People of color, including Filipinos, are less likely to find a stem cell match in national registry

ALAMEDA, CA — In a year marred by crises of varying proportions, everything feels a little bit precarious. Political divisions layered over a global health crisis and the quick erosion of socioeconomic normalities continue to shake the public consciousness.

And just because the COVID-19 remains at the fore of public health doesn’t mean other unfortunate health catastrophes take a backseat.

For a Filipino American family in the Bay Area, the fight for soundness of mind is literally a matter of life and death.

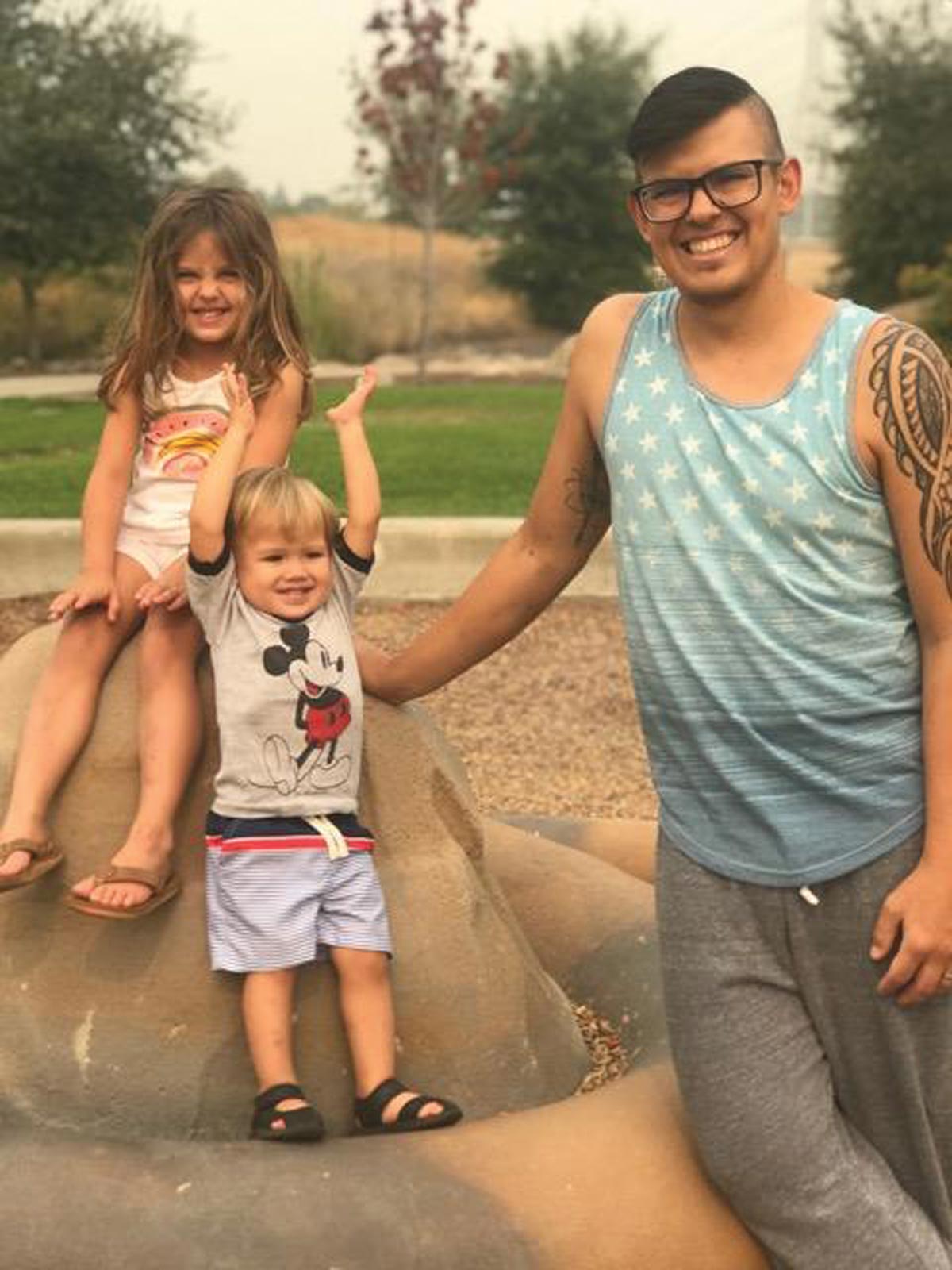

This year, Andrew, a 35-year-old Sacramento-based father of two of Filipino heritage, was diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), a rare pre-leukemia disease, in June and he is in need of a stem cell transplant.

