Gender inequality. Is it an issue some societies in the world have relegated to the past? The trend to recognize same-sex marriages is picking up. Women are accepted (sometimes grudgingly) as equals in areas of employment, world leadership and income generation. It would seem the biological difference between a male or a female are not matters of consideration within the context of equal protection of the law. It is not, however, an absolute rule or as widespread as we wish it to be.

Gender differentiation still matters in drafting laws that are perceived to preserve specific governmental or social “order.” For example, under Philippine law, the mother is given preference over the father in the custody of an illegitimate child below the age of 7, unless she is proven to be unfit. In the United States, immigration rules impose more burden on the U.S. citizen father of an illegitimate child to prove paternity, than on the U.S. citizen-mother to prove the mother-child relationship. In petitioning for an illegitimate child, the U.S. citizen mother only has to show the birth of the child as evidenced by the birth certificate. If it is the father who petitions for his child born out of wedlock (illegitimate), the birth certificate showing acknowledgment of his paternity is not enough. He has to establish proof of his paternity by additional, equally important means. The law provides that “(e)motional and/or financial ties or a genuine concern and interest by the father for the child’s support, instruction, and general welfare must be shown.” (8 CFR 204.2(d) (2) [Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended]). A father petitioning his child to live in the United States must show that he is a father, not just in name but in deed. If it is true that he is the father, he should be able to show that he cares for his child by communicating , being concerned about his/her welfare, sending/giving financial support during those tender years (up to age 18) or if there was an opportunity to live with the child and personally be a parent to the child, then proof such as income tax return records, school and medical/insurance coverage records, may well support the parent-child petition. In cases when the child is born (outside of the U.S.) after the parent is naturalized as a U.S. citizen or when the parent is a natural-born U.S. citizen, the same burden is imposed if the parent is a father. Essentially, the father has to prove his presence in the foreign soil at the time of conception of the child, existing valid relationship with the mother of the child, and acts of acknowledgement of the relationship by the father as the child is growing up. Natural law justifies why these requirements will not be necessary if the U.S. citizen parent is the birth mother. The United States recent history of sending troops to all “corners”of the globe makes it imperative to establish proof of paternity. These deployments gave rise (and continues to give rise) to relationships with foreigners that produce children (remember Ms. Saigon?). Questioning the authenticity of a child’s claim of being a U.S. citizen (as a “G.I.” baby) years after the father goes back to the U.S. with no contact, is legitimate as far as the U.S. government is concerned; hence such additional burden imposed upon the father to prove a valid and legitimate parent-child relationship. Immigration law has recognized these concerns. It is easy to believe and assert that someone is indeed your child; proving such fact is an entirely different ball game.

Adding more requirements for the father to prove a valid parent-child relationship to comply with immigration laws is not a digression from the standards of equal protection of the law nor is it an attempt to assert the primacy of the laws of nature but rather protecting governmental interest from fraud and the untruth.

* * *

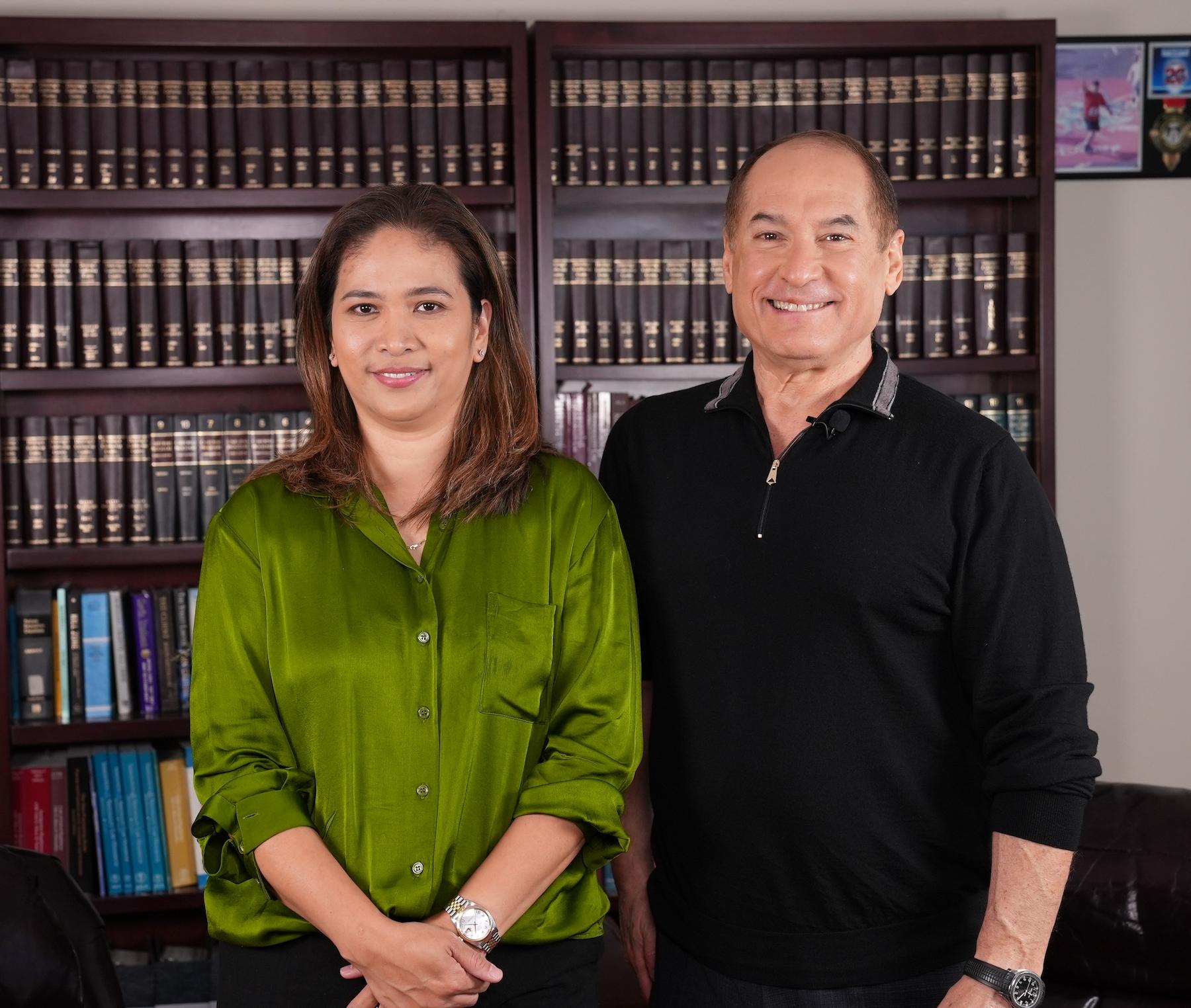

Maria Rita Reyes-Stuby is a licensed attorney in Michigan. She is a graduate of the University of the Philippines College of Law. She specializes in immigration and practices in Las Vegas, Michigan, California and other states. Bernadette Bretana, a graduate of the Ateneo Law School and Ms. Stuby are licensed attorneys in the Philippines. Please call @702-403-4704 or email her at stubylaw@aol.com or go to www.mrstubylaw.com for any questions on this article.