admiration, and intent.

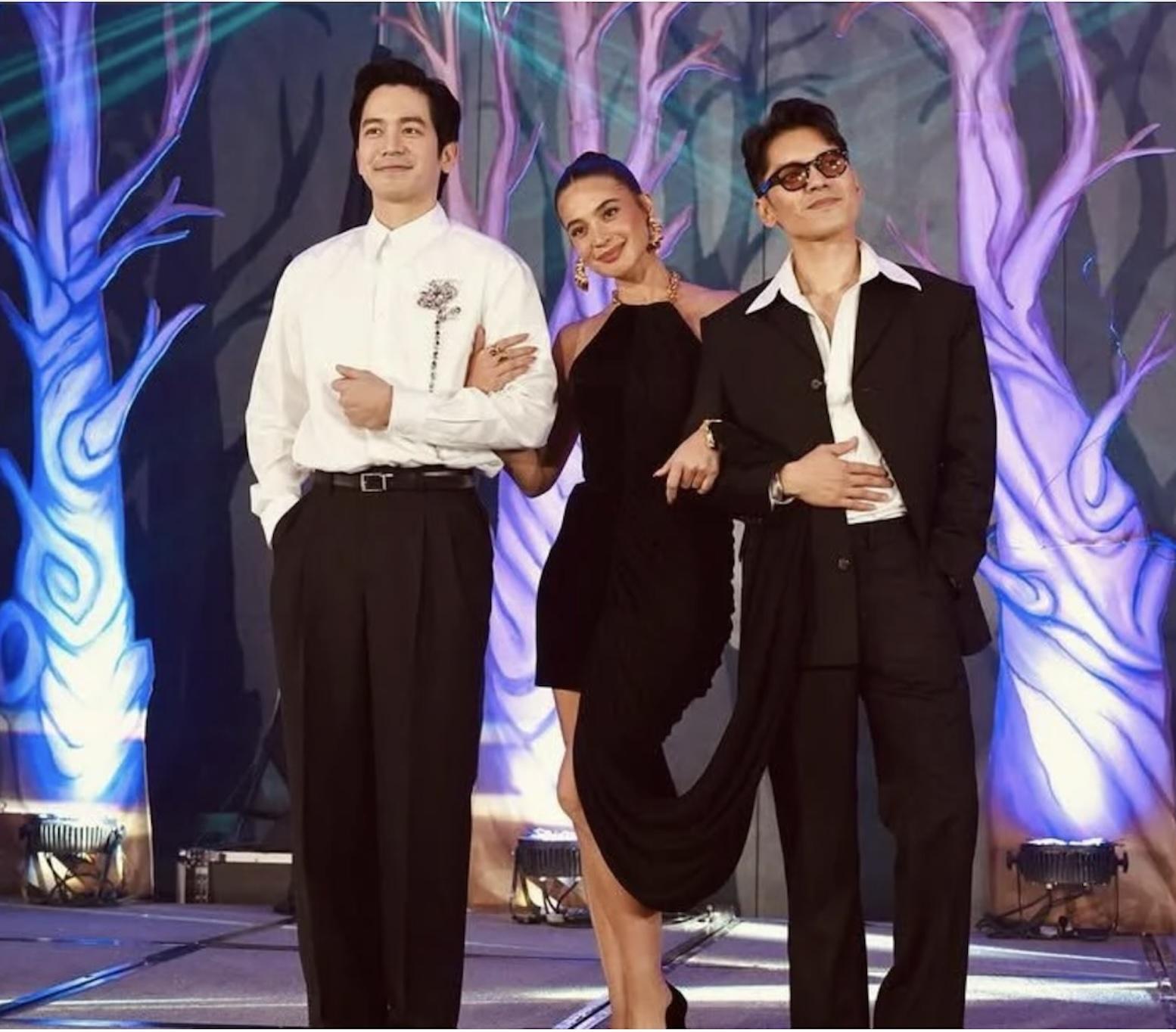

By TV Ten Asia – YouTube – View/save archived versions on archive.org and archive.today, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=151897929

The Birth of a Movement

P-pop isn’t a new term. It loosely referred to mainstream OPM (Original Pilipino Music) in the 1990s and early 2000s. Acts like Smokey Mountain and Sarah Geronimo offered early glimpses into pop commercialism. But the current wave of P-pop is different: intentional, structured, and globally competitive.