MDS often goes unrecognized and, consequently, is an under-diagnosed group of bone marrow failure disorders. According to the MDS Foundation, between 12,000 and 20,000 new cases are reported every year with patients’ ages ranging from 33 to 55 years old.

Organizations often try to connect patients with stem cell matches, like the Asian American Donor Program (AADP), a non-profit organization based in Northern California that works with a diverse array of blood cancer patients like Andrew to help them find a stem cell match.

“Andrew is dependent on a stranger, most likely Filipino heritage or of Filipino and European heritage, to step forward and register,” AADP Executive Director Carol Gillespie said in a statement, stressing the necessity of more multiethnic donors and donors of color to help close existing ethnic health care gaps.

Andrew is part Filipino with European ancestry, but after it was discovered that his family could not provide a match for him, the family began its search for a stranger who would be a match.

Stem cell matches are based on ethnicity, specifically a patient’s human leukocyte antigen (HLA) tissue type. HLA contains key genetic characteristics and markers that make it possible to undergo a successful transplant. This complicates patients’ of color efforts to find a match and increase their chances of successful recoveries.

The AADP said that people of color who are blood cancer patients are more likely to die from their illnesses than patients of European ancestry who are diagnosed with the same cancers. According to statistics provided to the Asian Journal, the likelihood of finding a matched donor from the national Be The Match registry is 41% for Asians and Pacific Islanders, just above African Americans whose chances are 23%.

“If there’s not enough donors on the registry, then it’s less likely that a patient will find someone with that same genetic marker,” said Mylanah Yolangco, a community engagement representative at AADP.

Yolangco said that potential matches need to be between the ages of 18 and 44 and in “general good health.” Although the age range is wide, the younger the donor, the better the outcome, Yolangco added.

The Be The Match registry — which is operated under the United States Health Resources and Services Administration’s National Marrow Donor Program — says on its website that transplants have higher success rates “when the HLA tissue type of the marrow donor or cord blood closely matches the patient’s.”

It is crucial that patients like Andrew be able to find a match before it’s too late, and his family knows all too well the realities of MDS.

Andrew’s father passed away from the genetic deficiency in 2014, according to a press release, which punctuates the urgency of Andrew’s search for a stem cell match.

The news of Andrew’s diagnosis was a shock to the entire family, especially in a year that was marked by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I guess to put it bluntly, it was like an insult to injury,” Jonah Candelaria, Andrew’s nephew, told the Asian Journal in an interview.

“He’s an amazing father and he’s definitely a family man and he lives life to the fullest, and he loves his daughters and his wife very, very much,” Candelaria said, adding that the COVID-19 pandemic and the safer-at-home orders have made coping with Andrew’s diagnosis doubly difficult.

The distance between Candelaria and his uncle — who haven’t seen each other in person since Christmas of 2019 — has been hard on both nephew and uncle. But because the family is tight-knit, not even the COVID-19 pandemic could dampen the family’s efforts to find a donor for Andrew.

The family has set up a Facebook page to get the word out to potential donors and encourage anybody who may be eligible to request a swab kit.

“Being Filipino, it’s just kind of inherent how we’re just naturally very close and there’s just a lot of love between everyone,” Candelaria said. “So when all this happened, we all kind of came together and did what we needed to do to try to find a donor. There was no hesitation.”

Like nearly every other health care organization, the COVID-19 pandemic shifted daily affairs for the AADP, but the organization is still fully operational, and even those who are not located in the Bay Area could sign up on its website for a swab kit to help patients like Andrew.

For those interested in registering as a potential stem cell donor, visit the AADP website to find out how to receive a home swab kit. Yolangco added that even if potential donors aren’t a match for Andrew, they may be a match for someone else.

“We really want to encourage as many people as we can to sign up,” Yolangco said. “If you think about it it’s kind of like an insurance policy and you never know who will be diagnosed with a blood cancer or disease. It could affect someone in their family down the line, and if we already have people signed up as donors, they’ll be able to find them and get a transplant.”