A Filipino sweet soup snack perfect for chilly winter nights

Contributed by Sarahlynn Pablo / Filipino Kitchen

Beyond the brown sugar and coconut milk, my aunt said, any available fruit or vegetable may be used for the Filipino ginataan recipe below, like taro root (gabi), corn (mais), even mongo beans or guava (this last one she said was especially good). The important things are that, like the work of a farm, everyone pitches in — peeling, chopping, dough-ball rolling — to make the dish a sweet success and that the ingredients are local, seasonally available, excess crops.

Eating seasonally and locally makes sense, right? In much of the world, this is the only way to eat. In fact, in America, we are used to eating out-of-season, far away and/or foreign.

When I was growing up in the northwestern suburbs of Chicago, my family was one of a few Filipino families there. For a large part of my childhood, we would drive into the city to Chinatown to stock up on Asian groceries. For Thanksgiving and other holidays, my ninang made lumpia and pancit canton, and little girl me tried to assist her. Of course we had turkey with stuffing and gravy or honey-cured hams, too, but holidays wouldn’t feel special if there wasn’t Filipino food at the table.

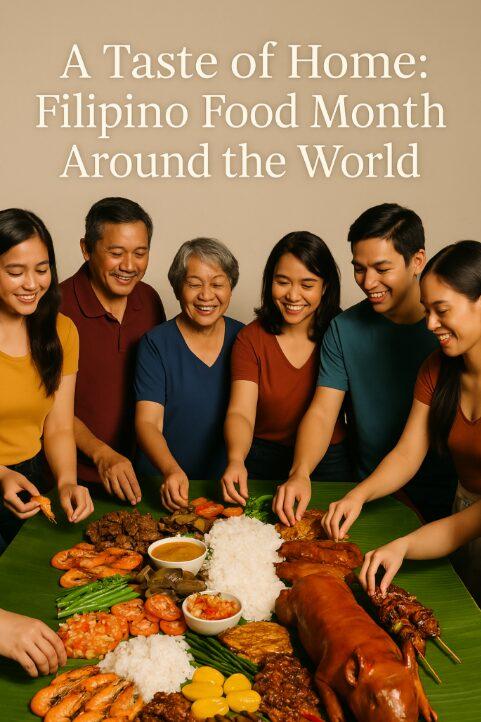

Far from home and surrounded by the unfamiliar, the migrant clings tightly to what she knows best: music, holiday traditions and food. Migrants bring their “stinky” fish sauces and other spices. They pick up from the butcher for free bags full of what would be thrown away and turn it into culinary creations like fish head sinigang or kare-kare with oxtail. They seek out the markets of other, older, more established migrant groups – Chinese, Indian, Mexican – to find ingredients for a taste closer to their own.

Though ginataan calls for seasonal and local, I’m grateful that my family flew in the face of those practicalities / limitations in our little part of America, holiday after holiday, meal after meal.

In the spirit of the cold, Christmas-y season, I’d like to share one of my favorite Filipino late-evening snacks: ginataan bilo-bilo, or coconut milk and rice flour balls – a sweet, hot dessert-y soup perfect for when the mercury dips low.

My aunt reminds me that this dish is actually a snack, or merienda. Though sweet, ginataan is too heavy to serve as a dessert at the end of a meal. Merienda, I should note, is a very important part of agricultural life in the Philippines.

Life on a farm, day into day and months into seasons, is a dance. It has a rhythm.

In the couple of hours after lunch, it’s much, much too hot for the workers, the kids, the farmers to do strenuous physical activity in the sun. You look to do some activity that’s still necessary to make the farm run but doesn’t require a lot. Maybe you’d take a short siesta (nap). Bring the goats out to the field. Thrush some rice. Make feed for the pigs. Dress some tobacco leaves. Or maybe you could take on a few of those things. After a few hours of low-key activity, you need merienda before the hard work begins in earnest again at 3 o’clock. Enter ginataan.

Ingredients

Milk and meat from two coconuts (gata). This is the critical ingredient.

Brown sugar. The second of two critical ingredients.