That breakthrough came in 2019 with the rise of SB19, a five-member boy group trained under the Korean company ShowBT Philippines. With their breakout hit “Go Up,” the group showcased synchronized dance, strong vocals, and heartfelt lyrics—all in Filipino. It wasn’t long before they made history: SB19 became the first Southeast Asian act nominated at the Billboard Music Awards, competing alongside BTS.

In 2023, they landed on Forbes Asia’s 100 Digital Stars list, recognizing their influence across the region for not just chart performance, but their impact on culture, advocacy, and digital engagement. Their sold-out shows, international tours, and social media activism have cemented them as pioneers—not just of P-pop, but of modern Filipino global representation.

“We carry the flag in every performance,” said leader Pablo in an interview. “It’s not just about music. It’s about telling the world who we are.”

Their success opened the door for others—but it was never a solo act.

The Rise of the Nation’s Girl Group

Hot on their heels came BINI, an eight-member girl group formed by ABS-CBN’s Star Hunt Academy. Trained in vocals, dance, media handling, and cultural awareness, BINI officially debuted in 2021 with the fierce and vibrant anthem “Born to Win.”

Their name itself—BINI, short for “binibini”—is more than a label. It’s a declaration. A nod to the traditional term for “young Filipina,” now reimagined for the 21st century: proud, modern, powerful.

Each member—Jhoanna, Aiah, Colet, Maloi, Gwen, Stacey, Mikha, and Sheena—represents a unique aspect of the contemporary Filipina. Their music blends upbeat electro-pop with affirming, Filipino-language lyrics. Their styling fuses streetwear with modern Filipiniana. Their message is consistent: “We’re not just performers—we’re symbols of strength.”

In 2023, BINI also made headlines when they were featured by Forbes Asia, recognized as one of the fastest-growing music groups in Southeast Asia. Their visibility extends across international streaming charts, fashion partnerships, and social impact campaigns—from girl empowerment to mental health awareness.

Cultural Identity Meets Idol Culture

P-pop is not just a sound—it’s a redefinition of what it means to be Filipino in the global pop arena. Drawing from the technical excellence of K-pop and the emotional storytelling of OPM, P-pop groups are now incorporating cultural references, regional languages, and social themes into their brand.

ALAMAT, for example, is a multilingual boy group using Ilocano, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Bisaya, and more in their lyrics. G22, BGYO, and VXON have all released songs tackling self-esteem, generational pressure, and Filipino resilience.

Even fan culture has localized. SB19’s A’TIN and BINI’s Blooms don’t just stan—they organize charity drives, community events, and advocacy campaigns.

“We’re not just artists, we’re bridges,” said Colet of BINI in a panel appearance. “We help people connect with who they are—and who they can be.”

The Soloist Surge

P-pop is more than groups. Solo acts are now shaping its emotional depth.

Zack Tabudlo, whose songs “Binibini” and “Pano”

Felip (SB19’s Ken) leads the genre’s experimental wing, fusing trap and spoken word with raw intensity in solo tracks like “Palayo” and “Bulan.” And rising stars like Janine Berdin and Denise Julia bring alternative, indie-pop vibes into the mainstream—with lyrics reflecting anxiety, love, and coming-of-age in the Philippines.

What Makes This Era Different?

Several forces fuel the rise of P-pop:

- Digital Infrastructure: YouTube, TikTok, Spotify, and Twitter allow artists to build fanbases globally—beyond radio play or TV appearances.

- Youth-Driven Nationalism: Young Filipinos are reclaiming language, fashion, and values—and P-pop gives them a voice.

- Industry Investment: Training academies, production houses, and media partnerships now back idol talent with serious resources.

- Community-Led Ecosystems: Fan groups are creating the kind of organized, sustained support once seen only in K-pop fandoms.

In a post-pandemic world yearning for connection, Filipino youth are finding belonging through music that mirrors both their struggles and dreams.

Where P-pop Goes From Here

P-pop still faces industry challenges: limited traditional airplay, comparison fatigue with K-pop, and the need for sustainable, long-term talent development. But its momentum is undeniable.

International fans are discovering the genre not as a copy—but as a discovery. Western media outlets are covering SB19 and BINI. Filipino groups are being invited to festivals across Asia and the Middle East. And slowly, global playlists are adding more songs in Tagalog.