THE first day of filing for Certificates of Candidacy (COCs) at the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) may have been rambunctious enough for COMELEC Chairman Sixto Brillantes to deem it “a circus.”

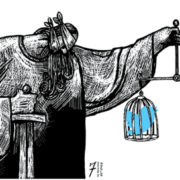

Yet, it pales in comparison to the decibels raised (and are still being raised) by outraged netizens over some controversial provisions in the enacted Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 or Republic Act 10175, which was signed by Pres. Benigno Aquino III on September 12 (only a few days before the 40th anniversary of the Declaration of Martial Law) and became effective on October 3.

Black Tuesday overpowered the flurry and festivity of political colors on Monday, as various groups marched to the Supreme Court to protest against “Cyber Martial Law.”

Clad in black shirts and “gagged” with black adhesive tape while flashing black placards, the protesters signified the breach of the constitutional right to freedom of speech.

The Supreme Court has postponed any action on pending petitions (seeking to junk certain provisions from the Cybercrime law) until October 9.

The internet was just as equally inundated by remonstrations by fearless netizens, who dissent from the cybercrime law. Facebook users intentionally “blacked out” their profile photos, posts and comments (labeled as “COMMENT BLOCKED. RA NO. 10175”) and circulated photos, memes and images to emphasize their outrage over the new law.

Some even joked that they will see each other in jail, because of the posts and comments they made.

A petition filed by UP College of Law professor, Harry Roque Jr. (along with bloggers, journalists and lawyers) points out the unconstitutionality of 5 specific provisions in RA 10175, namely Sections 4,5,6,7 and 19.

Senator Teofista Guingona III (who was against the bill from the very beginning and who also filed a petition to the Supreme Court) said that RA 10175 “demonizes technology,” and also opined that the provisions are “an assault against our fundamental constitutional rights and throw us back to the dark ages.”

Section 1 of the Bill of Rights in the 1987 Philippine Constitution states that: “No person shall be deprived of life, liberty, and property without due process of the law.”

Section 4 of the Bill of Rights states that: “No law shall be passed abridging the freedom of speech, of expression, or of the press, or the right of the people to peaceably assemble and petition the government for redress of grievances.”

On Wednesday, Justice Secretary Leila De Lima told members of the Philippine media that there is nothing unconstitutional about the law, based on what she has read so far. She also assured the public that the Department of Justice will “thoroughly study the law and take into consideration feedbacks from various agencies in crafting and implementing rules and regulations (IRR),” as reported by Inquirer.net.

De Lima further added that the DOJ will “determine how the IRR can be used in terms of clarifying, harmonizing those objectionable portions.”

Malacañang (through presidential spokesman Edwin Lacierda) has called for a “responsible discourse” between concerned stakeholders and the DOJ on the Cybercrime law and has assured that the Palace “recognizes and respects efforts not only to raise these issues in court, but to propose amendments to the law, in accordance with constitutional processes.”

“We have not stopped anyone from expressing their concerns. And we have also stated for the record and in my statement that we respect efforts (to challenge the law),” Lacierda said.

“Our Constitution is clear and uncompromising in the civil liberties it guarantees all our people. As the basic law, its guarantees cannot, and will not, be diminished or reduced by any law passed by Congress,” Lacierda further added.

In defense of PNoy, Lacierda said that the President cannot really veto some lines “unless it is an appropriations bill such as budget.”

“So if it’s an appropriations bill you can veto a line-item. You cannot do that in a non-appropriations bill. You either sign the entire law or you veto the entire law,” Lacierda said. “We will work within the tenets of the ambit of the Constitution. That is our guarantee to all the people.”

Admitting that RA 10175 is “not a perfect law,” Lacierda said that Malacañang’s communications team might participate in Tuesday’s crafting of the IRR at the DOJ and “might even suggest their own amendments to the law.”

Lacierda also clarified that the IRR would not be enough to correct the errors because “the water cannot rise above the source.”

However, PNoy said that he does not agree “that the provision on online should be removed. Whatever the format is, if it is libelous, then there should be some form of redress available to the victims,” the Chief Executive said in an interview on Friday, amid opposition from legal experts, who asserted that including libel in the cybercrime law would “be tantamount to double jeopardy,” reports InterAksyon.com.

Meanwhile, Sen.Chiz Escudero (who is up for re-election and is one of those responsible for the passing of the bill) admitted that there was an oversight on his part, when he voted for the passage of the bill. He recently filed Senate Bill No. 3288 with an explanatory note stating: “This bill repeals Section 4 (c) (4) of Republic Act No. 10175 or the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012, finding basis on the unequivocal constitutional provision on freedom of speech. It is submitted that any form of libel is a form of ‘abridging the freedom of speech, of expression, of press.’”

Senators Pia Cayetano, Antonio Trillanes IV, Koko Pimentel and most importantly, the author of the bill himself, Sen. Edgardo Angara, have also followed suit. Angara said that he will file an amendatory bill “to include the principle of search and seizure order under the Constitution.”

This bold admittance of errors in lawmaking by senators and by Malacañang only highlights the contrast in juxtaposition: political colors may change, but the unified tone of a disgruntled public is still king, in a democracy.

Undoubtedly, despite the dark side of cyberspace (i.e. blatant cybercrimes), the internet has become an indispensable means to measure public opinion. Beyond trolling, cyberbullying and scathing commentaries and blogs, the internet is now the new medium of choice for intelligent discourse.

To deprive 29 million social media users/potential voters of this newfound freedom, at this juncture, would carry dire consequences.

Even the United Nations has declared internet freedom as a basic human right: “The same rights that people have offline must also be protected online, in particular freedom of expression, which is applicable regardless of frontiers and through any media of one’s choice.”

The UN also calls upon leaders “to promote and facilitate access to the internet” and recognizes “the global and open nature of the internet as a driving force in accelerating progress towards development in various forms.”

(AJPress)