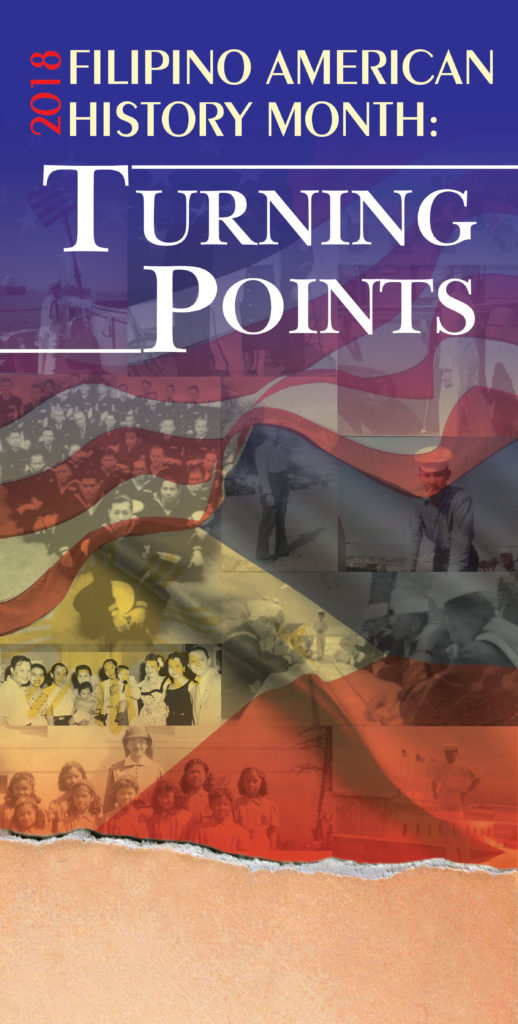

This October, honoring Fil-Am ‘Turning Points’ and the successes they empowered

IN the United States, October is Filipino-American History Month, and it is just what the title denotes: looking back at the historical achievements and milestones of the Filipino-American experience as it relates to American history.

This year marks the ninth Filipino-American History Month since the U.S. Congress officially recognized it in 2009.

The Filipino American National History Society (FANHS) has chosen the 2018 Fil-Am History Month theme to be “Turning Points” in honor of the three biggest events that changed the lives of Filipinos and Fil-Ams: the declaration of the Philippine independence and the establishment of the First Philippine Republic, the Spanish American Way, and the establishment of Ethnic Studies in the states.

The Filipino American National History Society (FANHS) has chosen the 2018 Fil-Am History Month theme to be “Turning Points” in honor of the three biggest events that changed the lives of Filipinos and Fil-Ams: the declaration of the Philippine independence and the establishment of the First Philippine Republic, the Spanish American Way, and the establishment of Ethnic Studies in the states.

In 1988, the FANHS designated October to celebrate Filipino-American history in honor of the first Filipinos to arrive to North America on Oct. 18, 1587 in California.

This year in particular marks the 120th anniversary of the declaration of Philippines independence from Spain in 1898, and by relation, the 120th Anniversary of the Spanish-American War. On June 12, 1898, Emilio Aguinaldo, the leader of the Philippine Revolutionary forces, declared Philippines’ independence from Spain, and established the First Philippine Republic.

But as many Filipinos know, the freedom was short lived as the Philippines was then given to the U.S. as part of the 1989 Treaty of Paris Agreement. The Philippines, thus became a U.S. territory with the Philippine-American War rising up a year after.

Although the month of celebration has mistakenly been called “Filipino American Heritage Month,” it goes without saying that celebrating the very specific history of Filipino-Americans, the centuries-long emotional rollercoaster, elicits a certain brand of cultural pride throughout the community.

FANHS has cited in the past that, rather than heritage, the month should focus on history, i.e. dated events, experiences and the lives of the people who impacted the community, rather than elements and traditions that cultivate cultural pride.

Filling gaps in history lessons

Filipinos today make up the third largest Asian American group in the entire United States with nearly four million Filipino-Americans in the country, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s latest American Community Survey (ACS) data.

Narrowing the scope, Filipinos have become the largest Asian group in 11 states being Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Washington, Wyoming, and South Dakota.

With a demographic impact such as that, it’s no wonder there’s a whole month celebrating the history of Filipinos in America. For more than a hundred years, Filipino-Americans have been making strides to cement the Filipino-American identity within the overall American experience.

Like many minority groups’ lived experiences in America, the history of the Filipino-American is intricate and ample, but, often, neglected and overlooked; Filipinos are rarely mentioned in school textbooks across the U.S. But its non-existence in textbooks doesn’t negate the formidable impact Filipinos have made in the fabric of American history.

Many of us who grew up in the American school system didn’t learn much (if at all) about the colonization of the Philippines by America at the turn of the century.

Filipinos were the first undocumented Asians to arrive to the continental United States in 1587, 33 years before European Pilgrims touched down at Plymouth Rock and 200 years before the founding of the U.S.

In the mid-1500s, Spain began its conquest to officially colonize the Philippines, which led to the Manila galleon trade that sailed from Cebu, Philippines (and later, Manila) to Acapulco, Mexico. During one voyage from the motherland, a galleon containing Spaniards and Filipinos — called by the Spaniards Indios Luzones — touched down into what is now known as Morro Bay, California.

It wasn’t until the late 1800s that the first Filipino was naturalized as an American citizen, Ramon Reyes Lala, a London-educated writer from a wealthy, upper-class family.

The first major wave of Filipino migrants came during the period when the Philippines became a U.S. territory from 1898 to 1946, when the country gained independence.

