Architect and professor Edson Cabalfin and Cannes-winning filmmaker Raymond Red discuss cultural identity in post-colonial Philippines

IN 1904, at the World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, the United States’ official exhibition included a live installation of the Philippines, then a U.S. territory.

Just five years before, the 333-year-old occupation by the Spanish Empire of the Philippine Islands ended with Spain ceding the country to the United States. The new colonizers of the Philippines had something to prove.

According to Edson Cabalfin, a Filipino American architect and professor at the University of Cincinnati, the exhibition was less a realistic rendering of the Philippines and Filipinos and more of a public relations move to convince the public that the U.S. needed to maintain control over the primitive archipelago and its “exotic” and “uncivilized” natives.

The installation featured a crude representation of a standard Philippine village that included bahay kubos on lakes, coconut trees and other structures and natural features of the indigenous Filipinos. In addition to physical structures, the U.S. also flew in hundreds of native Filipinos who participated in a stereotypical fashion that many saw as uncivilized: little clothing, prehistoric mannerisms and, most notably, engaging in ritualized consumption of dogs.

“They wanted to show the Philippines as still very primitive and not civilized because that was the only way the American government can justify why they needed to be in the Philippines. Because if they showed it as being civilized, then there would be no need for the U.S. to be in the Philippines. That was the narrative they were trying to showcase,” Cabalfin explained.

From the time of Spanish colonialism to as recent as the late 1990s, this is the way that the Philippines has been portrayed to the world for global exhibitions. This “problematic” representation, as Cabalfin noted, continued even after the Philippines gained independence and speaks volumes of the way Filipinos saw and continue to see themselves.

From the time of Spanish colonialism to as recent as the late 1990s, this is the way that the Philippines has been portrayed to the world for global exhibitions. This “problematic” representation, as Cabalfin noted, continued even after the Philippines gained independence and speaks volumes of the way Filipinos saw and continue to see themselves.

But in the era of diverse representation in the art world, why do some Filipino creatives continue to propagate the antiquated view of the Philippines and, by extension, the Filipino people?

On Wednesday, November 20, Cabalfin joined the Cannes Film Festival-winning alternative filmmaker Raymond Red in a panel called “Artists Talk” hosted by the Philippine Consulate in Los Angeles.

“Artists Talk” is a Consulate series that strives to foster nuanced discussions about Filipino creatives and the role of Filipinos in the art world.

“There is so much potential within our community to really advance creativity in cinema and all arts,” said Red, mentioning the new crop of young filmmakers making a dent in the industry, including his son Mikhail Red whose film “Birdshot” was the first Filipino film released on Netflix worldwide.

But the question still remains about the Philippine image worldwide and the misconceptions propagated by the so-called post-colonial anxiety that has affected creative expression.

“I teach in Cincinnati, and when I show some students contemporary architecture of the Philippines, many of them are surprised we have skyscrapers and all these modern styles of buildings,” Cabalfin shared. “Some of them thought that it was all huts and these very primitive living standards as the norm, even today.”

Along with other Filipino architects, Cabalfin is seeking to change that image of the Philippines. In 2018, at the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale, Cabalfin helmed the committee presenting “The City Who Had Two Navels,” the official Philippine installation which explores the relationship between “the past and the challenges of constructing contemporary subjectivity.”

The pavilion was inspired by the 1961 novel “The Woman Who Had Two Navels” by Nick Joaquin and, at the center of the installation, featured two oval complexes that represent the post-colonial anxiety of the last several decades and how the new wave of “neo-liberalism” affects Philippine urbanity.

Similarly, Red seeks to expand the possibilities of Philippine cinema amid drastic shifts in technology and creative perspective in the cinematic community at large.

