Jeremy Lin, an Asian American basketball star who helped add “linsanity” to our vocabulary a few years back, now adds “coronavirus” to our glossary of racial slurs against Asians.

Lin disclosed that he has been called, “coronavirus” during a game, revealing this incident in a social media post denouncing racism against Asian Americans,

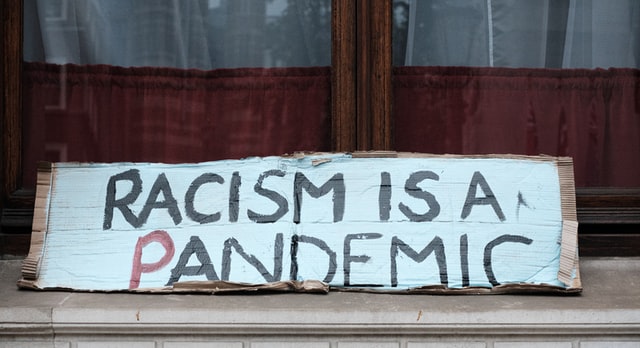

Lin’s experience is only one in a disturbing trend. Asian Americans, and Asians in other countries, report that they are experiencing harassment related to the pandemic. They range from microaggressions — comments and actions that subtly express prejudice — to violent attacks. I will call these BMA, short for Bias Motivated Aggression.

As an Asian American historian, the growing list of these incidents reminds me of our rather long history of being the targets of discrimination. The most salient examples were the incarceration of Japanese Americans during the Second World War for looking like the enemy, and the various Asian exclusion laws.

I know that anti-immigrant feelings are often aroused as public policy, and public health issues involving immigrants become salient. The upturn in BMA against Asian Americans may well derive from latent anti-immigrant feelings. The pandemic has provided an excuse to act on them.

Filipino Americans are still largely an immigrant community. Like other immigrant communities, we would much rather just ignore these microaggressions, and move on.

Our focus is on getting along in this our adopted country; we expect some resentment against our presence but we feel mostly welcomed by our American co-workers and associates. Thus, many Filipinos, particularly the foreign-born, are hesitant to get involved in the struggles against racism, even as we are now the targets of BMA, arising from the ignorance and fear surrounding the coronavirus pandemic.

In a previous essay (Asian Journal 2-27-21), I suggested that hate speech and other forms of bias-motivated behavior must be made visible so that perpetrators will not feel safe in committing aggressions. Like sexual harassment, BMA which are not brought to light emboldens the aggressor. They feel safe since their aggression carries no negative consequences for them, but their victims are hurt, stung by a stigma of being undesirable.

But making BMA visible is easier said than undertaken. There is always a chance that the aggressor, upon feeling a pushback, might escalate the aggression. It takes courage to push back against BMA; it also requires a supportive environment. Media personalities and public figures probably have the best leverage in calling these out. Lin is to be commended for his courage in calling out his personal experience with BMA while also denouncing racism against Asian Americans.

Despite what one may think, calling out BMA, or protesting against racism by public personalities carries risks. Notice how Colin Kaepernick, the San Francisco 49ers quaterback who led his team to a Super Bowl appearance remains unsigned to this day for kneeling during the national anthem—rather than standing which is customary. His protest received highly polarized reactions with Donald Trump even joining the fray by calling on NFL owners to “fire” players who protest during the national anthem.

Despite risks to victims of BMA, I believe that making BMA visible is an effective way to expose racism against Asian Americans. There are four steps to this process.

1. A crucial step is to document the incident, if you have been a victim.

2. Call it out, if one can safely do so, as Jeremy Lin did, but be factual. Social media now gives us a voice, and a platform for this. Think of it as a form of counter-speech against those who spread disinformation and hate.

3. Report it on the several websites of organizations that provide resources and gather data about BMA incidents.

4. Lastly, report it to law enforcement organizations and administrative bodies that oversee workplaces. If it rises to the level of a crime, law enforcement is duty-bound to investigate. Even if it doesn’t, administrative bodies that oversee professions and workplaces may feel the need to investigate it. As a result of Lin’s disclosure, the NBA has stated that it will look into the incident. If anything, the attention generated from Lin’s disclosure acts as a deterrent. It attaches a social stigma, a counter social stigma to BMA.

The imperative to make BMA visible is a burden that we are obliged to pay forward as immigrants, and as Christians. As a community that has thrived in the spaces opened and enlarged by civil rights struggles, including the current struggles to eliminate racism and white supremacy, we are obliged to pay this forward by making BMA more visible and supporting those that do.

During a Sept. 18, 2020 conference in Rome hosted by the Vatican and the Geneva-based World Council of Churches, Bishop Brian Farrell, secretary of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, declared that Christians have a “moral and prophetic mandate” to seek out “constructive and effective ways to oppose xenophobia [and] racism.”

Pope Francis himself at a weekly address following the killing of George Floyd declared, “we cannot tolerate or turn a blind eye to racism and exclusion in any form and yet claim to defend the sacredness of every human life.” Helping to make BMA visible is a way to practice our faith.

* * *

The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of the Asian Journal, its management, editorial board and staff.

• • •

Enrique de la Cruz is Professor Emeritus of Asian American Studies at Cal State University, Northridge.