We didn’t learn about prolific Filipino-American writer and poet Carlos Bulosan who once said, “We…recognize the forces which have been trying to falsify American history—the forces which drive away many Americans to a corner of compromise with those who would distort the ideals of men that died for freedom.”

We certainly didn’t get a just account of the Filipino war effort in World War II, and how that shaped the profound stake Filipinos have in the U.S. Armed Forces that persists today.

During this time, Filipinos lent their services to the U.S. Armed Forces during World War II in which more than a quarter million Filipinos responded to then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s call-to-arms.

For decades, these brave men and women who fought under the American flag would not get the recognition they deserved until the Obama administration, which began offering benefits to the surviving Filipino WWII Veterans and their families.

In 2017, these brave veterans and their families received the Congressional Gold Medal to commemorate their powerful, yet forgotten efforts in the war.

Even Itliong, along with fellow Filipino-American labor leader Philip Vera Cruz, has been often relegated to a footnote of classroom lessons about the Delano grape strike, often overshadowed by his Mexican-American counterpart Cesar Chavez.

But that is slowly changing as public schools are slowly incorporating more Filipino-American history curricula. CA Assemblymember Rob Bonta, a Filipino-American, introduced legislation that would include the role of Filipinos in the labor movement in California.

“It’s about time,” Johnny Itliong, Larry’s son, said after Gov. Jerry Brown signed the bill into law in 2013. “I’ve waited most of my life for people to give my father credit for his work. This is a dream come true.”

Fast forward over a century later through years of Filipinos creating their lives in the U.S., this year also marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of a number of Filipino ethnic studies programs in U.S. universities such as San Francisco State University, UC Berkeley, and UC Davis.

Just a couple days before Fil-Am History Month commenced, UC Davis launched the pioneering Bulosan Center for Filipino Studies — named after Filipino author and activist Carlos Bulosan — which is believed to be the first of its kind not only in the University of California system, but in the nation.

Empowered success

In 2008, the State of Hawaii became the first state to officially observe Filipino-American History Month in October. California followed in 2009 when the State Legislature passed a resolution officially recognizing the month-long celebration.

In 2016, former U.S. President Barack Obama said during a White House celebration of Fil-Am History Month, “Filipino-Americans have long played an integral role in shaping the life of our country. They have been the artists who challenge us, the educators who keep us informed, and the laborers of our growing economy.”

“Their immeasurable contributions to our Nation reaffirm that as Americans, we will always be bound to each other in common purpose and by our shared hopes for the future,” he added.

Through the turning point events and the struggles of the previous generations of Filipinos, Filipinos in the following years have found a way to not only thrive and become a part of the U.S. identity, but be contributors to it.

These Fil-Ams include Pedro Flores, a Ilocos Norte native, who spent the years between 1929 and 1932, inventing and popularizing yo-yos while living in Santa Barbara, California.

A few years later in 1936, another Filipino was making waves on the nation’s east coast.

Manila-born Fe del Mundo not only became the first Filipino, but the first Asian and first female to ever attend Harvard Medical University. While del Mundo was accepted into the program under the administrator’s mistake of her gender, she was able to keep her enrollment because of her strong records. She of course also found success back home as the first woman to ever be named the National Scientist of the Philippines in 1980. She also founded the first pediatric hospital in the Philippines.

When it comes to music, Filipinos to this day continue to find ways to shine in the music industry. In the 1950’s, half-Filipina singer Sugar Pie DeSanto (Umpeylia Marsema Balinton) found success as a R&B singer with many songs landing on the Billboard’s Hot R&B chart. Giving her the name Sugar Pie was none other than the famous American musician Johnny Otis.

In the world of social activism and civil rights, there were of course Larry Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz, Fil-Am farm workers who most notably pioneered the 1965 Grape Strike and Boycott and were leading voices in the agricultural strikes throughout Central and Southern California.

Entering the early 2000s, Fil-Ams saw the successes of creatives like Philippine-born animator Van Partible, who animated and created the classic Cartoon Network series Johnny Bravo; and Cristeta “Cris” Comerford who at the age of 21, moved to the U.S. where she ended up becoming the first Asian and first ever female White House Executive Chef, a position she still holds since starting over 10 years ago.

And then there’s Fil-Am historian, activist, and professor Dr. Dawn Mabalon who inspired many of today’s young Fil-Am generation through her writings, teachings, and enthusiasm for Fil-Am histories and experiences.

The FANHS has this year dedicated this year’s Fil-Am History Month to be in memory of Dr. Mabalon, who suddenly passed away in August while on vacation in Hawaii.

“Collecting, preserving, and spreading knowledge about Filipino American history for our community was an honest and vibrant labor of love for Dr. Dawn Mabalon,” wrote the FANHS.

“As she noted, ‘History is about the events, experiences and lives of people in our community (in the U.S.) and their impact upon society and the political, cultural and economic events and moments that shape their lives,’” the FANHS quoted Mabalon once saying.

As we celebrate Fil-Am History Month, let us not forget the turning points, the people those events involved, and the opportunities they provided us in the following years.

History is an ongoing account of the human experience as it relates to social and political change, and Filipino-American history continues to manifest itself as a story of continued resilience and respect; it’s a book with no conclusion, a sentence without a conclusion.

We all play a part in the history of the Filipino-American, and the reckoning of immigrant rights, intersectional feminism and representation of Filipinos in public roles is currently being written and will be written in our history. Understanding the history of Filipino-Americans helps us understand how we got here and gives us an idea of what we’re capable of in the present and future.