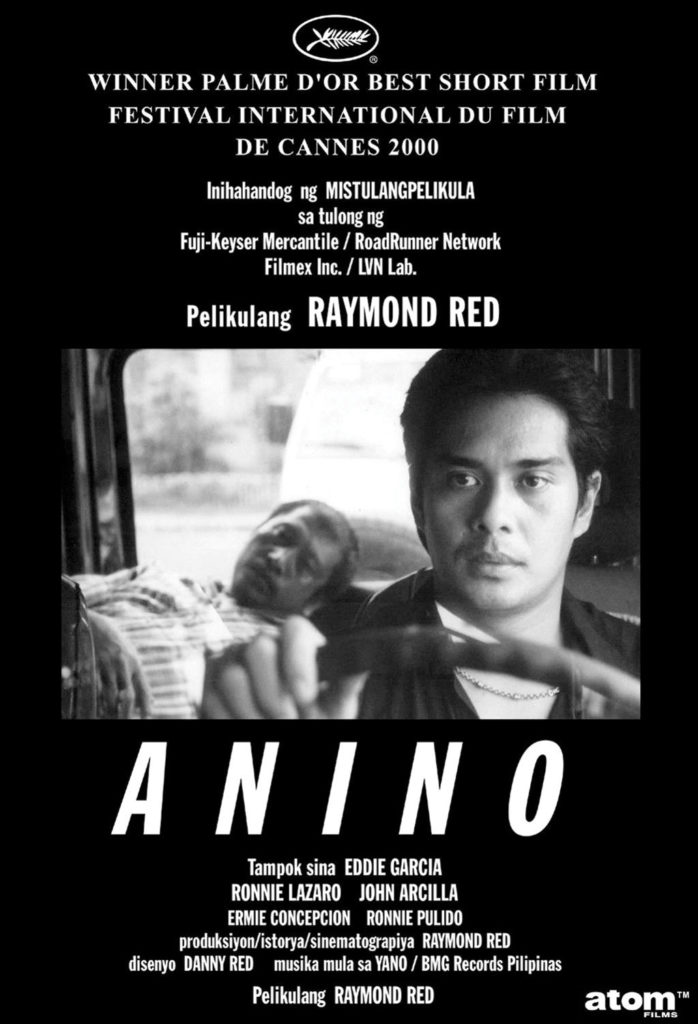

Seen as a pioneer in Philippine experimental film, Red was the first and only Filipino so far to have won the coveted Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 2000 for his short film “Anino.”

The collective with which Red came onto the scene, the small but wily group of experimental filmmakers of the 1980s telling stories through super-8mm and 16mm film cameras, inspired a whole new generation of filmmakers and creatives in the Philippines that seek to change the narrative and take the reins of Philippine representation on a global scale.

“I was a part of the group of young filmmakers who took advantage of the technology that was available to us to be able to create cinema, and the big question back then was, is this legitimate cinema?” Red pondered, showing early examples of moving pictures that are regarded as the pioneers of film as we know it.

He also acknowledged film director and producer Jose Nepomuceno’s role in establishing Philippine cinema in the 1910s. And as the Philippines gained independence in 1946, so did its entertainment industry, paving the way for the Golden Age of Philippine cinema in the 1950s, the second Golden Age in the 1970s and the era of mass-production in the 1980s and 1990s.

But in the case of the 1980s, quality and nuance of cinematic storytelling were sacrificed for national commercial success. Slapstick comedy, melodramas and predictable and hackneyed storylines became cash grabs which, in turn, made them the norm.

Red and the rag-tag group of guerilla filmmakers sought to provide an alternate road for filmmakers, and it wasn’t until the new millennium that independent filmmaking came into the fray.

During 100th anniversary of the establishment of Philippine cinema, there is still concern over the widespread preoccupation of commercial success within the country over international presence and acclaim, but Red assured that the stars are aligned for Philippine cinema to emerge.

“It’s happening now. There are so many ways to get your film made what with the advances in technology and the places and communities where you can share your movies,” Red told the Asian Journal, noting his son’s own success on Netflix. “There’s a lot of rising talent who are innovating the industry nowadays and with the current Film Development Council, there’s a lot of hope for cinema to thrive within our community.”