Six plantains or cooking bananas, peeled (saba)

Ten pieces of jackfruit, pitted (langka)

Grated cassava root (kamoteng kahoy), two medium-sized pieces

Glutinous rice flour (malagkit), two cups, and water for bilo-bilo. Yep, literally, that’s ball-ball.

One medium sweet potato, peeled (kamote)

Three small purple yam, peeled (ube). If you add this, obviously, your ginataan will have a tingle of violet.

Two notes on ingredients. One: Where available and possible, fresh ingredients are best. Most of these ingredients may be available in canned or frozen form in non-tropical climes where there are communities of Asians or Filipinos nearby. Substitute canned or frozen counterparts if you need to and don’t feel any shame about it.

Two: I’ve added suggested amounts of each ingredient but suit the proportions to your taste. If you like more cassava root like I do, add more of those. If you’re on a low-sugar diet, put less.

Instructions

1. Open the coconuts carefully and set aside the milk. Scrape the meat from the husk into strips. Or you can just buy fresh scraped coconut meat and fresh coconut milk if you don’t have the tools (we did). Squeeze the remaining milk from the coconut flesh with your bare hands or with a cheese cloth. Simmer the coconut milk in a large pot with brown sugar. Make sure the brown sugar is fully dissolved.

The brown sugar pictured is unrefined, wrapped in a leaf and formed in a coconut shape called panutsa (also known by panotcha or panotsa, which are also the words for peanut brittle). It was so tasty, I think, owing to its smoky molasses quality. I was lucky enough to have shared some with my cousin in the Netherlands in the ginataan she made. She used about a third of this half-dome of sugar. If you’re not lucky enough to get this awesome sugar, granular brown sugar works just fine, too.

2. Now, the remaining ingredients – plantains, jackfruit, cassava, rice flour balls, sweet potato, purple yam – need to be cut or formed at approximately the same size, I’d say half-inch to one inch pieces, so each spoonful has a few small bits of awesome. All the kids are going into the coconut milk pool later.

3. Glutinous rice flour bilo-bilo. Put a cup of the flour in a bowl, add water slowly, a spoonful at a time, stirring slowly. What you want to form from the flour and water is a paste that holds its own. You can tell when it’s “done” when the paste will come up off the bottom of the bowl cleanly when you scrape it with a spoon. After you get the paste to this point, let it rest for a few minutes on the counter. This paste is called galapong, the sticky rice flour dough that is the basis for an infinite number of kakanin, rice-based desserts like bibingka. Get a plate and sprinkle it with rice flour. Pick up a little divet of that flour with your fingers and rub it around your palms. Snip off a bit of the dough paste, and form it into a ball by rolling between your floured palms. Set the little ball on the floured plate. Repeat.

4. Cassava root. If using fresh cassava, cut a narrow, diagonal line the length of the root. This will help you shave off the root’s bark. Grate the root, though at the core of the root is a very stringy and tough core. Don’t include that. The core left will be about as wide as your pinky finger. Squeeze out the water from the grated cassava root with your bare hands or with a cheese cloth.

Form the grated root into balls. Add a little of the glutinous rice flour to help it stick together. These cassava truffles – if I may coin this phrase – are really delicate.

Pictured here is frozen, packaged cassava. Defrost and treat it the same as the fresh root.

4. Now that the sugar’s all dissolved in the coconut milk, layer your cut-up ingredients inside, with the heavier, denser ingredients going in first: sweet potato, purple yam, jackfruit, glutinous rice balls and cassava root truffles. Once you’ve layered everything inside, DON’T STIR THE POT. The cassava’s really delicate (just reminding you!) and, with all that starch, stirring too much will make the ginataan too thick. Just let everything get warm, and come up to a simmer.

Get a hot bowl and a spoon and go to town. Sweet, stick-to-your-ribs, warming taste of home.

* * *

Sarahlynn Pablo is the co-founder of Filipino Kitchen, a food media and events group whose mission is to connect Filipinos across the diaspora with their culture and history by celebrating our cuisine. With fellow co-founder, Natalia Roxas, they produce the annual Kultura Festival in October. Pablo, 38, lives in and loves Chicago. For more stories and recipes, please visit http://filipino.kitchen.